London Sinfonietta, Adès, Queen Elizabeth Hall | reviews, news & interviews

London Sinfonietta, Adès, Queen Elizabeth Hall

London Sinfonietta, Adès, Queen Elizabeth Hall

Gerald Barry makes a silk purse out of a sow's ear

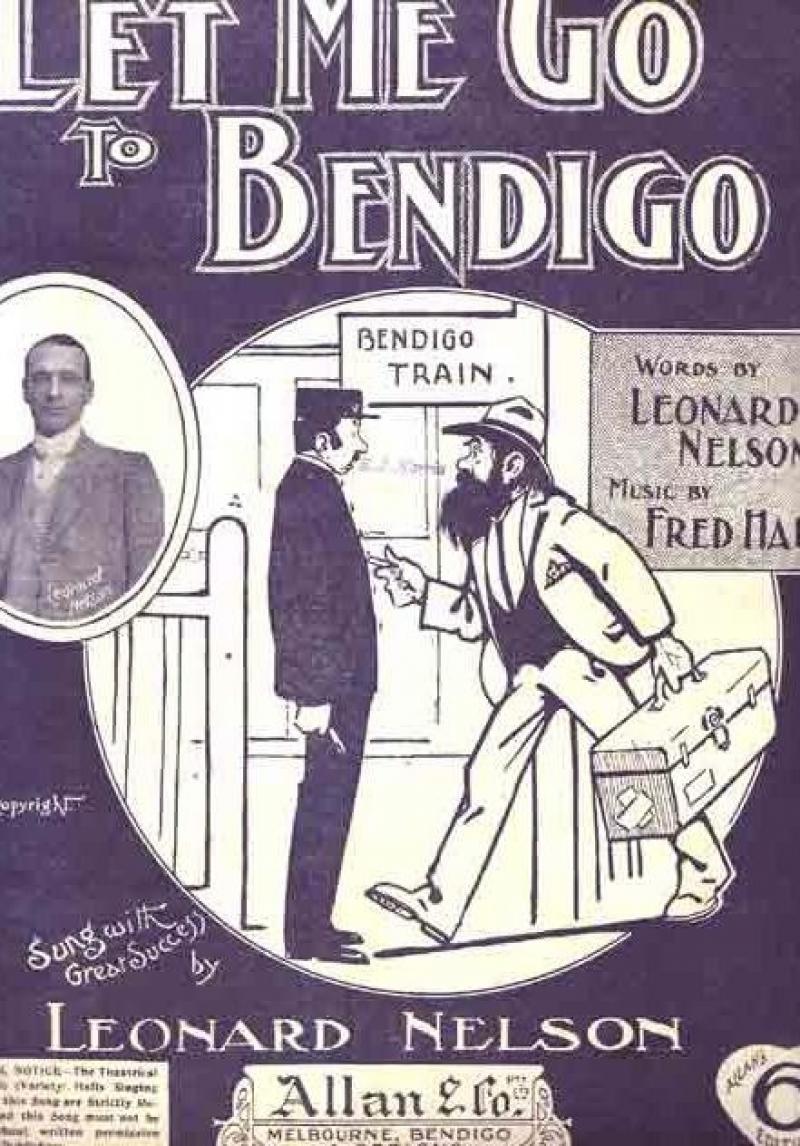

Like so much fine music, Gerald Barry's new work began life as detritus. Feldman's Sixpenny Editions, which received its world premiere at the Queen Elizabeth Hall last night, are elaborations on the tacky little Edwardian jingles whose browning dog-eared scores are still to be found in music shops up and down the land selling in big plastic buckets for 5p.

Unusually for such a seemingly sly, postmodern revelling in fluff, there's very little direct pastiche or wink-wink nudge-nudging. All is delivered with love and sincerity. Home Thoughts for solo piano sees pianist Huw Watkins bashing chordally through every register of the keyboard like a boy who's had too many sweets. Trombone and trumpet chase chamber orchestra and piano in A Bumpkin's Dance as if cops and robbers in a silent movie. And we end on an idle contrapuntal runaround of The Innermost Secret that felt like we were chasing a dozy bee through a garden.

There's a crush of musical allusions. But we are most close to the world of the 1970s British experimentalists: Howard Skempton, Cornelius Cardew and Christopher Hobbs. "I've always been fond of grey fugues and exercises and still play boring exam pieces with pleasure," Barry writes. "I go into a kind of trance playing them, tunnelling to the heart of dullness." The joy of Feldman's Sixpenny Editions, like the joy of a grey fugue, a Skempton miniature or a good game of Patience, is in the concentration and intensity that it elicits in all those participating (which included the ever-conscientious London Sinfonietta under the baton of Thomas Adès).

It all put me in mind of the paintings of Chardin (pictured right), with their obsessive attention to moments of intensely absorbing ordinariness, where a man might build a house of cards, a girl blows a bubble, a woman stirs a cup of tea. All that is considerable, Jonathan Miller once said, can be found in the negligible. There is something very considerable and infectious about Barry's commandeering of negligibility - as there was in his equally deceptively modest little opera La plus forte that was premiered in the UK last year.

It all put me in mind of the paintings of Chardin (pictured right), with their obsessive attention to moments of intensely absorbing ordinariness, where a man might build a house of cards, a girl blows a bubble, a woman stirs a cup of tea. All that is considerable, Jonathan Miller once said, can be found in the negligible. There is something very considerable and infectious about Barry's commandeering of negligibility - as there was in his equally deceptively modest little opera La plus forte that was premiered in the UK last year.

The rest of the programme celebrated the harp, and proved that not everything negligible is considerable. Per Nørgård's Second Harp Concerto (receiving its UK premiere) came across as considerably negligible. His idiosyncratic musical language, which hovered between a fragrant and failed state that had harpist Helen Tunstall engaging in both buzzy detachment and legato meanderings, was rarely marshalled to any great effect.

Much more dramatic and musical oomph was to be had from Thomas Adès's short early piece, The Origin of the Harp, for small ensemble, which seeks to summon up the sound of a harp from every instrument but the harp. Luciano Berio's immensely attractive Chamber Music, for clarinet, cello, soprano and a motoric harp, opened the evening, with its evocative and distinct settings of three James Joyce poems, sung with great magic by Allison Bell. Running between all these pieces were kora improvisations from Tunde Jugede, which were perhaps there to provide a bridge between the harp music and Barry's Minimalist fragments. I merely exploited the entrancing simplicity of Jugede's performances, using them like hot towels to clear my mind of the messier and, dare I say it, more engaging dramas that swirled around him.

- The London Sinfonietta season continues tonight at Symphony Hall in Birmingham

Find the music of Gerald Barry on Amazon

Find the music of Gerald Barry on Amazon

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Add comment