Apocalypse Now | reviews, news & interviews

Apocalypse Now

Apocalypse Now

Coppola's phantasmagorical epic is re-released

More phantasmagorically beautiful than it ever had any right to be given its subject, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now begins as a nightmare, or a delirium, with thup-thup-thupping helicopters ghosting in and out of the frame in front of the jungle and wisps of yellow smoke rising in the foreground. Cymbals, noodling guitar and a tambourine played by The Doors on the track preface the voice of Jim Morrison, who exhaustedly croons the opening lines of “The End”.

The chopper blades in his mind merge with those of the ceiling fan in his Saigon hotel room. There’s a close-up of the fire, before the face of a great stone Buddha - ancient and impenetrable - appears on the right, a cautionary juxtaposition. The very last shot of the film sees Willard’s face blend with that of the Buddha, part of the jungle temple lair of Willard’s quarry, Colonel Walter E Kurtz (Marlon Brando). It’s as if Willard, having embraced “the horror”, like Kurtz, his secret sharer, has been absorbed finally by the jungle, "the heart of an immense darkness". Alienated from home at the start of the film, where the hell else was he going to go?

Coppola’s masterpiece is spectacular, trippy, mystical, portentous, dangerously pleasurable, and infinitely quotable

With that opening sequence, Coppola and the cinematographer Vittorio Storaro immediately established a language of dissolves to enhance the hallucinatory quality of the episodic horror show Willard will experience and narrate - the cleaner language of cutting would have been too stable for the chaos of Coppola’s Vietnam - as he proceeds up the fictional Nung River (the Mekong) in the late summer of 1969. His mission, clearly his last, is to “terminate… with extreme prejudice” Kurtz’s command.

Like his head-hunting antecedent in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the former Special Forces man has gone mad, fighting a private campaign of butchery against the Vietcong from his base in off-limits Cambodia. There is no greater manifestation of it than the shrine of skulls that Willard and his two surviving companions see from the boat. It is reminiscent of the heaped skulls in Vasily Vasilyovich Vereshchagin’s Apotheosis of War (1871), which the painter ironically dedicated “to all conquerors, past, present and to come”, but it also augurs the Cambodian genocide.

Watching and listening to Apocalypse Now recently, I was struck by the time-collapsing relevance of Morrison’s lines “lost in a Roman wilderness of pain/ And all the children are insane", which put me in mind of Clive James’s lyric for Pete Atkin, “There are helicopters on the walls of Troy”, in “The Last Hill That Shows You All the Valley”. Civilisations expand, become corrupt, practise atrocities and die, to be conflated with new ones in the poet’s eye. As for insane children, Colonel Bill Kilgore (pictured above: Robert Duvall, above with M-16, and Sam Bottoms as Lance), the leader of the Air Cavalry in Apocalypse Now, who has “The Ride of the Valkyries” foaming from his chopper’s loudspeakers as his squadron bombards a Vietcong village - “It scares the hell out of the slopes” - is scarcely less mad than Kurtz, despite being sanctioned by the brass to go “tear-assing around ‘Nam looking for the shit”, as Willard puts it (in the words of Michael Herr, who wrote the Chandleresque narration). And all of Kurtz's disciples, Montagnards and whites alike, have been brainwashed by his ferocious genius.

Watching and listening to Apocalypse Now recently, I was struck by the time-collapsing relevance of Morrison’s lines “lost in a Roman wilderness of pain/ And all the children are insane", which put me in mind of Clive James’s lyric for Pete Atkin, “There are helicopters on the walls of Troy”, in “The Last Hill That Shows You All the Valley”. Civilisations expand, become corrupt, practise atrocities and die, to be conflated with new ones in the poet’s eye. As for insane children, Colonel Bill Kilgore (pictured above: Robert Duvall, above with M-16, and Sam Bottoms as Lance), the leader of the Air Cavalry in Apocalypse Now, who has “The Ride of the Valkyries” foaming from his chopper’s loudspeakers as his squadron bombards a Vietcong village - “It scares the hell out of the slopes” - is scarcely less mad than Kurtz, despite being sanctioned by the brass to go “tear-assing around ‘Nam looking for the shit”, as Willard puts it (in the words of Michael Herr, who wrote the Chandleresque narration). And all of Kurtz's disciples, Montagnards and whites alike, have been brainwashed by his ferocious genius.

Willard, who is in the audience’s eyes and ears, has seen his own share of horrors in Vietnam, but as he journeys in the Navy PBR with its chief Phillips (Albert P Hall, pictured below), the machinist Chef (Frederic Forrest) and the young gunners Lance (Sam Bottoms) and Clean (Larry Fishburne), the notion of war fought on sex and drugs and rock'n'roll is impossible for him to grasp. Kilgore’s surfing obsession, the USO performance by the Playboy Bunnies, the battle at the psychedelically lit Do Long Bridge, and Lance’s dropping acid leave him incredulous. But he, too, partakes in the madness, ruthlessly firing the last lethal bullet in Clean and Lance’s hair-trigger attack on the sampan river traders. Redolent of the My Lai massacre, the scene as penned by Coppola and sound designer/editor/writer Walter Murch was initially disdained by the hawkish, pro-grunt Milius.

Thirty-two years after it shared the Palme d’Or with Volker Schlöndorff's The Tin Drum, Apocalypse Now remains the most outlandish of epic war films - certainly nothing like it has been attempted since, though Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982) were made with, and analysed in their narratives, the same sense of hubris. Combining elements of film noir, the western and the road movie, Coppola’s masterpiece is spectacular, trippy, mystical, portentous, dangerously pleasurable, and infinitely quotable (as Gary Oldman’s Nil by Mouth recognised) - “Charlie don’t surf!”, “I love the smell of napalm in the morning", “Never get out of the boat". It’s also dense in myth and metaphors and sardonic in its denunciations of war, imperialism and the Military-industrial complex: “The war was being run by a bunch of four-star clowns who were gonna end up giving the whole circus away," Willard reflects. In the era of Abu Ghraib and Halliburton contracts in Iraq, Coppola’s film seems as pertinent as ever.

Thirty-two years after it shared the Palme d’Or with Volker Schlöndorff's The Tin Drum, Apocalypse Now remains the most outlandish of epic war films - certainly nothing like it has been attempted since, though Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982) were made with, and analysed in their narratives, the same sense of hubris. Combining elements of film noir, the western and the road movie, Coppola’s masterpiece is spectacular, trippy, mystical, portentous, dangerously pleasurable, and infinitely quotable (as Gary Oldman’s Nil by Mouth recognised) - “Charlie don’t surf!”, “I love the smell of napalm in the morning", “Never get out of the boat". It’s also dense in myth and metaphors and sardonic in its denunciations of war, imperialism and the Military-industrial complex: “The war was being run by a bunch of four-star clowns who were gonna end up giving the whole circus away," Willard reflects. In the era of Abu Ghraib and Halliburton contracts in Iraq, Coppola’s film seems as pertinent as ever.

And Apocalypse is now again. Having been digitally restored by Zoetrope, it’s being re-released in cinemas in the UK today. On 13 June, it’s being issued in full high-definition widescreen on a three-disc Blu-ray edition. The discs also feature the extended version, Apocalypse Now Redux, the making-of documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Film-maker’s Apocalypse, and masses of bonus material, including a 49-minute interview with John Milius, who adapted the screenplay from Heart of Darkness, an hour-long conversation with Sheen and Coppola, 30 minutes of lost and additional scenes, and the six-minute "Kurtz Compound Destruction" sequence seen at the end of the 70mm release version.

The restored 153-minute theatrical version is the one to see. Redux, originally released in 2001, contains 50 minutes of footage omitted from the 1979 cut that collectively sap its energy. The added scenes humanised the conflict by softening Willard. For example, he is seen stealing Kilgore’s surfboard, incensing its deranged owner and building a bond between himself and the boys on the boat. In another added scene, the boys have further cause to like Willard when he buys them the sexual favours of the Bunnies with fuel for their downed helicopter at an abandoned medevac camp. But when Chef and Lance try to get it on with the girls, one twitters on about birds and the other about being abused in her job; the vague suggestion that the sexual exploitation of woman is akin to sending men to war is even more problematic now than it was before women in the US Army first entered combat.

Neither Phillips nor Willard touch the Bunnies, but we learn of Phillips’s fatherly feelings toward Clean when he buries the dead youth at the beginning of the restored French plantation sequence. Over dinner, the French patriarch (Christian Marquand) gives Willard an arrogant imperialistic history lesson, concluding, “You Americans fight for the biggest nothing in history." His bickering relatives storm out and Willard spends the night with a young widow, Roxanne (Aurore Clément) in an opium haze. The tender scene reveals Willard’s vulnerability, but a reference to the Henri Martin Affair of 1950-53 indicates these French are literally ghosts from the First Indochina War.

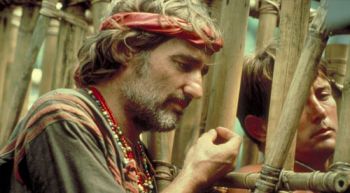

Coppola and Murch, who edited Redux, restored one scene involving Kurtz. He reads to the incarcerated Willard a Time magazine report of an intelligence officer’s commendation of America’s progress in the war to President Nixon. Kurtz sneers at this obvious lie - the lies the American leaders tell the people being a major theme - and we would see him as a more humane man at this point if he hadn’t decapitated Chef the night before. Some might consider it a boon that there’s no extra footage of the drug-addled, TS Eliot-quoting photojournalist, a weird composite of Charles Manson and the Vietnam war photographer Tim Page played by the drug-addled Dennis Hopper (pictured above, with Martin Sheen). But in his Apocalypse Now book Karl French has persuasively argued that Hopper’s character, inspired by Conrad’s Russian trader and an apologist for Kurtz, valuably reinforces the connections between the novella and the film.

Coppola and Murch, who edited Redux, restored one scene involving Kurtz. He reads to the incarcerated Willard a Time magazine report of an intelligence officer’s commendation of America’s progress in the war to President Nixon. Kurtz sneers at this obvious lie - the lies the American leaders tell the people being a major theme - and we would see him as a more humane man at this point if he hadn’t decapitated Chef the night before. Some might consider it a boon that there’s no extra footage of the drug-addled, TS Eliot-quoting photojournalist, a weird composite of Charles Manson and the Vietnam war photographer Tim Page played by the drug-addled Dennis Hopper (pictured above, with Martin Sheen). But in his Apocalypse Now book Karl French has persuasively argued that Hopper’s character, inspired by Conrad’s Russian trader and an apologist for Kurtz, valuably reinforces the connections between the novella and the film.

One positive effect of the restored scenes in Redux is to balance the film’s combat sequences and its complex mythic subtext. After the press screening I attended in 2001, I overheard a woman telling her friends she had expected Willard, having ritually executed Kurtz, to succeed him as the ruler of his Montagnard cult - one of the three endings Coppola, stuck in the Philippines without a conclusion, apparently contemplated. Instead, he opted for that merging of Willard with the Buddha as Kurtz’s dying whisper, “The horror! The horror!”, is repeated. The quote comes from Heart of Darkness; Eliot, whose poems are in Kurtz’s "library", had once intended these words as an epigraph to The Waste Land, which is visually echoed in Willard’s journey, with the terrain (a burning chopper and its dead crew hanging in trees, a downed B-52 sticking up from the river, corpses and heads proliferating) beginning to resemble a modern equivalent of Pieter Breughel the Elder’s The Triumph of Death (c 1562). One could argue that without the air strike, the film ends “not with a bang but a whimper” - the last lines from Eliot’s The Hollow Men, and one of the last spoken by the photojournalist before he quits the stage like Lear’s Fool - but it's a near perfect decrescendo.

Whether she knew it or not, the woman at the screening was invoking the Fisher King of Grail legend fame, inscribed by Eliot in The Waste Land as a metaphor for moral and spiritual decline in the 20th century. The Fisher King is the pan-cultural mythic figure that Sir James Frazer in The Golden Bough and Jessie L Weston in From Ritual to Romance, books glimpsed in Kurtz’s room in the film (the latter a key influence on The Waste Land), traced back to pre-Christian fertility cults. Because the Fisher King is sick or maimed in the legs or groin, in other words impotent, his people have become infertile and his country a wasteland. A knight can replenish the land by healing and succeeding him, or, as in the case of Willard, killing him. (Kurtz also owns a Bible; Peter Cowie, author of The Apocalypse Now Book, claims that The Sleepwalkers, Arthur Koestler’s history of cosmology and the phenomenon of scientific discovery, can also be seen among Kurtz's possessions.)

The Conrad-Eliot-Frazer-Weston matrix is the key to understanding what French recognises as Apocalypse Now’s role in “the spiritual continuum that links modern myths to those of Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism and pagan rituals". The film’s skein of references draws the Kilgore brand of slaughter and the mutilations carried out by Kurtz’s cadre into a timeless cycle of decay and rebirth. Suggested to Coppola by Dennis Jakob, an old UCLA buddy of the director (and Jim Morrison), the Fisher King myth is the film's secret history, which, happily contains “lance” imagery, and the source of the ending that took so long for Coppola to settle on. “I was dealing with moral issues,” he said in 1987, “and I didn’t want to have just the typical John Milius ending, when the NVA attack and there’s a gigantic battle scene, and Kurtz and Willard are fighting side by side, and Kurtz (Marlon Brando, pictured above) gets killed, etc, etc.”

The Conrad-Eliot-Frazer-Weston matrix is the key to understanding what French recognises as Apocalypse Now’s role in “the spiritual continuum that links modern myths to those of Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism and pagan rituals". The film’s skein of references draws the Kilgore brand of slaughter and the mutilations carried out by Kurtz’s cadre into a timeless cycle of decay and rebirth. Suggested to Coppola by Dennis Jakob, an old UCLA buddy of the director (and Jim Morrison), the Fisher King myth is the film's secret history, which, happily contains “lance” imagery, and the source of the ending that took so long for Coppola to settle on. “I was dealing with moral issues,” he said in 1987, “and I didn’t want to have just the typical John Milius ending, when the NVA attack and there’s a gigantic battle scene, and Kurtz and Willard are fighting side by side, and Kurtz (Marlon Brando, pictured above) gets killed, etc, etc.”

If this was also the source of Apocalypse Now being labelled pretentious, it seems to me a wholly successful conclusion to a film of Heart of Darkness, and as good a reason as “The Ride of the Valkyries” or the PBR’s momentous approach to the temple and the Montagnard greeting party to keep one returning to Coppola's classic again and again.

Elements of this article appeared in Graham Fuller's Interview magazine column in August 2001

Watch the trailer for Apocalypse Now

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

Freakier Friday review - body-swapping gone ballistic

Lindsay Lohan and Jamie Lee Curtis's comedy sequel jumbles up more than their daughter-mother duo

Freakier Friday review - body-swapping gone ballistic

Lindsay Lohan and Jamie Lee Curtis's comedy sequel jumbles up more than their daughter-mother duo

Add comment