Brains: The Mind as Matter, Wellcome Collection | reviews, news & interviews

Brains: The Mind as Matter, Wellcome Collection

Brains: The Mind as Matter, Wellcome Collection

Sliced, shrivelled, diced or scanned, the brain is a marvel to ponder in this fascinating exploration

The mind is a beautiful mystery. We think, therefore we are. But how is the mind and physical body related? How does a lump of matter give rise to consciousness? Naturally, it’s a question that’s exercised great minds over many centuries, and will, I’m sure, continue to do so for another few. Unsurprisingly, you won’t find any answers in the Wellcome Collection’s spectacular exhibition, Brains: The Mind as Matter.

Divided into four sections, each of which are pretty self-explanatory – Measuring/Classifying, Mapping/Modelling, Cutting/Treating and Giving/Taking – the exhibition takes a historical overview that explores the radical interventions the brain has been subjected to in the name of investigation, treatment and cure.

We find tree-like branches and roots and tissue strata, and marvel at such replications in nature

That overview begins with a reminder of how little the brain meant to the ancient Greeks. Aristotle famously disregarded it as the seat of consciousness, claiming the heart and the liver as the twin seats of consciousness and emotion. By the time of the Roman Empire, however, a consensus was reached that the brain was indeed the engine room of consciousness, whilst Galen, the second-century physician/philosopher, identified the ventricals, the brain’s fluid-filled cavities, as the location for the faculties of reason and memory.

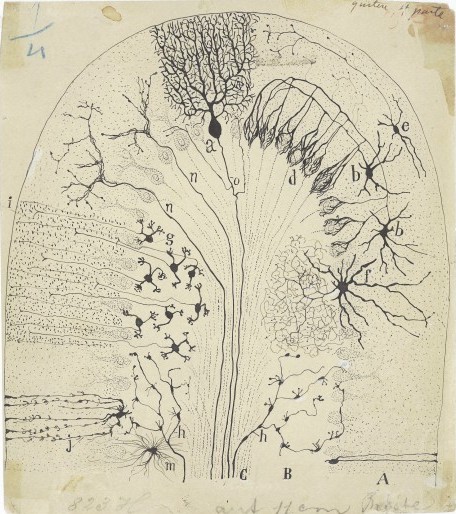

As we cover each relevant section, the exhibition provides an overview of the disputed territories of the brain, and thence to epic moments in the history of neuroscience. We encounter the work of the father of modern neuroscience, the Spanish Nobel Prize-winner Santiago Ramón y Cajal, whose pioneering research at the turn of the 20th century gave us an understanding of the microscopic structure of the brain. Having displayed an early talent for drawing and painting, Cajal had longed to train as an artist, but his father had insisted he follow the family tradition into medicine.

As we cover each relevant section, the exhibition provides an overview of the disputed territories of the brain, and thence to epic moments in the history of neuroscience. We encounter the work of the father of modern neuroscience, the Spanish Nobel Prize-winner Santiago Ramón y Cajal, whose pioneering research at the turn of the 20th century gave us an understanding of the microscopic structure of the brain. Having displayed an early talent for drawing and painting, Cajal had longed to train as an artist, but his father had insisted he follow the family tradition into medicine.

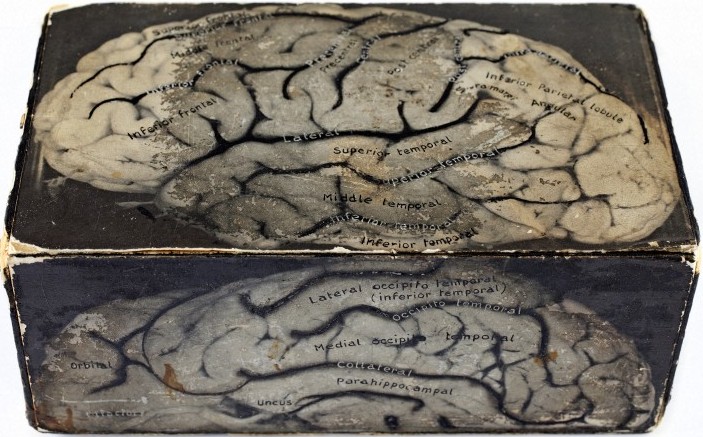

Cajal’s intricate drawings of the brain’s cellular structure show the hand of an impressive draughtsman – he made thousands of drawings on any scrap of paper he could find, accurately describing the brain’s complex circuitry (see picture above, drawing 1894; bottom: box model of the brain, mid 20th century, University of Aberdeen). In these beautiful, sinuous depictions, which suggest a beguiling “garden of neurology”, we find tree-like branches and roots and tissue strata, and marvel at such replications in nature.

Inevitably we encounter a fair share of quackery as well as wrong turns, blind alleys and theories that are, with perhaps depressing inevitability, used for grotesquely inhuman ends. A heartbreaking section dwells on the thousands murdered in German clinics and mental institutions during the Nazi era as the theory of eugenics was taken to what some might argue its logical conclusion. There are letters to mothers telling them that their children had died of pneumonia, when, in fact, they had been starved or gassed or had been given drug overdoses, their brains subsequently harvested, preserved and examined by respected neuropathologists who went on to continue their eminent careers long after the end of the war.

Inevitably we encounter a fair share of quackery as well as wrong turns, blind alleys and theories that are, with perhaps depressing inevitability, used for grotesquely inhuman ends. A heartbreaking section dwells on the thousands murdered in German clinics and mental institutions during the Nazi era as the theory of eugenics was taken to what some might argue its logical conclusion. There are letters to mothers telling them that their children had died of pneumonia, when, in fact, they had been starved or gassed or had been given drug overdoses, their brains subsequently harvested, preserved and examined by respected neuropathologists who went on to continue their eminent careers long after the end of the war.

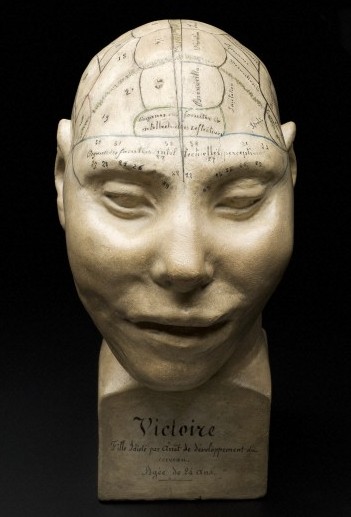

It’s also astonishing to discover that the British Phrenological Society was only dissolved in 1967. It was Franz Joseph Gall, the German neuro-anatomist, who founded phrenology in the late 18th century. His theories were to have a profound influence on the Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso, whose cruder methods of measuring the shape of the skull were used to distinguish between the normal and the morally degenerate. Whilst Cajal was making his pioneering discoveries into the internal structure of the brain, these theories were being widely disseminated in England by figures such as the British psychiatrist Bernard Hollander. We see models of phrenological heads (pictured above: phrenological head, c 1825) and various implements that measure the skull and that were used by the British on colonial populations in gathering anthropometric data, sometimes with brutal force.

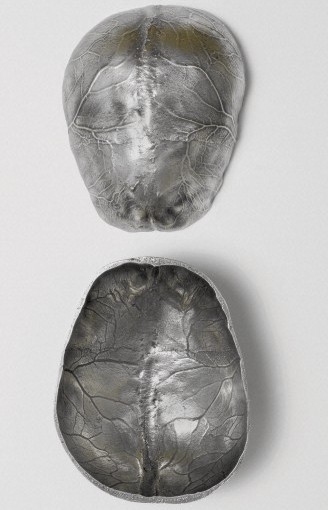

There are some wonderful contemporary artworks dotted throughout, including Katherine Dowson’s captivating My Soul, a “floating” gossamer-like 3D representation of the artist’s brain, laser-etched into two blocks of crystal glass (main picture); and Annie Cattrell’s two silvered bronze casts (pictured left) which show an impression of the brain on the interior surface of the skull – the cabbage-like veins weaving a fine web across the cool metal surface.

There are some wonderful contemporary artworks dotted throughout, including Katherine Dowson’s captivating My Soul, a “floating” gossamer-like 3D representation of the artist’s brain, laser-etched into two blocks of crystal glass (main picture); and Annie Cattrell’s two silvered bronze casts (pictured left) which show an impression of the brain on the interior surface of the skull – the cabbage-like veins weaving a fine web across the cool metal surface.

Of course, the brain itself isn’t much to look at: that sliver of Einstein’s brain enmeshed in a slide, or that fraying fragment of a lump that once belonged to infamous body-snatcher and serial killer William Burke, or that mummified central hemisphere belonging to an ancient Egyptian, or indeed the segment of brain with a bullet lodged in it. But sliced, shrivelled, diced or scanned, it’s certainly a marvel to ponder.

- Brains: The Mind as Matter at the Wellcome Collection until 17 June

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment