The Queen: Art and Image, National Portrait Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

The Queen: Art and Image, National Portrait Gallery

The Queen: Art and Image, National Portrait Gallery

A bland and dispiriting exhibition of the most ubiquitously depicted person in history

The Queen is the first mass-media monarch, and still probably the most ubiquitously depicted person in history. Her 60 years on the throne is only exceeded by Victoria, and her reign has coincided, of course, with photography, film and television. The profusion of royal imagery is exaggerated and exacerbated by the cult of celebrity and the new technology of the internet and social networking.

The Queen however has, one way or another, escaped the worst excesses of the vitriolic glee that has accompanied criticisms of other members of her family. This exhibition charts a meandering journey from reverence (and even the hyperbole of a New Elizabethan Age) to a realisation of an expensive remoteness, to a dangerous irrelevance, a growing republicanism, anger, and finally to a kind of personal affection for the Queen herself, if not all the members of her extended family.

The exhibition has already visited the three other capitals of her fractiously united kingdom – Cardiff, Belfast and Edinburgh – and has not been compiled by courtiers, although we are given to understand that the royal household is pleased. And so they should be, for its fascination lies in its very impenetrability, in that Churchillian phrase, "a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma" – and protected by an overwhelming blandness.

This is not a sharp-eyed view, or an anthology with a cutting edge: the nearest we get is a small glass case, the contents of which show the extremes of royal imagery: stamps which feature the stylised official use of the royal image, and a couple of Private Eye covers with their mild frisson of anti-establishment public-school satire. But otherwise we are not given any sense of how the imagery has been used, from the royal household’s Christmas cards to the pages of the tabloids and the thousands of postcards. The catalogue (£20) does however contain analytical essays by the historian David Cannadine, also chair of the NPG trustees, and the clever curator, Paul Moorhouse, reproduces at least one image from Spitting Image, and offers a sharp chronology which unpretentiously charts the ups and downs of royal imagery in conjunction with the waxing and waning of royal popularity.

This is not a sharp-eyed view, or an anthology with a cutting edge: the nearest we get is a small glass case, the contents of which show the extremes of royal imagery: stamps which feature the stylised official use of the royal image, and a couple of Private Eye covers with their mild frisson of anti-establishment public-school satire. But otherwise we are not given any sense of how the imagery has been used, from the royal household’s Christmas cards to the pages of the tabloids and the thousands of postcards. The catalogue (£20) does however contain analytical essays by the historian David Cannadine, also chair of the NPG trustees, and the clever curator, Paul Moorhouse, reproduces at least one image from Spitting Image, and offers a sharp chronology which unpretentiously charts the ups and downs of royal imagery in conjunction with the waxing and waning of royal popularity.

What is dispiriting about the exhibition as a whole is the lack of any imaginative vision on the part of most of the artists, whether photographers or painters. The imagery becomes almost cloyingly repetitive, and much is almost unremittingly mediocre. Even the names seem defeated, with the Warhols (1985) prettily decorative, lifting banality to new heights without any ironic seasoning. The Annie Leibovitz photograph, taken in 2007 (main picture), costumes the Queen in an echo of the Admiral’s cloak that is such a feature of the 1955 Annigoni full-length portrait. Leibovitz sets her subject in what appears to be a piece of woodland about to be engulfed by an oncoming storm in a strained search for something new to say or show about her subject, and settles for a mindless melodrama.

Much is made of the fact that both the Annigoni full length of 1955 and 1969 are shown together for the first time: both are slick and icy, and the touch of melancholy that might have lifted the regal expression into something evoking empathy just looks as though Her Majesty were suffering from indigestion. The tiny Lucian Freud (pictured previous page) gives us the Queen looking cross, her face all rumpled up like a badly folded handkerchief, mildly ludicrous and wholly unconvincing.

Much is made of the fact that both the Annigoni full length of 1955 and 1969 are shown together for the first time: both are slick and icy, and the touch of melancholy that might have lifted the regal expression into something evoking empathy just looks as though Her Majesty were suffering from indigestion. The tiny Lucian Freud (pictured previous page) gives us the Queen looking cross, her face all rumpled up like a badly folded handkerchief, mildly ludicrous and wholly unconvincing.

The early and perhaps more straightforward practitioners of the royal genre, the photographers Cecil Beaton and Dorothy Wilding, well convey their own delighted pleasure at portraying a very handsome young woman who happens to be the new Queen: showing her regal status to the best of their ability was a task worth doing.

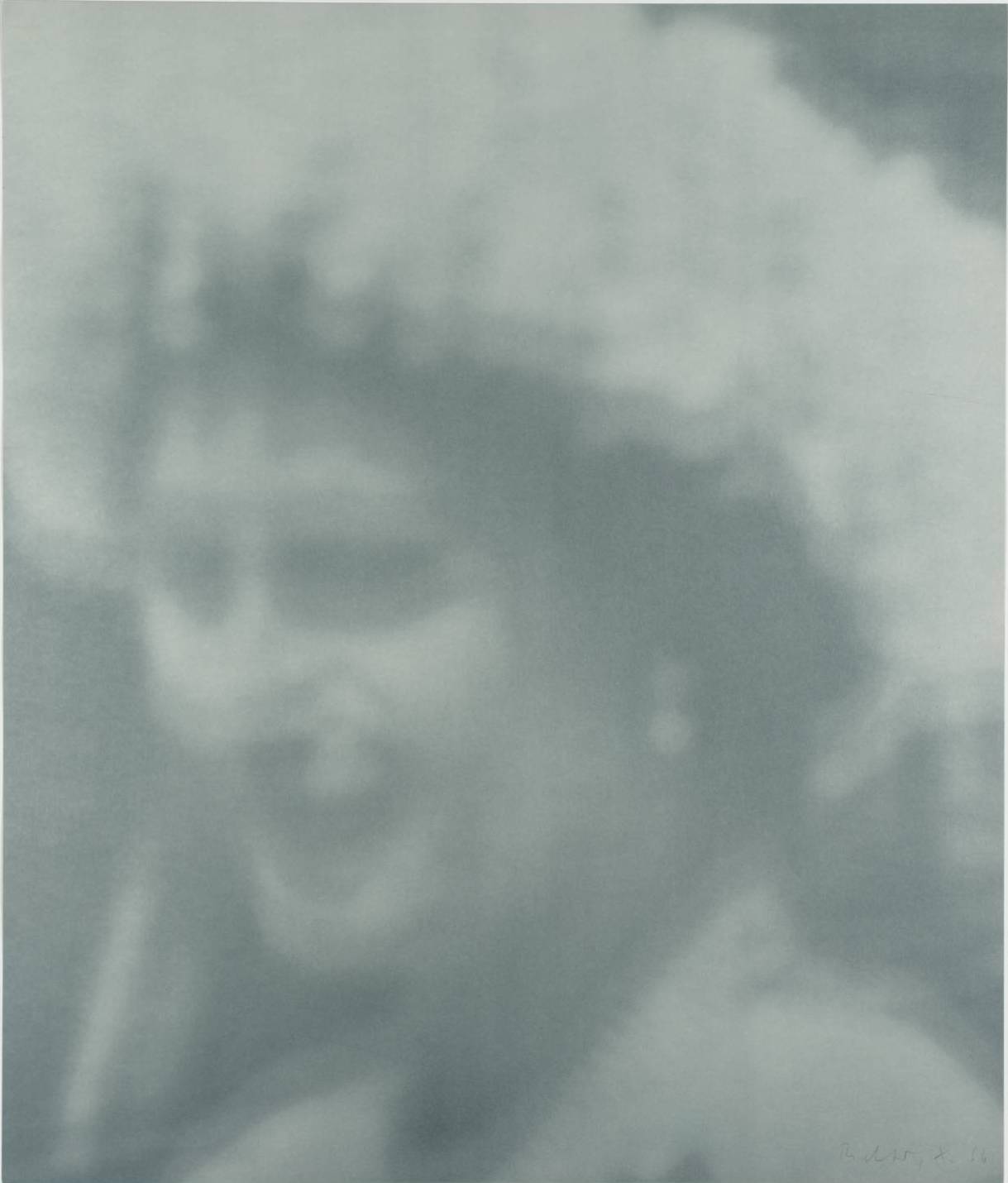

And occasionally a distinguished artist rises, unasked, to the challenge. Gerhard Richter’s 1966 lithograph (pictured right), based on a photograph which he has blurred and manipulated with varying tones of grey, conveys a sense of ambiguous and ambivalent unease, using his own well-known idiom to striking effect. Another provocatively thoughtful image is Hiroshi Sugimoto’s black-and-white photograph of the Queen literally as waxwork, the rather crass effigy at Madame Tussaud’s being his subject.

So there are some provoking and thoughtful works among the dross, but in the main the attempts to modernise are embarrassing, and the reportorial – Eve Arnold (pictured left: The Queen, 1968), Dylan Martinez, or those images credited to the Press Association – remain the most effective. Unlike the images of the monarchy from Van Dyck to Zoffany to even – yes - Winterhalter, there will be little of memorable artistic distinction in the Elizabethan legacy.

So there are some provoking and thoughtful works among the dross, but in the main the attempts to modernise are embarrassing, and the reportorial – Eve Arnold (pictured left: The Queen, 1968), Dylan Martinez, or those images credited to the Press Association – remain the most effective. Unlike the images of the monarchy from Van Dyck to Zoffany to even – yes - Winterhalter, there will be little of memorable artistic distinction in the Elizabethan legacy.

- The Queen: Art and Image at the National Portrait Gallery until 21 October

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment