Extract: 'Til Death Us Do Part' - Dickens's first biographer | reviews, news & interviews

Extract: 'Til Death Us Do Part' - Dickens's first biographer

Extract: 'Til Death Us Do Part' - Dickens's first biographer

Claire Tomalin is Dickens's latest biographer. Here she describes how he befriended his first, John Forster

Over their lifelong friendship Dickens sometimes mocked Forster and quarrelled furiously with him, but he was the only man to whom he confided his most private experiences and feelings, and he never ceased to trust him and rely on him. It was not a perfectly equal friendship, and Dickens sometimes took Forster for granted, and went through periods of coolness towards him, turning to another friend for a time; but when he was in real need of help it was always Forster to whom he went.

They were always at ease with one another, with no need to pose or pretend, and much in common. Each knew that the other had started with few advantages, from poor and undistinguished family backgrounds, and had a struggle to establish himself in a society in which money, rank and patronage often seemed to count for more than talent. Both had shown early promise and put in long, hard hours of work in order to make their way in the world against the odds.

Pleasure apart, Forster’s arrival in Dickens’s life changed it profoundly

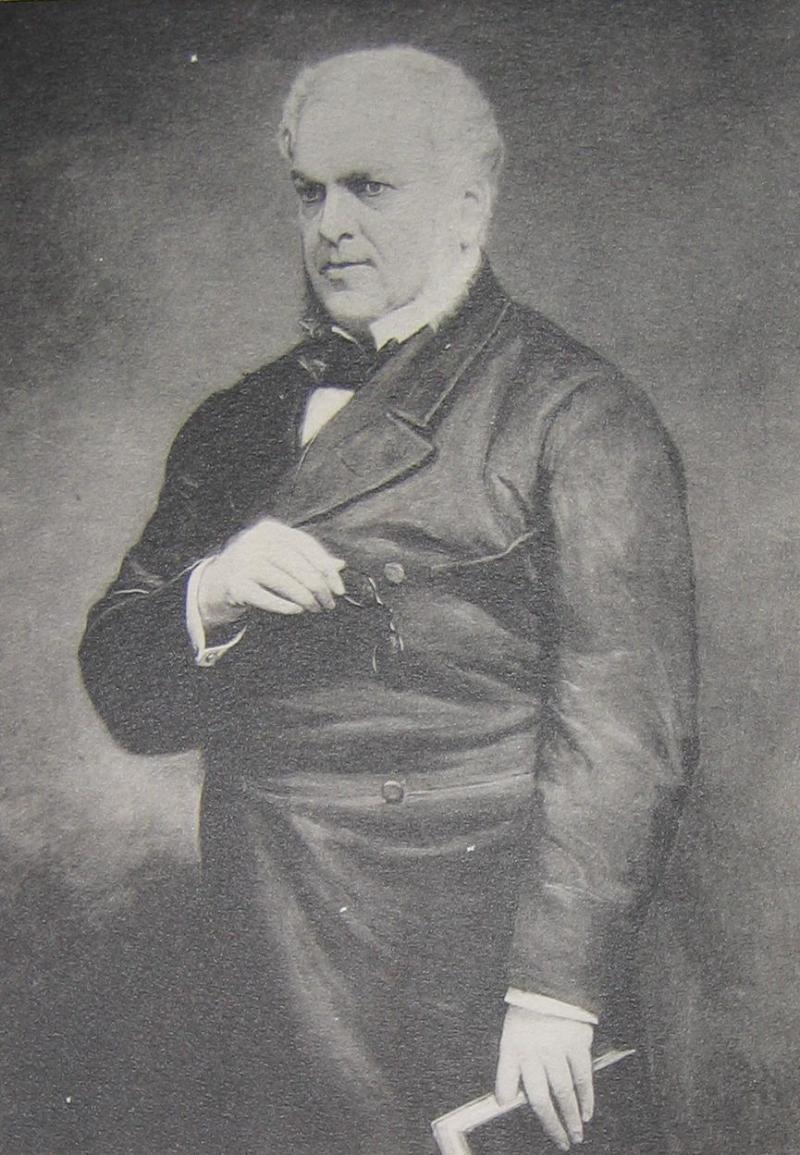

Forster had first noticed Dickens when he joined the True Sun in 1831 as drama critic, and saw one day, standing on the staircase at the office, ‘a young man of my own age whose keen animation of look would have arrested attention anywhere, and whose name, upon enquiry, I then heard for the first time’. No words were exchanged, but Forster kept this bright image in his mind.

In 1835 Forster became the literary editor of the Examiner, and by the time he got to know Dickens he was a respected critic and becoming an influential figure in the London literary world. Dickens was a rising star whom Forster believed to be a genius, and was ready to serve that genius, while Dickens realized Forster could be an invaluable adviser and supporter. Each had something to gain from the friendship, but what counted still more was the strong spontaneous personal affection that rose up between them.

Among Dickens’s surviving letters, there are a great many summoning Forster to ride with him or to come round and simply be with him: "My Missis is going out today, and I want you to take some cold lamb and a bit of fish with me, alone. We can walk out both before and afterwards but I must dine at home on account of the Pickwick proofs." "I ought to dine in Bloomsbury Square tomorrow, but as I would much rather go with you for a ride... that’s off... So engage the Osses." "You don’t feel disposed, do you, to muffle yourself up, and start off with me for a good brisk walk over Hampstead Heath?" And so on.

Pleasure apart, Forster’s arrival in Dickens’s life changed it profoundly. He began immediately to ask Forster for advice and practical help in dealing with his publishers. And from the late 1830s on he acted as Dickens’s "right hand and cool shrewd head". With his good business sense and stubbornness, he proved an extremely effective negotiator. He read all his proofs, correcting and cutting when asked, and from 1838, as he recalled, "There was nothing written by him... which I did not see before the world did, either in manuscript or proof." Unlike a modern literary agent, he also felt free to review Dickens’s books.

Dickens wrote at once to thank him: "I feel your rich, deep appreciation of my intent and meaning more than the most glowing abstract praise that could possibly be lavished upon me. You know I have ever done so, for it was your feeling for me and mine for you that first brought us together, and I hope will keep us so, till death do us part. Your notices make me grateful but very proud; so have a care of them, or you will turn my head." Everyone is grateful for a good review, but the tone of Dickens’s thanks is more than grateful, with its allusion to the marriage vow. They had been getting to know each other for only a few weeks, and this reads like a love letter. When Dickens returned from six months’ absence in America, in July 1842, he drove to Lincoln’s Inn and, finding no one at home, guessed where Forster might be dining, told his driver to take him there and sent in a message to say that "a gentleman wanted to speak to Mr Forster". Dickens’s own account of what happened next says everything about the intensity of his friend’s feelings. Guessing it was Dickens, Forster came flying out of the house without stopping to pick up his hat, got into the carriage, pulled up the window and began to cry.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review – compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit Farm Hall

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review – compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit Farm Hall

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Add comment