Jérôme Bel, Cédric Andrieux, Royal Opera House Linbury Studio | reviews, news & interviews

Jérôme Bel, Cédric Andrieux, Royal Opera House Linbury Studio

Jérôme Bel, Cédric Andrieux, Royal Opera House Linbury Studio

What did a Merce Cunningham dancer think about as he rehearsed? It's not much like Fame

Dance is eating itself. Or dancers are eating themselves, rather. It's on-trend to defy the idea of the mute dancer, and instead have them verbally explaining themselves, their motivation, their art. This year’s Dance Umbrella launched last night with the “self-contemplation” of Cédric Andrieux, a handsome blond Frenchman, who regales us in a charming murmur for 80 minutes with the story of his career, with danced illustrations.

I have nothing against a chap expressing himself to me, especially when he has as gentle and self-deprecating a delivery as Andrieux, but I'm largely with Ray McCooney in Little Britain here: "Let me tell you through the medium of dance." Anyway, Andrieux (now 34) recounts deadpan how as a child he was fired by seeing the title credits for Fame on TV, and how when he was to be accepted into the Paris National Conservatoire of Dance, it was the French version of Fame.

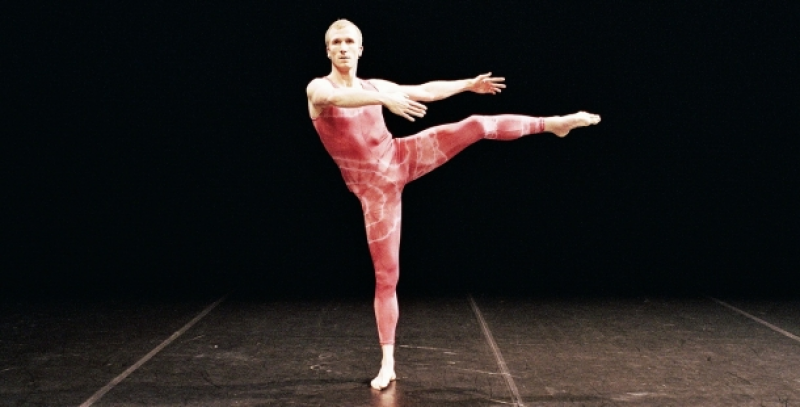

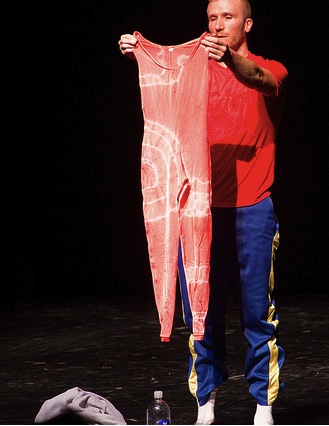

That may be as side-splitting as it gets for the general watcher. If you know who Trisha Brown, Maguy Marin, Angelin Preljocaj, Merce Cunningham and Dominique Bagouet are, you’re in for a banquet of dropped names. The Cunningham connection in particular is germane, as Andrieux spent eight years in the celebrated New York company, and his faintly satirical demonstration of a typical daily class (metronomically clicking tongues the only sound) sheds more light on the late, great choreographer’s remote personality than usually emerged in interviews. No corrections afterwards from the master, no comments - "totally depressing". (Andrieux contemplates his unitard, pictured below © PICA Portland Festival 2010/Wayne Bund.)

He also demonstrates the cruelly laborious choreographic process of the computer methods used by Cunningham - the legs doing a chain of very difficult disconnected things, the torso adding almost sadistic counter-intuition, the arms then rigidly applied in dogmatic shapes. None of it logical to the body, none of it flowing, all of it hard, emotionless graft. "I often had this feeling of humiliation," Andrieux murmurs.

He also demonstrates the cruelly laborious choreographic process of the computer methods used by Cunningham - the legs doing a chain of very difficult disconnected things, the torso adding almost sadistic counter-intuition, the arms then rigidly applied in dogmatic shapes. None of it logical to the body, none of it flowing, all of it hard, emotionless graft. "I often had this feeling of humiliation," Andrieux murmurs.

Then he performs a section of BIPED, one of Cunningham’s most haunting pieces, but in which he is just one small moving part in the construction kit. Even a short stretch has him panting too hard to speak for a while, and you wonder what possible reward he derived from his years of dully exacting class and incomprehensible dance orders. What he doesn’t talk about is how all that Meccano with its wonky angles turned magically on stage into purest, most delicate, most suggestive dance filigree, as incomprehensible as spring water, because what wasn’t in the computer was Cunningham’s incorrigible showmanship.

That is the key dimension missing here, the insight that doesn’t come. The dancer's self-contemplation is just about disarming enough to avoid being conceited, but it cuts out where it ought to become interesting: how it is that the dancer may sense that the choreography he is doing, even if he doesn’t understand it, has a mighty integrity and super-dimension of its own, offered as a privilege to the audience. What is it like to be a vessel? Can you tell the difference between carrying holy water and bog-standard not-drinking water, choreographically speaking?

I’m not sure whether one can blame Andrieux for this or the evening's conceiver/creator Jérôme Bel (another name to drop in the elite cloisters of European dance), who's made a name for himself by creating solos of self-contemplation for other dancers, including one at the Paris Opera Ballet. So perhaps it's Bel who doesn't want Andrieux to spill the secrets.

Still, when Cunningham’s company performs its last ever British performances this week at the Barbican, Andrieux will have at least provided an elementary primer, and some wicked thoughts about how bored even the most devoted dancers might be as they chop and mutate their bodies into those strangely delicious shapes.

- The Merce Cunningham Dance Company's farewell London visit, with three programmes, is at the Barbican Centre, London 5-8 October. BIPED will be performed on the Saturday, 8 October programme

Watch the opening section of Jérôme Bel's "self-contemplation" film of Paris Opera Ballet dancer Véronique Doisneau

Buy

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment