Rona Munro on writing Little Eagles | reviews, news & interviews

Rona Munro on writing Little Eagles

Rona Munro on writing Little Eagles

The RSC playwright explains why the Space Race is still relevant today

My latest play, Little Eagles, marks the 50th anniversary of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s first orbit around the Earth. Gagarin’s place in history is, quite rightly, assured but little is known about Sergei Korolyov, a brilliant engineer and the chief designer of the Soviet space programme. Koroloyov may not have won the race to put a man on the moon, but he was responsible for a series of extraordinary firsts in the space race, including the first human in space.

In 2007 the Royal Shakespeare Company told me they were looking for contemporary writers to write big history plays – which are, of course, very much part of the Shakespearian tradition. At about the same time there was a serendipitous flutter of articles about the Apollo moon missions and I vividly remembered what a huge part of my childhood they had been and how they had shaped what I thought the future would be like. Looking back, it is astonishing to realise that only 12 men have actually walked on the moon. All of them are elderly now and some of them are already dead. The world I'd thought would be my future has become history. I realised this was the history I wanted to write about.

My original idea was to write a play about the Apollo missions. The history of the American space missions, from Mercury to Apollo, is utterly gripping. Hundreds of books and films exist on the subject and they only scratch the surface. I found stories I remembered as news broadcasts and live TV events that had us all glued to the TV in the Sixties and I found others I'd never heard about - apparently NASA seriously considered a number of women astronauts in the early years of the space race but got cold feet at the last minute and pulled them out of the programme. However, in the middle of all this research (and the research is the really fun and exciting part of writing, especially with a subject like this), I thought I ought to just check what the Soviets were up to during the same period. What I found out was just off-the-scale astonishing to me.

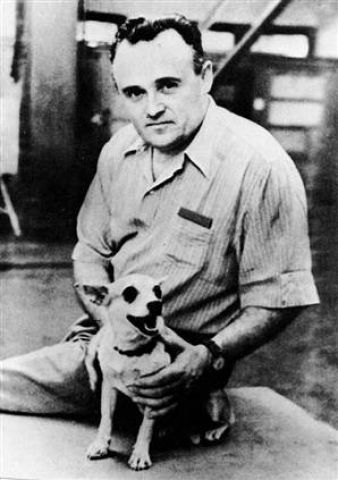

I'm not certain why this history, the story of Sergei Korolyov (pictured below) and his team is so little known. Of course during Korolyov's own career his identity was a closely guarded secret and he was only known as the mysterious “Chief Designer”. I also think, when the Iron Curtain came down, as the space race was long over, there wasn't the same interest in its history or its heroes. However, what I seemed to be learning was that this one man was not just the architect of the Soviet space programme, he'd been the instigator of the whole dream of pushing humanity beyond the Earth. If he had not launched Sputnik, the world’s first satellite, the whole race to escape gravity might never have begun. I'd found my hero but I still had a long way to go to shape the play.

It was at this point I was able to take advantage of the relationship the RSC had with Davidson College, a university in North Carolina. In the past they had taken over full Shakespearean productions to Davidson but in 2008 it was decided to do something a little bit different and take over a piece of new writing to be developed in workshop. We had a gigantic rough first draft, a team of fabulous actors from Britain and the States, myself, director Roxana Silbert and a mad keen chorus of students.

It was at this point I was able to take advantage of the relationship the RSC had with Davidson College, a university in North Carolina. In the past they had taken over full Shakespearean productions to Davidson but in 2008 it was decided to do something a little bit different and take over a piece of new writing to be developed in workshop. We had a gigantic rough first draft, a team of fabulous actors from Britain and the States, myself, director Roxana Silbert and a mad keen chorus of students.

There followed an insane two weeks work in which this huge history including World War Two, female astronauts, Yuri Gagarin, gulags, missiles and men on the moon had to be squashed into one play to be presented, script in hand, in front of an alarmingly large audience. There were some fantastic moments and some truly staggering performances but the thing ran at over three hours and it was all just too much. But there was nothing I could bear to cut.

When I came away from that experience and took a deep breath, I realised I was trying to tell three stories – the Apollo missions, the women astronauts and Korolyov’s story. So I made a rather ambitious decision. I needed to write three plays. Little Eagles is the first of what I hope will be a trilogy. The second one will be about the women astronauts and has already been commissioned by Plymouth Theatre.

A history play is, by definition, epic. The story is large but, you often have to simplify and condense events to allow them to play as drama. There is also the added complication that you are writing about events and people that actually existed. Several of the characters in Little Eagles are still alive and I had to make my peace with how I felt about that. At the end of the day I do trust audiences to have the intelligence to understand that they are watching a piece of theatre and not a documentary. I think my job as a writer is to write a good piece of drama, a story that is about universal human experience as much as about any specific individual - we don’t assume that we know what Henry V was really like but we do want to go and see a play about a character with that particular history.

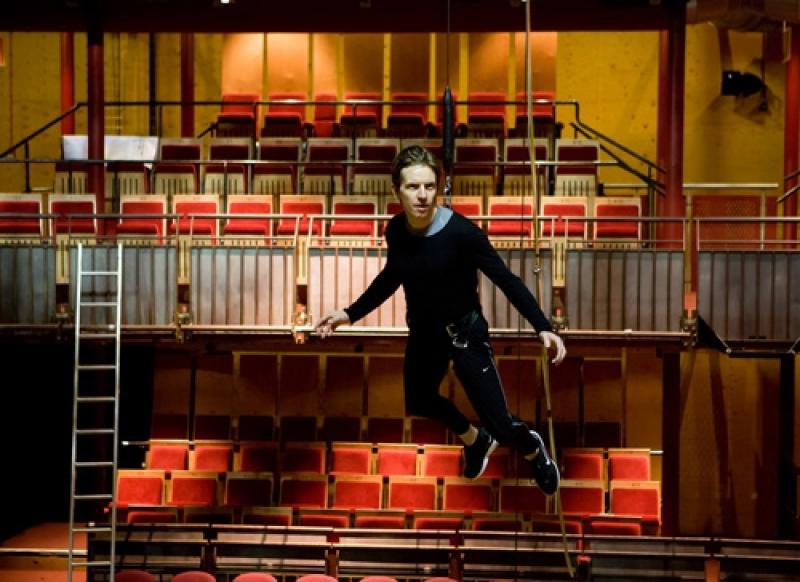

I also had to try and find a balance between the human interest and the factual, scientific part of the story. My own woeful inability to understand the hard science was probably an advantage there. There was no risk I was going to bamboozle a lay audience with rocket science because I can barely hold the science in my head long enough to get it on the page. For me it was a laborious process of constantly reading and re-reading to check that I hadn’t said anything incredibly stupid and then, once I’d reassured myself it made sense, I promptly forgot it. It’s like that part of my brain can’t retain the information - I can just grasp the concept for the two or three minutes it takes to go, “Oh no, he can’t say that about the fuel injection,” and then it’s gone again. Probably that's partly why I was drawn to the subject in the first place - scientists, academics, people who can harness that sort of information and use it just seem jaw-droppingly impressive. With a big play like Little Eagles and a company like the RSC you do hope you might get a bit of spectacular theatricality. However, I always try and write in such a way that, in the worst case scenario, if a play had to be performed in a bare space with no embellishments of any kind, the story would still work. I actually think that’s the most exciting kind of theatrical writing because instead of just passively sitting there, the audience has to bring their own imagination to the piece – of course, if they don’t feel inclined to do that, you’ve got a hideous flop on your hands but if they do, it’s just electric and that’s what makes theatre so exciting. (Pictured above: Dyfan Dwyfor rehearsing as Yuri Gagarin. Photograph by Lucy Barriball.)

With a big play like Little Eagles and a company like the RSC you do hope you might get a bit of spectacular theatricality. However, I always try and write in such a way that, in the worst case scenario, if a play had to be performed in a bare space with no embellishments of any kind, the story would still work. I actually think that’s the most exciting kind of theatrical writing because instead of just passively sitting there, the audience has to bring their own imagination to the piece – of course, if they don’t feel inclined to do that, you’ve got a hideous flop on your hands but if they do, it’s just electric and that’s what makes theatre so exciting. (Pictured above: Dyfan Dwyfor rehearsing as Yuri Gagarin. Photograph by Lucy Barriball.)

I had always assumed – wrongly as it turned out – that Little Eagles would go on in one of the RSC’s spaces so I wrote it so that it could be done in the round with a minimal set. There’s quite a subtle difference writing in the round as opposed to an end-on space. With in the round you can overlap scenes and the way in which you can have one set of action flowing into another is exciting and dynamic - but now we’re doing it in the Hampstead Theatre end-on, so I’m very grateful to be working with Ti Green, who is a brilliant designer, and Roxana who, between them, have managed to make the staging work.

This is my fifth outing with Roxana and it’s a delight because she does what I think all good directors do, and that is to act as a communicator between the text and the cast. Ultimately it’s a dialogue that starts with you and the director, then the director takes it to the cast and then the actors take it to the audience. It’s a very active relationship. I was lucky enough to get the chance to work directly with actors right at the start of my career through the Edinburgh Playwrights Workshop. They were a collective of writers and actors who, at that time, would give readings of any script that was sent to them. I think that experience gave me a real understanding of how dependent you are, as a writer, on what the actor brings to the script and to an audience. It also gave me a real chance to see the stories you could tell an audience with no staging at all, so if anyone was to ask me what experience has most informed the work I'm doing now I'd have to say that was it.

I think that there are several things that make Little Eagles relevant today. The first, which is a constant, is that it shows the tragic drama of a huge dream. One person’s ambition can achieve so much, but there are always consequences, for the world and for that one person. That's been true of so many great men and women throughout history. What Korolyov wanted more than anything was to take mankind into space, but his rocket technology also powered missiles and his dream killed some of the cosmonauts - his little eagles - and ultimately cost him his own life. (Rona Munro pictured right)

I think that there are several things that make Little Eagles relevant today. The first, which is a constant, is that it shows the tragic drama of a huge dream. One person’s ambition can achieve so much, but there are always consequences, for the world and for that one person. That's been true of so many great men and women throughout history. What Korolyov wanted more than anything was to take mankind into space, but his rocket technology also powered missiles and his dream killed some of the cosmonauts - his little eagles - and ultimately cost him his own life. (Rona Munro pictured right)

However, whatever your opinion of the Space Race and all its implications - the huge amounts of money it gobbled up, the Cold War, armaments - there was something heroic about it. When both the Americans and the Soviets first set out to put a man on the moon it was utterly impossible – it really was a dream. But eventually two guys with a tiny little vessel hardly thicker than tin foil and a computer with less calculating power than a modern mobile phone, walked on the moon. Just think what could happen if we put the same energy and sense of purpose to curing cancer or preventing world hunger? Korolyov proved that, clearly, if we only put our minds to it, we are capable of achieving the impossible.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Add comment