2001: A Space Odyssey with live score, Philharmonia, de Ridder, Royal Festival Hall | reviews, news & interviews

2001: A Space Odyssey with live score, Philharmonia, de Ridder, Royal Festival Hall

2001: A Space Odyssey with live score, Philharmonia, de Ridder, Royal Festival Hall

Young conductor excels in tricky film synchronisation - Viennese waltz included

Imagine a special two-hour-plus resurrection of that wannabe extravaganza Stars in Their Eyes.

Let me try and explain what I mean by de Ridder "being" Karajan. I'd completely forgotten as I absorbed once again this perfect aural equivalent to the weightlessness of space what recording Kubrick had originally used as he moves from his opening sequence of apes, tapirs, tools and monolith to modern man in orbit (half an hour passes, incidentally, before a single word is spoken). Yet as our present team glided languorously through the central strain of Johann Strauss the Younger's most famous waltz sequence, I found myself thinking that the only equal to this blissful, expansive freedom of phrasing was the greatest Viennese New Year's Day performance of them all, Karajan's Vienna Philharmonic Emperor Waltz. And this, as it turned out, had to be something of a Karajan impersonation to fill the right amount of time. But de Ridder wasn't conducting along to the Berlin Philharmonic soundtrack (reproduced below in the first part of the film's Blue Danube sequence) in an earpiece; all he had was a time machine, as it were, counting down to cut-off point, and a sense of deep rubato which sprang from his own flexible technique, not an impersonation of the master.

Watch a clip of the Blue Danube sequence in Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey

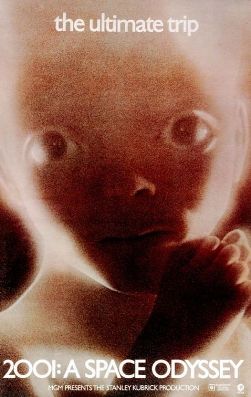

In a way, the waltz king's number was his biggest challenge, and one he was able to relax into as the band played on once more beyond the closing credits. For de Ridder, more complicated scores may seem like childsplay: I'll never forget the incisive results he got with an ad hoc band in Prokofiev's hideously difficult score for The Gambler on little rehearsal at Grange Park Opera. And here he was making light of complexity as he plunged his sensuous Philharmonia strings into Hungarian maverick-genius Gyorgy Ligeti's Atmosphères, serving as orchestral prefaces to the two parts of the film in addition to its later incorporation. Later the highly professional choir of the Philharmonia Voices layered their sound just as impressively in Lux aeterna, joined at one point to the music of Ligeti's Requiem for the psychedelic trip which forms the climax of the movie.

In the filmic placing of all these extra-terrestrial sounds, Kubrick's genius resounds. One of his many idiosyncratic moves in 1968 as he translated Arthur C Clarke's sci-fi tale into a slice of cinema we still can't dismiss, whatever we may think about certain aspects of its ambitious scope, was to incorporate as his supernatural bedrock scores by Ligeti which had only struck open ears with their novelty a few years earlier in the decade. Having picked and mixed his soundtrack from various sources, the director could not have imagined how they would pose potential problems for a live, top-notch choir and orchestra over 40 years later. Not that the difficulties were apparent for a moment here, though I suspect some members of a young and curious audience may have been a bit taken aback, perhaps accounting for the barrage of coughing after the first bout of Ligetian atmospherics which greeted the sunrise prelude proper, the first 58 seconds of Richard Strauss's Also sprach Zarathustra.

What a treat of an introduction to the orchestra for any who hadn't experienced it like this - and let's not leave out of the list another gravity-free movement, the Adagio from Khachaturian's Gayaneh ballet, which was perhaps Kubrick's most outlandish choice. It marks the change of mood as a second space mission heads towards the mystery of a 25-million-year-old monolith found on another moon, and for the first time we hear a collage of voices and music (as Gayaneh rolls on, one of the young astronauts' parents beam him up "Happy Birthday" from Earth in one of many televisual moments that have more or less come to pass).

Is it pretentious? I don't know, and I didn't care as I succumbed again for the first time in decades to the cinematic storytelling and the underlying concern for the human predicament. Kubrick has a symphonic sense of light and shade, gravity and weightlessness; he builds the greatest tension in sequences where there isn't any music at all, only the heavy breathing of the men in spacesuits and the insidious drawl of the semi-comic computer villain HAL. We may occasionally laugh at the 1960s fashions applied to futuristic vision, ape masks which don't quite complement the scary noises (and would have been better done by animal magic man Rostislav Doboujinsky) and Leonard Rossiter as a suspicious foreign scientist with a very dubious accent. Yet the trippy denouement still works, at least when seen on as big a screen and in as flawless a print as this. Conducting monotonous Philip Glass to old movies is a doddle; synchronising Prokofiev to Eisenstein is a step much higher on the ladder; but perhaps this was the toughest mission yet, and all the performers accomplished it with flying colours.

Is it pretentious? I don't know, and I didn't care as I succumbed again for the first time in decades to the cinematic storytelling and the underlying concern for the human predicament. Kubrick has a symphonic sense of light and shade, gravity and weightlessness; he builds the greatest tension in sequences where there isn't any music at all, only the heavy breathing of the men in spacesuits and the insidious drawl of the semi-comic computer villain HAL. We may occasionally laugh at the 1960s fashions applied to futuristic vision, ape masks which don't quite complement the scary noises (and would have been better done by animal magic man Rostislav Doboujinsky) and Leonard Rossiter as a suspicious foreign scientist with a very dubious accent. Yet the trippy denouement still works, at least when seen on as big a screen and in as flawless a print as this. Conducting monotonous Philip Glass to old movies is a doddle; synchronising Prokofiev to Eisenstein is a step much higher on the ladder; but perhaps this was the toughest mission yet, and all the performers accomplished it with flying colours.

- One more "live screening" of 2001: A Space Odyssey at the Royal Festival Hall on Friday 8 April

Find Stanley Kubrick on Amazon

Find Stanley Kubrick on Amazon

Buy

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment