Alighiero Boetti: Game Plan, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Alighiero Boetti: Game Plan, Tate Modern

Alighiero Boetti: Game Plan, Tate Modern

Playful, sensual and extraordinarily beautiful, the work of this conceptualist is an absolute delight

Two superb exhibitions at Tate Modern bring into public view the work of Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama and Italian conceptualist Alighiero Boetti; their work is not in any way connected except that, with their singular voices, each deserves much broader recognition.

Conceptualism often gets a bad press because people associate it with those artists who, more interested in ideas than products, rely on others to translate their concepts into objects. The approach is seen by many as a dereliction of the relationship between an artist and their materials, which some consider crucial if an object is to be considered an artwork rather than an industrial artifact.

There’s no doubt that Boetti was an ideas man; one of his titles refers to the six senses – thought being added to taste, hearing, smell etc. Made in 1993 shortly before his death, his bronze Self-portrait (pictured below) shows him standing under a hose pipe; hidden inside the skull, a heating element turns the water into steam, as though his fevered imagination were causing his brain to over-heat! And Boetti routinely collaborated with others, but as this exhibition reveals, the resulting artworks are often ravishingly beautiful and extremely sensual. He may have been a conceptualist, but he was also a sensualist.

Born in Turin in 1940, Boetti started out as an Arte Povera artist using mundane materials bought from the local hardware store or cake shop and arranged in simple configurations. A stack of doilies produces a crenellated column; extended at the core, a roll of corrugated cardboard resembles a giant pencil, while a perspex cube is neatly filled with a disparate array of packaging material, so that texture and colour take precedence over usage.

Born in Turin in 1940, Boetti started out as an Arte Povera artist using mundane materials bought from the local hardware store or cake shop and arranged in simple configurations. A stack of doilies produces a crenellated column; extended at the core, a roll of corrugated cardboard resembles a giant pencil, while a perspex cube is neatly filled with a disparate array of packaging material, so that texture and colour take precedence over usage.

The sculptures are so simple they seem to have made themselves; the lighter the intervention, in fact, the more compellingly self-evident the outcome. The artist’s role is to point out the hitherto overlooked. Boetti referred to artists as "i vedenti” (the sighted) and called this process of focusing attention on mundane things “bringing the world into the world”.

But he tired of being at the forefront of a movement that had been named by curator and critic Germano Celant mainly for publicity purposes and, in the late 1960s, he took off for foreign parts. Working on the hoof, as it were, he began making use of the postal system. He wasn’t the only one: in the early 1970s, Douglas Huebler and Gilbert & George were among those disseminating ideas by post. Cards sent by Japanese artist On Kawara stating “I am still alive” used to drop through my letterbox along with invitations from Gilbert & George, instructions for sculptures by Lawrence Weiner and cryptic phrases by Joseph Kosuth.

Subtle shifts in scale, density and colour produce wave-like patterns resembling water

Boetti didn’t use the postal service simply as a means of communication, though, but to produce the work itself. Sometimes he arranged stamps according to every possible colour permutation, sometimes he turned them upside down to encode political messages. Letters were sent to fictitious addresses and, on their return, were photocopied and posted in fresh envelopes to further fake addresses; the process was repeated until a dossier of failed communications was built up – testament to a system that was trying to deliver, both literally and metaphorically.

His fascination with systems, rules and the many forms of classification, numbering and ordering that govern our thinking and behaviour was matched by rebellious delight in their disruption. He subverted the perfect geometry of the grid, for instance, with hand-drawn lines whose imperfections produce wobbly, undulating patterns.

Add to this a love of banal materials and you get some of the most unexpectedly sublime images of the 1970s. Using blue biros, his assistants filled sheets of paper with row upon row of tiny strokes. Despite their best efforts to achieve uniform surfaces, subtle shifts in scale, density and colour produce wave-like patterns resembling water. Punctuating the drawings are white commas which, from a distance, look like stars in the night sky; by referring to letters of the alphabet written down one edge, they spell out phrases such as The Six Senses.

He employed Afghan women to transform his ideas into embroideries which subtly subvert Western thought

Near his studio in Rome, a church bell rang out the hours and quarters. In a drawing shaped like a tree, Boetti charted the inexorable chimes and commissioned embroiderers to translate the image into tiny cream stitches. Not only is the embroidery a thing of enormous beauty, but it challenges preconceptions about the relationship between art and craft and, more importantly, about our attitude towards time. By embodying a notion of time as slow, calm and meditative, the embroidery exposes the way our concept of time as a relentless march often turns our lives into a battle against the clock.

The women who embroidered The Hour Tree (1979) were Afghans. During his wanderings Boetti visited Afghanistan and fell in love with the country; he set up a hotel in Kabul where he stayed during many subsequent visits and employed Afghan women to transform many of his ideas into embroideries which subtly subvert the determinacy of Western thought. When during the Russian occupation it became impossible to visit the country, he travelled to Peshawar and employed Afghan women from the refugee camps, thus offering them much needed economic support.

How do you measure the length of a river – in spate, in drought; at high or low tide; along one bank or down the middle? Classifying rivers was never going to be an exact science, which is why this fruitless task appealed to Boetti. After years of research, he and his wife produced a list of the thousand longest rivers, which they published as a book and commissioned as an embroidery. The names – from Nile and Amazon to Moksa, Koto and Beaver – are listed in a digital font whose anonymity contrasts with the hand-stitching of the needlewomen; a fast, impersonal, electronic mode of communication associated with efficient data collection is rendered in a medium that being slow, personal and traditional opens a window onto alternative modes of thought and communication.

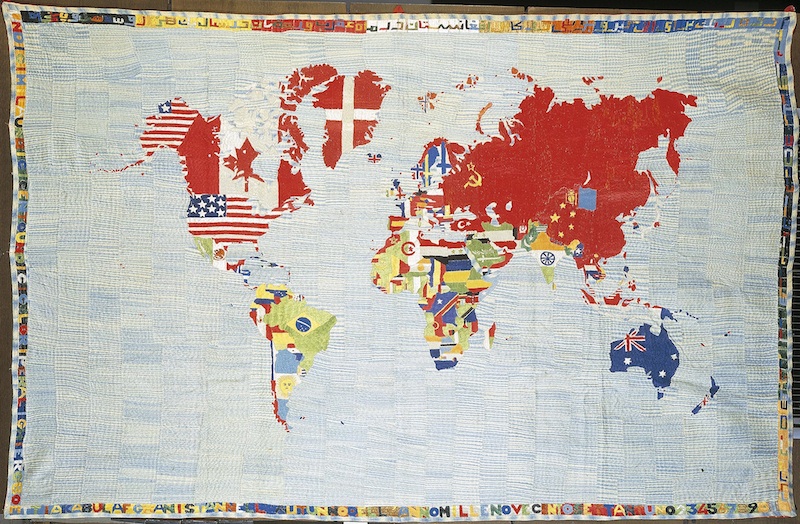

And how do you represent the world in a map? Various different projections prioritise one view over another by laying emphasis on the northern or southern hemispheres. For his maps – the ultimate example of “bringing the world into the world” – Boetti used several different projections and filled each country with its national flag. From 1971 until his death in 1994, he produced over 200 examples (see main picture) and, during that time, changes in the design reflect world events such as the break up of the Soviet Union and the civil war in Namibia, which was shown blank while the country had no national flag.

And how do you represent the world in a map? Various different projections prioritise one view over another by laying emphasis on the northern or southern hemispheres. For his maps – the ultimate example of “bringing the world into the world” – Boetti used several different projections and filled each country with its national flag. From 1971 until his death in 1994, he produced over 200 examples (see main picture) and, during that time, changes in the design reflect world events such as the break up of the Soviet Union and the civil war in Namibia, which was shown blank while the country had no national flag.

On one occasion, Boetti forgot to specify the colour of the sea and when it came back green, he was so delighted that he left future choices to the embroiderers who produced pink, silver, yellow and black versions. In the borders, the Afghans were invited to embroider comments reflecting on their lives and aspirations so that, once again, our Western perspective is subverted by the inclusion of other viewpoints.  Playful, irreverent and, above all, supremely beautiful, Alighiero Boetti’s work gently nudges us into reconsidering some of our basic preconceptions – in particular, the supremacy of western modes of thought over other, older systems. Don’t miss this wonderfully life-affirming exhibition.

Playful, irreverent and, above all, supremely beautiful, Alighiero Boetti’s work gently nudges us into reconsidering some of our basic preconceptions – in particular, the supremacy of western modes of thought over other, older systems. Don’t miss this wonderfully life-affirming exhibition.

- Alighiero Boetti: Game Plan at Tate Modern until 27 May

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment