Q&A Special: The Late Merce Cunningham | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A Special: The Late Merce Cunningham

Q&A Special: The Late Merce Cunningham

The great dance radical fields questions from eight choreographers

Tonight the company dedicated to the greatest radical of modern dance, Merce Cunningham, opens its farewell tour to London, a valedictory odyssey that will end next year. Last year Cunningham died, aged 90. He had just premiered a work called Nearly Ninety, and this is fittingly the last thing we will see of his company as it blazes one final circuit before closing down in December 2011.

Few cities had taken him more to heart than London, where despite the public's unbudgeable love of story, ballet and musicality in dance, such a fast spiritual kinship evolved between them and the American that fleets of British choreographers cited him above all as their inspiration. And the older he got, the more the younger dancemakers were attracted to his constantly stimulating ideas, mischievously disconnected from theatrical norms, always purely abstract, always randomly constructed, and yet always so exquisitely refined that some people secretly thought of it as an ethereal version of ballet.

It was in that light that when in 2004 I went to New York to meet him to find out for the Daily Telegraph about yet another fiendish new demonstration of his love of chance collisions between music, art and dance, I decided to make my interview a random selection of questions posed by leading choreographers from over here. Cunningham’s ageless curiosity was clear from his newest work, Split Sides, involving music from leading young bands Sigur Rós and Radiohead, but as always the elements working together would be chosen by the rolling of I Ching dice - a belief in the aesthetic virtues of chance that Cunningham made the raison d'être of more than 60 years of unflagging creativity.

He died in July last year, three months after premiering Nearly Ninety on his 90th birthday - 67 years after his first dance concert in 1942 when he and John Cage first worked together. He made more than 200 danceworks. Some 50 are being prepared as research "capsules" to enable them to be performed by other companies (such as Rambert, currently showing Rainforest this season), but after this tour Cunningham's works will depend on the kindness of strangers, and will become gorgeous, enigmatic, otherworldly museum pieces.

ISMENE BROWN: I saw Split Sides in Bergen - you had Norwegian royalty there!

ISMENE BROWN: I saw Split Sides in Bergen - you had Norwegian royalty there!

MERCE CUNNINGHAM: Yes. Their majesties. I knew they were there in one form or another! Heh-heh-heh!

You show a lot of your working methods in Split Sides.

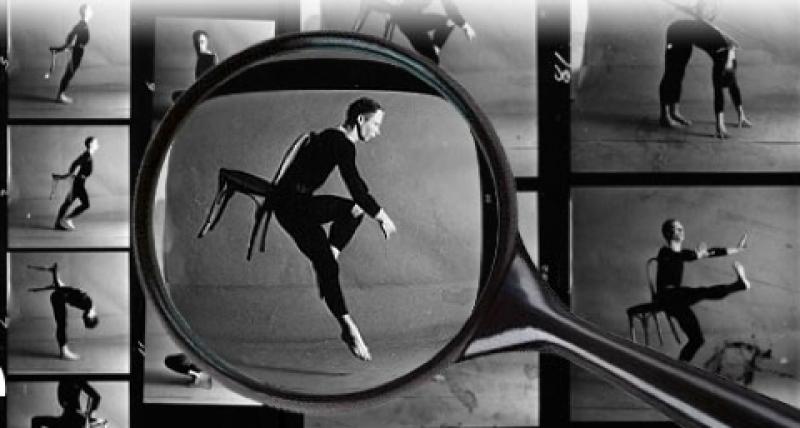

Well, some of it, yes. (Cunningham pictured by Annie Leibowitz for MCDC)

It's like you're splitting on yourself.

[Laughs.] The title is to indicate the possible shifting of things, having more than one side. And the introduction of the chance procedure into the daily performance, we toss the coin at each rehearsal to see whether we do A or B first.

Do you allow yourself to prefer it one way or the other?

No. [Decisively and instantly.] No.

Do you notice if they forget something, is it very obvious?

Oh yes. Oh always, yes.

Do you remember every single step you make?

No, good heavens, no. But I remember a lot of it. And the dancers are very good about it - if something goes off when you are rehearsing, I make a little note to myself when I'm watching, so I can remember to ask. Usually they've already figured it out, and the minute it's over they go over to the tape to check what happened. I'm sure that's true of every company - how would you keep track otherwise?

After the performance I jumped into the pit to have a word with the three guys, Sigur Rós. And... they're so young!

I know! [Laughs.] They were like high-school kids when we first met. I liked them very much.

And they are naughty. They disobey you! They said they like to provoke the dancers with the music to make them smile!

Yes. [Laughs.]

And what do you do about that? Do you reprimand them, give them a correction?

No. I don't mind. The dancers don't change things. Sometimes timings go slightly different but at the end of the overall section it's amazing how accurate they all are.

Do you usually know the artists you bring in?

No, not always.

I wondered if you'd had a feeling about wanting to attract young people and listen to what they were doing. It had such a feeling of youth about it.

Well, it's not a question of looking for young artists, though if it happens it's fine. It's a question of looking for people who are working in visual ways that are unknown, or not very familiar - not necessarily to find someone you know, people you enjoy having around. I think it's the same with the music - the sounds of the two bands were not only interesting but new.

Had you known their music?

Had you known their music?

No. We had a meeting in London at The Place several years ago - and they sent their managers, both sides, and I think one of the performers was there. It was the Radiohead man who had suggested, amazingly enough, that each band would make a 20-minute piece. And I said, immediately, "Yes, that's fine timewise." So it wasn't a question of what came first or second. There was a question of how to do the transition, and the Radiohead guy said as we play the last note they can play their first one. (Split Sides pictured left, photo Tony Dougherty)

I know you've been interviewed 3000 times and asked the same qustions, so I asked eight choreographers in Britain to field me a question to ask you.

[Laughs tentatively.]

And I thought we'd choose them by chance, by random. I wondered if that would appeal to you?

It depends on the questions.

It depends... you'll know all the choreographers, I'm sure. So this morning I made some discs and put a number on each one. I always like things to flow logically, so I thought it would be good for me too!

[Laughs.]

Also if I put the choreographers in my order, they might think there was a pecking order, and if they come out of a hat, that's only chance.

[Cunningham picks out number 4.]

This is Matthew Bourne: do you know his work?

I know who he is.

His question: "Is Merce Cunningham interested in what happens to his work after he's gone? Is he setting up a system to preserve it, through a school or other choreographers or dancers to recreate it?"

We're doing what we can, and on the whole, I would say, given what we are, a great deal. We have in the past year brought back four pieces from the past, one 50 years old, the Suite for Five, which had no photographs, tapes, nothing, not my notes, but just memory - people would remember bits and pieces. Robert Swinston pursued it, called up dancers around the country and asked them if they remembered it, and I think it's now quite close to what it was. There are three other pieces we brought back. We are consistently rehearsing pieces from the past, partly because they're in the performing repertoire or just to keep them. And we tape them, of course.

How important to you is it that they are preserved for 30 or 50 years hence?

I don't know if that's important to me. If it happened I'd be very pleased, of course, but I think life changes, and there are bound to be things happening in a society like we have now that are shifting. But I think gradually through technology there will be a better way to preserve dance - not right away, it's too costly. One of the things is DanceForms, in its limited way you can put things on it and see exactly how they are done.

This is the software you use.

Yes. It's elementary because movement is so complex, but what it does show I think very often is that you can go back and see, oh that's how it was done. It's difficult to do with tape because that's taken from only one point of view. I admit [this DanceForms] is tedious, but it is a way.

I saw a movie, Minority Report, in which you could actually walk among holograms.

Oh yes, that's it, that's another way. It is of course technically complicated and vastly expensive, but I think those are ways through eventually to ways in which you can preserve dance.

I imagine walking through a hologram of Ocean - it would be the ultimate trip!

[Laughs.] Ocean was a big work. (Ocean pictured top by Tony Dougherty/MCDC)

Next question... (I hold the bag for him).

You made this very complicated. I use dice.

I didn't have a dice with eight sides.

I do! [Chuckles.] I have eight-sided dice with each side a different colour.

Number 1: this is Siobhan Davies.

Oh yes.

“Hello Merce, I'm looking forward to seeing you and your beautiful company. I enjoy it when a true emotion seems to bubble into my work. I love looking out for the subtle sensations that dance reveals so well. Your work has given me so many of those superb clear, hard-to-decipher stabs of feeling. Have you too been looking out for them, even through the use of chance, and if you have, has this changed over time. If and when your dancers have natural emotional expression do you enjoy taking advantage of this?”

She sees something which to her is something special and particular to her... If it happened among the dancers I wouldn't take it away, I would allow it, because I think each person is different - including each dancer - and how each dancer does something is part of how they are as a person. I don't try to fix it but if it happenes I wouldn't take it away.

She seems to be saying she lives for these moments.

I think when you do something like movement, which is so present in our lives, without any surrounding to it, anybody looking at it has to experience it - and can experience it - in his or her particular way.

But do you ever feel emotional about a movement you've created?

Oh yes. And I think particularly it becomes visible to me over the years when I am doing a dance that I may remember in a certain way, and I may even look for something I remember, some experience of that original dancer doing it. But these are not the same dancers, so the movement comes away in its own way again.

I wondered if ever you find a movement on the computer that's so great you punch the air and go “Yess!”

I wondered if ever you find a movement on the computer that's so great you punch the air and go “Yess!”

Oh, yes, I think probably I have. Oh boy! It's very difficult, but when it happens...! I think it's true. We've just been working on a film with Charles Atlas, material for it - it's very difficult to get dance on film, I think, but I think it's interesting.

It's like seeing dancers painted on a round pot, it's sort of flat, but suggesting dimensions.

Well, I think maybe it's just my eye, but with DVD there's a different kind of thing happening. Mostly in the conventional or familiar way you have a person in the back, who is one size, and when they move, you somehow don't see it, but with DVD it has a little bit more depth to it - to my eye. Somehow the idea of the moving becomes more part of it.

It's clearer.

Yes.

It may be why people have been saying DVD registers dance better.

Well, to my eye - maybe I'm making it up - but it seems to me you register the change in size as they are moving. Instead of just at the back or at the front. So we try to explore this.

A follow-up to Sue Davies’s question: I wondered if you have favourite pieces. I noticed you're bringing to London Ground Level Overlay, How to Pass and BIPED. I wondered, we've seen those, are you fond of those?

Well, they are pieces the presenters ask for, or we offer them. We are trying to keep... we can't keep all kinds of pieces, we don't want to, but we're trying to keep a variety of pieces together in practical terms, size of stage, and have enough so that we are able possibly to play in more places.

That links back a bit to Bourne's question: have you put onto DVD all your dances?

On tape? I think we have all the ones we've brought back. We tape the whole thing from one end of the studio looking into the middle, because then you get something of the back.

Often for me it's a question of just looking at what you are doing, and coming at it from around the corner

Next question.... number 7. Akram Khan, a young Londoner of Kathak background, now a very interesting new contemporary choreographer because of his background. He said: “It's about what I'm doing... I question myself. Do you consider the stage to be a temple or a laboratory? I question this in my own work. Every time I present classical work, it's spiritual, the stage becomes a temple. When I present my contemporary work it's almost more of a place where it's a laboratory, where I experiment. My quest is to find spirituality in the laboratory context.”

Oh, I understand if he's doing classical tradition Indian work, of course it would be a temple, because its base is spiritual. From my own case, if you start from possibilities, even unknown ones, due to using chance and so on as I did, it does become a laboratory. When I see one of our works in the theatre, instead of just in the studio, there's a difference. The theatre frames it in a way - not necessarily like a temple - but makes it formal.

Does that make you feel the work's spirit more when it's on stage?

Yes. Here, for example, we work on a dance for a month or whatever it is, and then we present it here as a kind of workshop situation, and you have strangers looking at it, so you see it through their eyes and I think that's very necessary.

Do you find that the work is spiritual - is that where your spirit moves, when you make dance?

I would say I am that way, yes, although I wouldn't try to impress it on the dancers. Mostly it's a question of making what it is clear to them, so that each of the dancers can find his or her way to it.

So it is, in a sense - your work is about the facts, but for you it has to be about the spirit or you wouldn't do it.

So it is, in a sense - your work is about the facts, but for you it has to be about the spirit or you wouldn't do it.

Yes, or why would one bother continuing such a difficult art? I came home once with a sad look on my face, something had happened to one of the dancers, and John Cage asked me what's the trouble? And I told him, and he said, "Oh it's a terrible art!" It is! It's frightening when you think of the kind of things that can happen, and do. But it's a world that still fascinates me. (Cunningham and Cage, left - click on the picture to listen to Cage's 16 Dances)

All right: have there been times when making a work when your spirit has deserted you?

Oh yes.

What have you done about it?

I've continued. I look at what I'm working at, try to think of different ways to do it. Often for me it's a question of just looking at what you are doing, and coming at it from around the corner.

Have you made pieces sometimes deliberately just as laboratory experiments?

Oh, I think so, using chance puts you deliberately into that, because you are immediately brought up with suggestions that are totally out of your way of thinking.

So some works your spirit was more satisfied, and others when you felt the scientist in you was more at work?

Well, I think if it, shall we say, doesn't work, then I haven't looked at it right... I think. Because I'm sure there are ways. I always think there is something new - not that I'm going to find it necessarily - but there is always something you don't know about, in this case how to do it, or how to find a way to do it. And for me it was, I think, primarily through the fact that I associated with contemporary artists, contemporary composers and people in the theatre and visual artists, whose thinking is of the time I live in. And that I love. Very difficult. Sometimes one doesn't find a way, but the problem that I'm dealing with can be so fascinating to me that I struggle on.

This links with another question, but the dice may not bring that up next. Pick again. Number 8: Jonathan Burrows. A question he's always wanted to ask you. "Dear Mr Cunningham, were you ever interested, like John Cage, in indeterminacy, meaning giving choices to your performers as to how a piece is made and performed? It seems to me that this is one idea that you didn't seem to embrace together, and I've always wondered why and what your thoughts about it are?”

Yes, I did work on it. Earlier pieces such as Scramble, certain things allowed the dancers to make choices. But first of all, I like to make movement! Selfish, I know. But also if you give a soloist something that way, indeterminacy, that is quite possible, but when you have two or more people in indeterminacy, there are possible collisions - it can become quite serious. It was many years ago now, actually, but we were in a workshop and had indeterminate elements, and one dancer ran into another, and nobody was seriously hurt, but they began to see that there was something about this that was risky. I think within certain limits it can work, and we still have it in our Events portions where the dancers can make choices. Though the choices are limited.

It's interesting you say you're selfish.

Well, it's what I do!

Because it's a very controlling method, this chance method - because you have to have very controlled elements and apply chance to them.

Yes. The kind of material going into it is, and I make enormous numbers of notes! [Laughs.] But by breaking down details about where an arm goes in relation to the leg, for instance, the complexity of working this way is fiendish, but fascinating.

Watch an excerpt of a film of Points in Space, made in 1986 by the MCDC:

Would indeterminacy need more reliance on improvisation? And I've seen you complain that improvisation tends to be simplistic, one idea at a time, whereas you could build complexity?

Well, somehow I like complexity so I'm willing to fight for it. I'm basing my experience on several years back when I gave workshops with very limited students whose physical abilities were not elaborate but which did involve improvisation, and I began to see they always did the same thing, and would repeat it in the same space or same time. I made suggestions about other ways but they would go back because they were comfortable. Now, chance does not make you comfortable! It does not make me comfortable! Heh heh! But at the same time I find it an eye-opener.

It's also for you a familiar way to work - by using chance on the ingredients you assemble, you remove the chance of something getting out of control.

In the sense that you take these elements that come up through the chance procedures and try to deal with them.

But it can't be anarchy! Because you are controlling all the elements.

Well, anarchy would be interesting, but difficult! Because of the physical aspects of dance, of movement.

People sometimes call your work classical...?

People sometimes call your work classical...?

I don't care. If by classical they mean stripped of decoration, that's all right. I think movement by itself, when it doesn't have a particular inflection or surrounding or whatever, allows each person to see it in his or her own way, and it can have a force that somehow gets lost when it's slanted. Now, I'm making it so that basically it somehow comes from me, I agree to that, but if I see working with the dancers through the chance procedure that this could happen this way, which isn't quite what the chance thing said, but it's working for the dancer, then I'm all for it. (Pictured, Summerspace, 1958)

Jonathan and probably most of the choreographers are from a generation when the choreographer/dance relation is much more of a collaboration - and I think Ashton and Balanchine often said to the dancer, “Show me something.” There is a different authority balance: it's more equal, matey between them, rather than the parent telling the child. You are unusual in that your dancers are there to be your instruments.

Yes, but they are also people. And individuals

And you love them.

Um... [seems disconcerted]. Well, yes [inflects upwards]. Oh yes. And I think without the way we work together we wouldn't have what we have - whatever that may be. But take for example our daily attempt to have a class, wherever we are touring, no class is ever the same. Partly it's because I could never remember what I'd given them before, but I think it's also that over the years, if you open your mind, and don't just remember certain kinds of ways of moving, that gives you a chance to find new things, or even the same kind of thing but in a different way.

In life too?

Yes.

Do you use chance in life?

Well... like crossing the street? [Laughs.] On occasion. Not any more, I must admit. But yes, I did. I would toss a coin. When I was very poor I remember I had something like a dollar and I had just finished an errand, and it was time to go home to my place, which had a leaky roof. And it had just started to rain, and I was starving. So I had the choice - take the bus and have nothing to eat, or walk home and buy something to eat. I tossed the coin and took the bus.

And starved! And been thin ever since!

Oh... [laughs].

Watch Merce Cunningham perform Septet with his company in 1964

Next question, number 6. Henri Oguike, who I think is a wonderfully musical choreographer, one of Richard Alston's students. He asks this simple question: if you weren't a choreographer, what other career would you have been drawn?

I don't know if I can answer that exactly, but at the moment I like drawing, and I've been drawing for years now - I just enjoy it. So it might have been something visual.

Have you ever got bored or fed up with your work? Had a mid-life crisis?

It may be why the drawing came up. It was 20 or 30 years ago... We were waiting for a bus, we'd got up early, and the bus was delayed. And I was sitting in the hotel and there was a tree outside the window, and I thought, well, can I draw this? I got a pencil and scribbled. And the doorbell rang and they said, "The bus is here," and I said, "It's early." They said, "No, it's 10 o'clock" - two hours had gone by. I realised, I'd found something to do, and I've been doing it ever since.

And you admire visual artists, don't you? You have quite a collection of art.

Yes, I do. But mine are just for me, I just like drawing. If people look at them I don't object, but it's just what I like doing.

There was certainly some kind of logic in our government going to war with Iraq, but what kind of logic, and what kind of use has it been?

Disc number 3: Michael Clark. “You once said, ‘There's no thinking involved in my choreography.’ That seems such a radical thing to say. How could it be possible to make choreography without any thought?”

I think my saying that is a mistake, because there is thinking, but it's not about what it refers to. It's about looking at a movement and not trying to add something, to let it be what it is, and find out how to make that. And that is thinking.

So it was more of a defensive remark, to stop people looking for definitions?

Yes, that was what it's about.

Because you are removing logic, human mental logic from it...

Well, logic has put us in all these wars.

You think logic is a bad thing?

There was certainly some kind of logic in our present government going to war with Iraq, but what kind of logic, and what kind of use has it been?

Coming from my very logical and classical music background, when I first saw your dances, I was struck by how human they were, but also they seemed to reconnect human beings with animality as if to remove human verbal logic. I wondered what human experience had taught you about logic?

I don't think I'm wary. Well, in a way I am, because this logic has led us into these things. But there are other ways to think about how life is. And if your mind can open up... Because without men's minds opening up we wouldn't have the kind of progress that we have. Logic has led us in certain ways, and then somebody comes up, like Einstein [laughs], that shows you how logic is nonsense, that there is something else. It was that remark of Einstein's that changed my view about space - I'm talking about dance space. He said, there are no fixed points in space, and I thought, my god that's marvellous for the stage! Rather than thinking there is a fixed point on the stage, the most important place, allow for any point to be used, so that you can not only face it but use it for directions.

Was that a turning point for you to abandon logic in dancemaking?

It was one of them, but a very vivid one. I think it was in the Fifties - that long ago.

Was there a point that you remember you thinking, "I won't use body logic - I will defy it"?

I wouldn't say I put it that way, but I remember before Einstein's statement, when I began to make solos, to work out to think in the space that I was turning into what you could call conventionally, front, side, centre and so on - none of it appealed to me though I had no other way to think of it. That statement crystallised it for me. But that means the whole area in which you perform, which allows us to perform in the studio, or do these different events in places like the Piazza San Marco [laughs], simply because you take the space for what it is, not something in which you place something already conceived.

It's so odd that nobody else has done this. Is it just because it's such damn hard work? [Laughs]

It's so odd that nobody else has done this. Is it just because it's such damn hard work? [Laughs]

Oh yes. [Laughs] But take the Tate in London last year, a totally different kind of space (pictured right). How do you put a theatre in there? How ridiculous. Rather than taking it for what it was - and we also had the gift of Olaf Eliasson's sun. Oh, imagine! The decor was extraordinary! I walked into the space the previous year to see the possibilities and thought this would be a marvellous place.

You didn't know you'd get Eliasson's sun then.

No, I found out later and I thought, well, that's superb. I hadn't seen it until we went in to perform.

Real-life chance!

Yes!

Next question... it’s number 5. Richard Alston. “It's exactly 60 years since your first New York concerts with John. You're still making complex dances with complete rigour and focus. How on earth do you do it?”

Is it 60? I don't know. The one thing I can say is that, difficult though it is now, in my physical condition, I remain fascinated by movement. I don't have any other reason, except that when I'm going about I keep seeing something. The other day it was, oh, on the television, watching the hurricane, and those trees [he bends his hands]. It was the movement of them. I've so often seen people in the street and just watched them walk, how does this one move different from that one? That's a basic. And I keep coming across - I don't know how else to describe it - but rhythmic things that I haven't experienced, like a simple step that you might think is very ordinary, but I see a way rhythmically to change it - and that means I have to get the dancers to try it out. And for a moment I've looked at something familiar in a different way.

Now that you can't dance any more, do you feel differently about movement? Does it make you process them differently, now that you can't demonstrate them?

In my head, you mean.

Like Beethoven going deaf, heard music differently.

Yes. I have to see the movement in my head and then, of course, tell them how to do it! [Self-deprecating laugh.]

But did you always make movement as complex as you are making now for them, as you've been able to do it less and less yourself? Did you move like that yourself?

Oh yes, I think they weren't the same kinds of complexities, but I remember several solos I made for myself when I started with chance processes, and there were these separate elements for hands and arms and legs, and it was very difficult to do, very difficult to remember. Because it wasn't in one's own physical memory. That's one of the things... Since working with the dancers, say 10 years ago, some of the things I do now would have been very difficult for them not only to do but to remember, because it didn't fit any patterns. But they got it, though it took a while. But now they pick things up almost from one looking.

Extraordinary - how?

I don't know how it is. But all I can explain is how it's like television now, there are three or four things going on at the same time - I see what they're saying, or hear it, and I'm also reading the bottom. We have that in our daily lives so we accept it and use it. Well, with the dancers now, and in classwork I've noticed too, I make things which are complex, and it doesn't mean they don't have to work at them, but they see them quicker.

Their habits are different.

Yes. And one thing for me is how not to think that the habit is the only thing, the only way to do something. Look at it, maybe there's another way. I've often been to dance programmes where they might do an interesting phrase, but they repeat it - we don't do that, we allow for change.

All I can say is that I'm interested in looking for things that I don't know about, and they're harder to find

How about your consistency? Because this consistency is unusual, no one has made top-quality dance as long as you have.

I don't know the reasons. All I can say is that I'm interested in looking for things that I don't know about, and they're harder to find. And I have to really think in my head, and when I see them, dancers like working on them. Film work makes it very hard to put something on and make it work unless you think in film terms, and that for me is another change. When I began with Charles Atlas way back, 20 years ago, more, whatever, he is a film person and he was our manager or something, and I said, "Well, I've never had anything to do with this," and he said, "Here's a camera, look through it." I noticed two things, that it didn't look like dancers thought it would look like, and the space was completely different.

When technological changes come along, you get very excited about them, and last time we met you told me you are plugged into your Apple Mac for hours.

Yes. (Image right from Biped, 1999, MCDC)

Yes. (Image right from Biped, 1999, MCDC)

But if you could turn your dances into virtual dances, through technology, would you do so?

I would love to try. I would love to be involved more in other kinds of things like motion-capture, but it does involve enormous expense and studios, so we don't have that. But I would be... [laughs] interested in trying.

Your work lends itself to virtual reproduction - it would be extraordinary, wouldn't it? To walk in among one of your dances, especially if it were 30 years old.

Oh yes. [Enthusiastic.]

One question comes out of Richard's point - have you ever had creative block?

Oh, I'm sure I have.

Or any times when you ground to a halt, like Michael Clark?

Oh, no, not that. I get depressed when I can't seem to think about something I'm working on. I'm usually halfway through and I think it's awful, so I just keep going back over it thinking how to do it in another way. I don't give up. [Chuckles]

Does technology help you out?

Oh yes, I think it does. Whatever it is or isn't, using Lifeforms or DanceForms as it is now really opened my eye to another way of looking.

And it continues? Doesn't become routine or mechanical?

No, not yet, I don't think so yet. I know it can. With the film piece, for instance, I put a great deal into the computer, not exactly as it will appear on the film, but it starts you, you see something - and I begin to wonder, oh, maybe we can do it this way or this way.

Do you try to make sense of the world through your dance? Or do you try to get away from it!

No, I think it's given me a way, personally, to be. To be able to look at this craziness that we live in and find a way to continue. I mean, look at this society. It's frightening. Well, if that's what you want to deal with, fine. But I don't. I just want to find a way to work, and let people see it if they want to.

You're trying to control crazy events?

Oh no, no.

I mean, you're surrounded by crazy events, and what you are doing is actually making your ingredients, and giving them disorder yet not losing control of them.

To me, it's not disorder, to me it's a way of ordering it. Since Ocean - that was six months, and that was incredibly difficult but a marvellous experience to work at. First of all, as you know, it's on the round, so I came here - used to come on Sundays, to be by myself - and I drew the circle, and I had by chance operations made some phrases to try out, and I'd learned them so I'd be able to do them! So I stepped in with my first phrase, and suddenly thought, which way do I face? On stage, as you know, there is always a focus, you can face another way, but this is the focus. But here, any way, was right. So I had to use chance means to determine the way every phrase should face.

It took six months - I'm not surprised.

But it was fascinating.

Pictured below, at the Pittsburgh Museum, Andy Warhol's Silver Clouds (1966), used by Cunningham in his dance Rainforest

One more question here... Number 2: Russell Maliphant asks: “I'd be curious to know how much his work with collaborators has informed his growth in creating over the years, and does his continuing work with other collaborators shift his thoughts about creation or consolidate earlier findings (or both).”

I think collaboration certainly with the visual artists and musicians has been an extraordinary experience of aspects of our artistic time now, and that's what I really wanted. First of all with Cage, of course, but to work with artists who seemed to me not to be repeating things from the past but always looking at the world they lived in in a different, new way.

So that's your guiding principle in choosing them? Not to have old-fashioned ones?

No. It's easier, for example, to take an old piece of music and put dance to it, because its structure is known and familiar. I was interested in the fact that visual artists, for example, were using new materials that didn't exist previously, or finding new ways of making art - for instance, the whole art of collage is a 20th-century artefact.

But if you don't let what they are doing affect what you are doing, it's immaterial!

In a way, yes [laughs]. And Cage's premise was that any sound was available, so if you allowed for that you had to allow for an even greater magnitude. But movement has limits - there are certain physical facts about the human body, only two human legs, not three, and there are certain facts about it. But at the same time, the variety of those facts is endless.

Would you use Brit artists like Tracey Emin's bed or Damien Hirst's formaldehyde cases?

Yes, but I have to be a practical performer and say, we want to show what we do, and we need things that are practical for us. We have had two or three times artists who made things that could only be used once and they were interesting but we could use them - a marvellous set by Frank Stella that we had for a work called Scramble which was a series of bands which were on wheels, could be moved, 16 feet - they were modules, they were very beautiful and I loved them, but we couldn't get them onto stages. And there was a wonderful, I thought anyway, set by Robert Morris for a work called Canfield, which had indeterminacy in its procedures, it was beautiful what he made, but same problem - there were many theatres in which it couldn't function.

Do your collaborators always understand your purposes, or do they argue a bit?

Sometimes... but somebody like Robert Rauschenberg, he's a theatre man and he understood about dancing, and realised immediately the practical side. (Pictured left, John Cage, Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg.)

Sometimes... but somebody like Robert Rauschenberg, he's a theatre man and he understood about dancing, and realised immediately the practical side. (Pictured left, John Cage, Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg.)

But what about them not getting a steer from you? Do they always ask you “what sort of piece”?

Yes, they will ask... I always say I will give them any information they want. The principle is simple that we are three separate identities, making something that can function in the situations that we get into. Sometimes they would see something and realise it was just not practical to care for and get from one place to another, but many times they were very open, and say, “What is the dance?” And I say, "You are welcome to come and look at it but I'm not going to tell you what to do."

Do they find that hard?

Some of them. But some of them took to it.

Did anyone tell you they wanted to do something very fizzy or very tragic, and you ought to know - and do you say, I just don't want to know?

I don't think anything like that. But they do ask practical questions. It's a gamble, I know, because one doesn't see what's done. I remember one time at the City Centre, I think it was Ground Level Overlay, the set by Leonardo Drew. Music by Stuart Dempster using the conch shell. I hadn't seen the set. I came into City Centre, and we were going to rehearse and there was the set, and I said, "Oh, it's marvellous" - all these extraordinary objects hanging off it. I said, "Let's get going." And Stuart said to me from the pit, "Merce, are you going to run the dance? If so, do you mind if I play the music?" I said, no, it would be the first time I'd heard it. You risk, I know, but they add things I wouldn't have thought of, both visually and the sound. It is a risk, I don't question that.

Have you ever actively disliked something?

There was an event we did here in New York... I don't remember his name, probably purposely. John said he thought we should ask him, and it was difficult soundwise, and he was running around shaking things and it was somewhat impractical.

He was getting in the way of the dance?

Somewhat. I wouldn't mind that, we have done things with musicians on stage, but as Cage says, it's a question of choreography not to bump - in other words, not to have accidents.

Choreography not to bump! A good rule.

[Laughs.]

If you didn't like what a collaborator had done, would you ever re-use a piece of choreography and ask a different collaborator to make something different for it?

There was a point, way back, where what someone had made didn't work, and he knew it, the composer. And John did something different for us.

For instance, Sigur Ros made that lovely kind of xylophone of ballet shoes for Split Sides...

[Laughs] I want that! The ballet shoes that they put on the rack thing and hit? Wonderful.

I wondered if you'd take it home and put it in your collection.

We asked to have it, but I think they have it!

They said they used ballet shoes because the dancers would hate them!

Yeah! [Laughs.] I thought it was marvellous, and the sounds they made with them.

I have a question of my own - have you ever had a brain scan?

Oh, I, Oh, I... [disconcerted]. I hope not.

Because I think it would be fascinating.

Oh, I don’t think I would want to go through that.

I would think a neurologist would be fascinated by your brain. I've been speculating that by removing emotional stress, removing emotion which most people use as a trigger or feed from your work...

... Yes...

In some ways, that has helped you to create longer.

I think so. I agree. Because you get yourself out of the way. I try. I remember a dancer saying, “Oh, I want to do that again and again.” I like movement, I love it, but I want to have as many different experiences with it as I can manage.

Most of these questions from these choreographers are all trying to home in somehow on understanding why you don't use emotion, because they all do use it.

Well, I don't know. But I didn't ever think of it. Maybe when I began, I did.

Did you find the choreographers' questions interesting?

Yes. They all centred about themselves. Well, everybody does. It's just not the way I work.

Cunningham Through the Years

- 1919 Born 16 April in Centralia, Washington, to a small-town lawyer, second of three sons. Studied dancing locally.

- 1938 Met composer John Cage (born 1912) at the progressive Cornish School of Arts, Seattle. Influenced by Zen Buddhism, Dada and American Indian spirit dancing.

- 1939 To New York to join Martha Graham Dance Company, became her leading man.

- 1941 Visiting Graham, the blind Helen Keller learned what dance was by touching Cunningham as he jumped. He never forgot her remark: "So light, like the mind."

- 1944 In Martha Graham's Appalachian Spring, Cunningham played the rabid Preacher, choreographing his own solo. First dance concert with Cage.

- 1945 Left Graham to go independent. 1952 Black Mountain College, North Carolina, Cage and Cunningham's first "event", a collage of chance "happenings".

- 1953 Cunningham company debut in New York. The only review, in a German paper, was headlined: "Dance led astray".

- 1955 First US tour, in a camper van with Cage, artist Robert Rauschenberg, five dancers and two musicians.

- 1964 First world tour and London debut. Critic Alexander Bland wrote: "Diaghilev would have loved Cunningham."

- 1979 First film-dance, Locale, launched a decade of exploring dance on camera.

- 1990 Started choreographing with computer software.

- 1992 Cage died. Cunningham returned to work the next day on Enter.

- 1994 Ocean, an epic circular work.

- 1999 BIPED, futuristic visions with motion-capture video, performed in UK.

- 2003 Tate Modern Event under Olafur Eliasson's gigantic sun installation. Split Sides premiered in New York.

- 2004 Split Sides in London with Sigur Ros

- 2009 Nearly Ninety premieres on Cunningham's 90th birthday. On 26 July he dies. Read a tribute here.

Watch a filmed interview with Cunningham and John Cage in 1981

- The Merce Cunningham Dance Company performs Nearly Ninety at the Barbican Theatre, London tonight till Saturday

- The company's "Legacy tour" continues 17 Nov, Maison de la Culture, Clermont-Ferrand, France, with CRWDSPCR, Antic Meet, Sounddance; 20 Nov, Centre Pompidou Metz, France, with Nearly Ninety; 24 Nov, Maison de la Culture Grand Théâtre, Amiens, France, with Nearly Ninety; 2-4 Dec, Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts, Miami, Florida with Event - all details here

- More information about what's on in Dance Umbrella

- A celebratory DVD, A Lifetime of Dance, is available from the Merce Cunningham Dance Company website

- Find Fifty Years, a magnificent large-format book by Cunningham's archivist David Vaughan, on Amazon

- Find the DVD of Split Sides (2009) with Sigur Rós and Radiohead music on Amazon

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment