Interview: Novelist Gillian Slovo | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: Novelist Gillian Slovo

Interview: Novelist Gillian Slovo

The South African novelist who wrote of The Riots tells of the forces which shaped her career

“To my friend Craig.” As all writers must, Gillian Slovo will put her signature to copies of her 2008 novel, Black Orchids, for queues of readers. No other writer will have performed this promotional ritual, only subsequently to discover, as Slovo did, that she had signed a book to the man who murdered her mother.

Slovo’s latest play, The Riots, which has won wide acclaim, followed on from her previous commission for the Tricycle Theatre in north London, Guantánamo: Honor Bound to Defend Freedom, which she wrote with Victoria Brittan. But she is principally a novelist for our times whose abiding subjects are displacement and the presence of the past. Her formative years were spent in Johannesburg where her communist parents – Joe Slovo and Ruth First - were among the very few whites to take up the struggle against apartheid. The year the ANC leadership was rounded up and imprisoned, Slovo was wrenched into exile. For the past 48 years she has lived in London. Not that you’d necessarily know it from her fiction. The novel she signed to Craig Williamson, a former henchman of the South African security apparatus, was like many of her books fixated on the place she came from. The twisted probability is that she has Williamson’s deed to thank for the burgeoning of her fiction.

I spent a lot of my childhood eavesdropping and trying to work out what was going on

“I might never have written my first novel if it hadn’t been for my mother’s murder,” she concedes. “Up till then, the crime stories I was writing were set in north London where I lived.” We are in her north-London flat. At 59, Slovo is now beyond her mother’s age at her death. For all her early efforts to suppress it, the long anglicised daughter’s voice still has the unmistakable clip of southern Africa. “South Africa had caused me a considerable amount of pain. I just wanted to leave it behind. But my mother’s murder told me how foolish this project was.”

Ruth First was killed by a letter bomb in Mozambique in 1982. Her murder had the same catalytic effect on Slovo’s older sister Shawn, who duly wrote the screenplay for A World Apart (1988) about her mother’s imprisonment without charge in 1963. Gillian, the middle daughter, suspended crime-solving in Hackney to set Ties of Blood (1989) in the milieu of ANC activism. Subsequent novels stayed in and around her South African experiences as the country emerged into democracy.

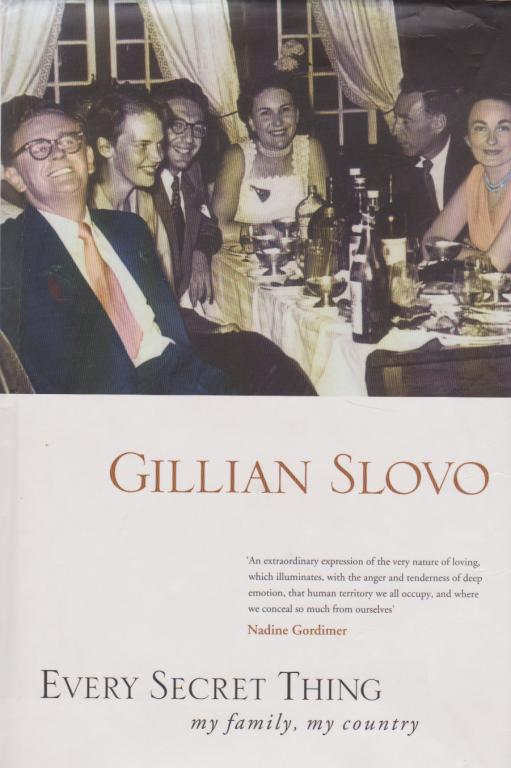

Then, in 1997, Slovo published a heartrending memoir entitled Every Secret Thing: My Family, My Country. It began by describing a childhood defined by the negligence of parents who were committed to a higher cause, and concluded with the moment she courageously interviewed Williamson.

Then, in 1997, Slovo published a heartrending memoir entitled Every Secret Thing: My Family, My Country. It began by describing a childhood defined by the negligence of parents who were committed to a higher cause, and concluded with the moment she courageously interviewed Williamson.

“I didn’t really think about how hard it was. In fact I found it easier to interview that man waiting to hear what he had done than I did to sit opposite him in the Truth Commission when I already knew.” Stimulated by the imperfections of the political amnesty which got men like Williamson off the hook, Red Dust (2000) scratched the South African itch one last time with a forensic examination of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s impact on its participants. Whereafter Ice Road (2004) set up epic residence in Leningrad under siege. It is almost as if she selected the subject blindfolded.

“I just went to the library to see if it would interest me, and it did.” Black Orchids begins in the equally unfamiliar territory of Ceylon (which by the book’s conclusion has become Sri Lanka) then fetches up in London in the Sixties, much as Slovo did as a young woman.

“The Sixties changed the idea of what is a good character and what makes a character,” she says. What makes a character was not something that initially exercised Slovo as a writer. Moving away from journalism, she latched onto crime fiction because “the plot made me feel safe. I didn’t quite understand how you explore character”. Amazingly she carried on describing fictional corpses in her crime novels even after she endured the task of visualising in words the sight of her mother’s immaculately shod legs jutting out from under rubble caused by the bomb. That she stuck to a life of crime writing for two further novels suggests that, as in all her work, even her pot-boilers were deeply connected to the childhood anxieties she describes in Every Secret Thing.

“Because of what my parents were doing in South Africa, a lot of it was secret and felt dangerous, so I spent a lot of my childhood eavesdropping and trying to work out what was going on. And in hindsight that is what a detective does: trying to find out what other people are keeping from them.”

“Because of what my parents were doing in South Africa, a lot of it was secret and felt dangerous, so I spent a lot of my childhood eavesdropping and trying to work out what was going on. And in hindsight that is what a detective does: trying to find out what other people are keeping from them.”

The novels she went on to write seem to have been a form of private Truth and Reconciliation Commission in which, through examining the forces which governed their decisions and impacted on their daughters, Slovo came to grant them a kind of amnesty. Even if it had given her nothing to write about, does she ever wish they had done less?

“I certainly did use to. I don’t really feel like that any more, partly because it isn’t difficult any more and partly because they gave us a wonderful gift. We don’t have to think, did we do enough? They did it for us.” Having left her homeland without a passport, Slovo returned there to live for nine months in the mid-1990s. She got a family memoir out of it, but the temptation to sink roots back into the red dust was finally resisted.

“It was the most exciting time of any to be in a country and I thought if I stayed I wanted to be part of that. But writing is such an isolated activity, I would not have felt properly part of South Africa. I don’t know if that was right. But I did have a sense of belonging. If I look at the southern hemisphere sky, to me that feels what a sky should look like.”

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Bach’s B minor Mass, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin - everything human and divine

Perfect ensemble runs the gamut of a supreme masterpiece

Bach’s B minor Mass, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin - everything human and divine

Perfect ensemble runs the gamut of a supreme masterpiece

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Add comment