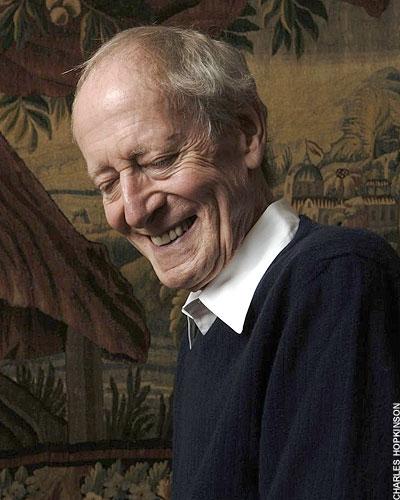

“When you write for film, the dialogue is like the voice, if you like, and I always consider that as part of the music,” said John Barry, who died on 30 January. “Certain orchestral textures have to match the texture of the scene. You deal with the lightness and darkness of the scene when you write music for cinema. The film is a part of the score, and you can't get away from that.

A comprehensive list of soundtrack composers would run into several volumes, but among the elite handful which includes names like John Williams, Ennio Morricone or Maurice Jarre, John Barry stands as tall as any. His sound became synonymous with James Bond, but although he worked on a dozen Bond films, that was a small part of a prolific career. While many soundtrack specialists are best known for a handful of key works, Barry is exceptional for the variety of moods and styles he was able to encompass in a career stretching back to the 1950s.

He admitted he'd been fortunate to be in the right place at the right time. He got off to a flying start by being the son of Xavier Prendergast, who ran a chain of cinemas in York and introduced his son to the wonders of the silver screen from earliest childhood. He enjoyed early professional success with his band, the John Barry Seven, but it was when he was asked to score the 1960 Adam Faith movie Beat Girl that he set his sights on becoming a full-time film composer. Happily for him, London was on the brink of a movie boom, in which Barry would find himself working on as many as eight movies per year.

“I always thought to write film music I'd have to go to Hollywood, but in the Sixties all those guys came to England,” Barry recalled. “With the James Bond movies, [producer] Cubby Broccoli was American, Harry Saltzman was Canadian, but it was all United Artists money. Suddenly America came to London in the Sixties, all these directors and producers came over here, and I was there ready.”

“I always thought to write film music I'd have to go to Hollywood, but in the Sixties all those guys came to England,” Barry recalled. “With the James Bond movies, [producer] Cubby Broccoli was American, Harry Saltzman was Canadian, but it was all United Artists money. Suddenly America came to London in the Sixties, all these directors and producers came over here, and I was there ready.”

It's ironic that the trademark "James Bond Theme", the one played by a twangy guitar, was composed by Monty Norman and only arranged by Barry (when the Sunday Times claimed otherwise years later, Norman won £30,000 in damages), but the Bond series gave Barry scope to show his musical paces. Aside from his towering theme tunes like Goldfinger, Thunderball and Diamonds Are Forever, Barry used raucous brass arrangements and heart-stopping minor keys to evoke sweeping vistas of drama, danger and glamour, his music sometimes proving more memorable than the movies themselves.

However, by the time he reached 1979's Moonraker, Barry was ready to ring some changes. This time, he created his soundtrack with lush, unhurried string arrangements, a technique he would continue to develop on future projects such as Out of Africa or Kevin Costner's majestic western, Dances With Wolves. His soundtrack for Born Free in 1966, with its theme tune which became an easy-listening standard, had dropped an early hint about his affinity for films about open spaces and epic landscapes.

But the urban side of Barry has been a recurrent strand in his work too. For the New York lowlife of Midnight Cowboy (1969), Barry constructed the soundtrack from a selection of newly commissioned pop songs, designed to match the shifting moods of the story. It was a technique that Hollywood would imitate to death over the coming decades. Barry was a long-standing jazz enthusiast too, and his soundtrack for Francis Coppola's Jazz Age crime story, The Cotton Club, found him splashing about energetically in fresh arrangements of pieces by Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway to recreate the feverish atmosphere of Harlem in the 1920s. For the thriller Body Heat, Barry deployed a small jazz combo, flavouring the mix with synthesisers.

But the urban side of Barry has been a recurrent strand in his work too. For the New York lowlife of Midnight Cowboy (1969), Barry constructed the soundtrack from a selection of newly commissioned pop songs, designed to match the shifting moods of the story. It was a technique that Hollywood would imitate to death over the coming decades. Barry was a long-standing jazz enthusiast too, and his soundtrack for Francis Coppola's Jazz Age crime story, The Cotton Club, found him splashing about energetically in fresh arrangements of pieces by Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway to recreate the feverish atmosphere of Harlem in the 1920s. For the thriller Body Heat, Barry deployed a small jazz combo, flavouring the mix with synthesisers.

But one of his most original soundtracks dated back to 1965, when he composed the score for The Ipcress File. With Michael Caine playing the anti-hero, Harry Palmer, as the kind of down-at-heel flip side of James Bond, Barry concocted a masterly un-Bondlike soundtrack bristling with mystery and menace, largely through his use of the cimbalom. Technically, the instrument is a hammered dulcimer of Eastern European extraction, and Barry daringly thrust it into the foreground, where its harsh, metallic tone sounded like a giant skeleton with electric shocks running up its spine.

It's possible that Barry had been inspired by Anton Karas's soundtrack for The Third Man, with its equally distinctive zither. “Some directors will tell you they know a lot about music, then when you work with them you realise they know precious little,” Barry observed. “A good director will be honest with you. When I worked on Carol Reed's last movie, Follow Me, he said, 'The most terrifying thing about movie-making for me is the music. Everybody thinks I know all about music because of The Third Man, but it was my wife who found Anton Karas. I listened to him in this cafe in Vienna and I said, "Well, yes," and we did it, and everybody thinks it's the most brilliant thing.' But it was one of the great movie scores ever, in terms of simplicity and style and character.”

It's possible that Barry had been inspired by Anton Karas's soundtrack for The Third Man, with its equally distinctive zither. “Some directors will tell you they know a lot about music, then when you work with them you realise they know precious little,” Barry observed. “A good director will be honest with you. When I worked on Carol Reed's last movie, Follow Me, he said, 'The most terrifying thing about movie-making for me is the music. Everybody thinks I know all about music because of The Third Man, but it was my wife who found Anton Karas. I listened to him in this cafe in Vienna and I said, "Well, yes," and we did it, and everybody thinks it's the most brilliant thing.' But it was one of the great movie scores ever, in terms of simplicity and style and character.”

They say that in Hollywood nobody knows anything, but John Barry understood more than most about the art of the soundtrack. “I think most good scores to some degree go against the picture, or give another dimension to the picture,” he said in 1997. “That other dimension is what I always strive for.”

John Barry (John Barry Prendergast) 3 November, 1933 - 30 January, 2011

Watch a tribute to John Barry below

Add comment