Ballet Meets Science | reviews, news & interviews

Ballet Meets Science

Ballet Meets Science

Scientific giants Einstein and Darwin inspire two dance premieres at Rambert and Birmingham Royal Ballet

Two ballets are premiered this month with big scientific subjects and new commissioned scores. Birmingham Royal Ballet's David Bintley was inspired by Einstein's principle of relativity, with a Matthew Hindson score, while Mark Baldwin at Rambert Dance Company has been excited by Darwin, with a Julian Anderson score. How does science meet dance?

Einstein+Birmingham Royal Ballet: e=mc2 by David Bintley

ISMENE BROWN: How do you think science connects with dance?

DAVID BINTLEY: Really I was looking for a subject to work on with the particular composer, Matthew Hindson. I came across Matthew a few years ago, heard his music, met him at a premiere of a flute concerto in London, and we got on really well. Quite a lot of choreographers had used his work and his music is intensely danceable. This is a big orchestral score - his second symphony, which is being premiered. There's a large percussion section, the middle movement has a nice principal violin leading role, and there’s some electronics, a sort of collage which he made with a sound engineer. A lot of his work has a technological background.

I happened to reach this marvellous book by David Bodanis, E=mc2: A Biography of the World’s Most Famous Equation. The whole thing is really a history of the science behind the equation and how Einstein reached it. So it starts 2000 years ago and goes up to the present and beyond. What impressed me was that it was a whole history of man and a whole history of science behind this great discovery. There are so many facets to it - it’s not a dull old formula. It explains everything in the universe.

I wrote to Matthew and said, “Read this book, is there something here?” I said I want to do a piece on it, like a symphony, with each element of the equation featured. The first movement is Energy, the second Mass, the final movement is Speed of Light or c2, and there’s an interlude called The Manhattan Project, which was the atom bomb. The titles enough suggest movement to me - aside from that, there is in the background all of the reading that I’ve done over the past couple of years just to inform me as much as I can.

But having said that, this is not a learned piece - I’m not a scientist, I can’t even claim to really understand it. but I think that’s part of the charm of it. It’s so elusive, this world, that it is beyond ordinary people. Part of the charm is the mystery, and the humour too. Because even scientists say, “We don’t know everything and we probably will never know.” For instance light behaves in two ways, like a particle and like a wave. And if you observe a light photon behaving like a wave it will stop and behave like a particle. Which seems to me completely hilarious.

Are there animations you can see of this? I mean, computer models?

It’s highlighted every time you look in a piece of glass. About 90 percent of the photons go through it, about 10 percent come back giving you a reflection. There is no way of telling which photons will go through and which will come back. Everything is made of atoms, and largely they’re empty. If you took the entire human race and took out all the emptiness, we would all fit on a teaspoon. We are actually basically hot air!

We are actually basically hot air!

We are nothing. We are made of nothing - 99 percent of everything is nothing. And there’s a lovely description in one of the books I read which said, if you’re talking of size, that’s the equivalent of a moth in St Paul’s. That emptiness and loneliness is something I tried to capture in the "Mass" movement. (Picture, left, by Roy Smiljanic for BRB.)

So it’s the metaphors that attach themselves to science that give you the bridge into dance?

Yes. Nothing but that. David Bodanis said himself that watching this dance he gets the awareness of the equation. It’s not going to tell physicists anything. it’s not going to explain the world. It’s more poetic, hopefully.

Visually how are you treating the presentation?

We have no scenery as such, costumes are spare, and what I tried to do it do it with light. The lighting designer is Peter Mumford.

Have you tried to choreograph the light with him? It affects perception of dance so much.

From the beginning I said to him I had ideas of certain effects I wanted. And I think we’re being inventive with it. We’re using the light and how we move in and out of it. But there again, I would stress that this is a piece that for me is really stripped down. I wanted to challenge myself, so it is very spare in terms of theatricality. The dance language of the piece has concerned me primarily. i’ve spent a lot of the past years dealing with narrative. Here I’ve been trying to mirror what is quite a complicated score.

Do you want a dance language that seems “scientific”?

I’m looking for a language that is peculiar to this piece. But clearly if you’re doing a movement based on all notions of energy, from electromagnetic and static, from Big Bang to heavy machinery, that’s a pretty open field. There are all sort of ideas you can glean from that. It is by and large ballet language, I don’t get far away from that. I would do it completely differently from Wayne McGregor, for instance, but I think it brings out invention within the field I work in. I have been trying to introduce elements which perhaps I haven’t used before. I’ve been trying to find a different kind of beauty... if that makes sense. Because while we think of symmetry and harmony, which ballet does very well, I’ve tried to find a different kind of symmetry and harmony.

Have visual materials helped you at all?

I was certainly looking at those fantastic pictures from the Hubble telescope of nebulae. The Horsehead Nebula is one of the most indescribably beautiful things, and there’s one lift in Mass which is intended to convey that size and grandeur. Yes, the unusual shapes of nebulae certainly I’ve tried to evoke in the second movement. That one is a triple trio. Again, it took me a long long time to arrive at that structure, and I needed a sizable group to arrive at the shapes I wanted - the nebulae, those fantastic star clusters, which make shapes that are almost human.

Your choreography, I would say, is by nature very human, warm - is it a challenge to be coolly scientific?

No, Einstein said imagination is more important than knowledge. He played Bach on the violin, he believed somebody made the whole thing - if not God - and he was a comedian. When Robert Oppenheimer dropped the bomb he quoted the Bhagavad Gita. Maybe science is dull to people sitting in classrooms, as I was once, but I don’t think science is dull at all to the people who do it.

Birmingham Royal Ballet's new triple bill 'Quantum Leaps', which includes E=mc2, is now at Birmingham Hippodrome until Saturday. Book online here. Then tours to Plymouth, Sunderland and Sadler's Wells. Information here

Darwin+Rambert: Comedy of Change by Mark Baldwin

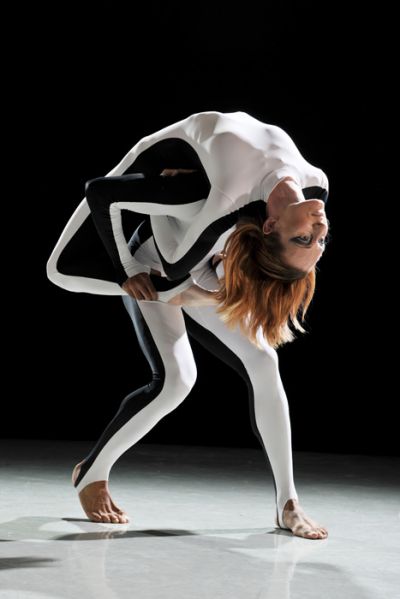

MARK BALDWIN: I suppose everything’s science. I did biology at uni for a couple of years and there’s always been a science thing about everything I do, going way back to when I was the first person in Britain to learn to use a computer to choreograph on. They’re not that far apart at all. In fact the art of how to move the body in space and time is a kind of science. People can use that movement to tell stories or just to be what it is. Because dance uses the natural body I don’t find it at all weird to link science and dance - I find it an unbelievably easy marriage. This particular piece has been the most beautiful journey I’ve done. (Photograph, right, of Comedy of Change by Hugh Glendinning for Rambert).

It started with something Stephen Keynes, my friend for about 30 years, came up with. His mother’s father was Darwin’s son - he’s the great-grandson. He’s also nephew of John Maynard Keynes, so the ballerina Lydia Lopokova of course was his auntie. He made the suggestion that we do a piece to commemorate the Darwin year, 2009 - he originally hoped all the big dance companies would do something.

But the big introduction was to Professor Nicky Clayton, who’s Professor of Cognition at Clare College, Cambridge, because when she’s not being a professor she teaches salsa and tango four nights a week. In fact she’d do it seven nights a week if she could, she’s a fanatic.

Nicky gave us a little lecture about Darwin, evolution and her field, which is birds. How birds over a long time have come up with these amazing dances, for sexual selection. And in nature it’s often about female choice in some of the birds, which is why for instance the males of the Blue Mannikin from South America and the Bird of Paradise in New Guinea have incredibly elaborate dances.

Nature has brought about this evolution of amazing dances. The reason is that over time the female birds have got fussier and fussier. And because food is so common on the forest floor, these guys spend 80 per cent of their time practising their dancing. So if their footwork isn’t precise and their headwork isn’t perfect, the female gets bored and wanders off. If you look at film of the Bird of Paradise, you see they even fluff out their feathers around their legs that look like tutus.

The Mannikin birds dance in pairs. There’s always a fabulous male who always has an apprentice with him - the females won’t look at him unless he ‘s got one with him. So the males present themselves as a couple to the female. Nicky found this relationship with tango, Argentinian tango, which was originally for men together. You can be dancing with someone and flirting with someone else at the same time. So I stole some of the dances from nature.

These birds' relationship of male to female completely changes the normal relationships human beings strike by habit on stage.

Yes, precisely. And I wanted to relate us to the animal world - we are animals, and they scamper, they flick their spines, they leap, they’re clumsy. We all started out as bacteria and over millions of years all came into these astoundingly different species. But it is, after all, a dance piece. It flows in endless metaphors.

Why did you ask Julian Anderson to do the music?

John Drummond left me some money to commission a piece of music especially for dance. There’s also something called the John Drummond Fund, just for doing that. He introduced Julian to me years ago and we did a work called The Bird Sings With its Fingers together a while ago. This Darwinian theme is a subject he’s really interested in, because his father was one of the people who came up with the idea of how to photograph viruses or bacteria by staining them. If you look at our poster, the really early one we had to have made, they’re dancing around in a sort of fug - which is a flu virus, blown up and stained yellow and red.

Julian has written a piece in seven movements. The first is two minutes long, and him being clever he’s tried to squeeze 20 million years into two minutes. The movement I like is the fifth, which is very Stravinskyish, and it plops, pongs and pings. It’s really sharp, and it’s kind of about display.

You made a previous dance with a physics theme for Einstein’s year, 2005, called Constant Speed - has this one felt different in the making?

I knew more about this one from my biology studies at uni. In terms of evidence I had to learn all about the physics stuff. Scientists are fiercely competitive - they only do leaf shape, or fungus in wheat, or bacteria of some specific kind. They love their own areas, but what brings all these people together is evolution and change. So the piece changes gradually all the way through, there’s a visual evolution.

How did you set about the visual staging? You're working with the artist Kader Attia.

I don’t know if you saw Versace ads in the last few months, but Kader did an installation for that of hundreds of praying women made out of silver paper, apparently praying or bowing in adoration. It’s a Darwinian idea that humans have always looked for leaders, and tried to create gods. So the dancers construct one, while they’re at it. For me probably my favourite moment is when they’ve built this figure and it becomes a sort of fossil, a ghost of the part. It took quite a while to boil it down. Kader kept asking for suggestions from the costume designer, Georg Meyer-Wiel, who was a taxidermist by training, then went to the Royal College of Art to study theatre design, so he’s both theatre designer and a taxidermist. He has a huge collection of stuffed birds, thousands of different bird feathers.

How did you find Georg?

When I first came to Rambert he graduated from the RCA and brought me his portfolio. It was quite difficult for him because Kader is the production designer, and Georg has to serve that purpose, so Kader kept ordering suggestions for things, and we came up with these broad ideas for chrysalises, costumes with bones, or the original very elaborate costumes which had huge headpieces like something from Alien, with amulets like pods which would cost £3,000 each. Then we went to a meeting in Berlin where Kader lives, and spent six hours boiling the whole lot down to a very extreme, simple and beautiful look.

It was painful! I was quite happy that working with visual artists you’ve got to give up control of some kind or there’s not point having them on board. Georg was saying, “But there’s nothing of me left!” And Kader was explaining to him that this is about what we’re all doing together. Not about you or him or me. And it’s Diaghilev’s year, so we had to meet that idea of the eternal triangle between dance, art and music. So we came back to London exhausted, but I was happy that we had something that on stage would find its own beauty because it was so simple.

Watch Rambert rehearsals on Sky Arts here

Rambert performs Comedy of Change at The Lowry, Salford (tonight, tomorrow). Book online here. It then tours Nottingham, High Wycombe, Shrewsbury, Poole, Sadler’s Wells, Bath, Norwich and Northampton. Comedy of Change microsite

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Comments

...