Punk Britannia, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Punk Britannia, BBC Four

Punk Britannia, BBC Four

Blatant revisionism makes this documentary a missed opportunity on several fronts

“We didn’t have a real agenda. We just wanted to play some tunes and have a good time.” Thus spoke the immaculately suited but still mischievous-looking Mick Jones. And thank goodness he said it because, from the off - even before the off - I didn’t think anyone would. The interviewer (his ideological preconceptions crumbling) protested, so unfortunately Jones had to qualify his unguarded statement by saying he couldn’t of course speak for the other members of The Clash.

Yes, it would seem from this first of three programmes that Punk Britannia is going once again (for many music writers and TV programmes have been here before) to impose retrospectively great cultural significance on what was in reality just some vaguely bored, vaguely angry and vaguely musical youths who learnt some barre chords and revelled in kicking up a racket. Anyone scrutinising the footage can see it in Johnny Rotten’s eyes and Jones’s lopsided grin: punk was about cheek rather than anarchy; it was about boredom rather than revolutionary zeal. As one-time Doctor of Madness Richard Strange put it with reference to the Sex Pistols: “They were naughty but not excessively so. They looked like kids bunking off school.”

This focus on cultural context and subtext was the expected flaw. Less expected was how little emphasis was placed upon both American rock and glam rock as defining influences. Instead, the more tenuous (at least in a musical sense, which is surely the most important sense) connection to pub rock took up most of this first hour. Maybe this was because there was no shortage of old pub rockers to wax nostalgic about sweaty nights down the Hope & Anchor while simultaneously shrinking away in horror at the very thought of the men in frocks and make-up who actually impacted more on the likes of Rotten, Jones and the still cinematically striking Siouxsie (pictured above right) - who hopefully we'll see more of in the other episodes).

This focus on cultural context and subtext was the expected flaw. Less expected was how little emphasis was placed upon both American rock and glam rock as defining influences. Instead, the more tenuous (at least in a musical sense, which is surely the most important sense) connection to pub rock took up most of this first hour. Maybe this was because there was no shortage of old pub rockers to wax nostalgic about sweaty nights down the Hope & Anchor while simultaneously shrinking away in horror at the very thought of the men in frocks and make-up who actually impacted more on the likes of Rotten, Jones and the still cinematically striking Siouxsie (pictured above right) - who hopefully we'll see more of in the other episodes).

The impact of pub rock was strategic rather than musical, as the documentary implicitly illustrated. The pub rock managers persuaded countless London pub landlords to rent out their backrooms as music venues, so that the ever-evolving Londoner got used to going out to see bands live that otherwise they wouldn’t have known existed. The only bands that transcended the pedestrian predictability of many of these rock'n'roll nostalgists were Kilburn & the Highroads, Dr Feelgood and fellow Canvey Island rockers Eddie & the Hotrods. The rest were - if not despised by the punks - certainly seen as irrelevant, which is arguably just as damning.

So, what of glam rock then? Well, we got a glimpse of that recently discovered footage of Bowie doing “The Jean Genie” on Top of the Pops (see video below), and Adam Ant saying, “There would have been no punk rock without glam”, but that was about it. Yet the punk generation were in their early to late teens when Bowie and Bolan first thrust their sexual ambiguity into the faces of the British public. Surely this made it almost inevitable that those who delighted in the affront would in turn want to shock or disconcert once they’d got hold of their first guitar. But long hair had been done, 20-minute guitar solos had been done, and sex had been done. So what was left? Pantomime anger and slapstick nihilism.

Returning to cultural revisionism for a moment, Strange’s touchingly romantic notion of a baton of protest being handed on, because the first Sex Pistols gig occurred just a couple of months after America’s surrender in Vietnam, verged on parody: if history isn’t made then make up history. But who could blame him for joining in the game? Documentaries like this are a licence to self-aggrandise - even for those who were on the periphery of what's being retrospectively spot-lit. And of course you could almost hear the director lapping it up.

Returning to cultural revisionism for a moment, Strange’s touchingly romantic notion of a baton of protest being handed on, because the first Sex Pistols gig occurred just a couple of months after America’s surrender in Vietnam, verged on parody: if history isn’t made then make up history. But who could blame him for joining in the game? Documentaries like this are a licence to self-aggrandise - even for those who were on the periphery of what's being retrospectively spot-lit. And of course you could almost hear the director lapping it up.

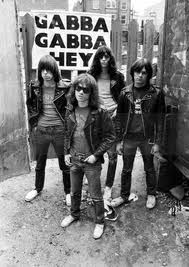

Talking of America, here was the other curious hole in this programme. American rock was a huge influence on this first generation of UK punks, yet there was no mention of Iggy Pop, The Flaming Groovies, Alice Cooper or even The Ramones (pictured). The first UK punk rock single, The Damned’s “New Rose”, was absolutely steeped in The Ramones - I’d even go as far as to suggest this record wouldn’t have existed without The Ramones' first album as a template. But then up pops the producer of “New Rose”, Nick Lowe (one of the aforementioned pub rockers keeping up with the times), to call the record “startlingly original”. What? Did he really just say that? Surely such nonsense could have been balanced with a clip of The Ramones going through their almost identical paces on just about every one of their songs. Ramones was released in April of 1976, “New Rose” came out in September. And The Ramones had been knocking out fuzzy, wall-of-noise, two-minute dumb-ass speed rock since 1974.

OK, so this was Punk Britannia not Punk: A Proper Objective History. But would a smidgen of international context really have damaged our oh-so-delicate British pride, even in this bunting-festooned Diamond Olympic Jubilee of a year? On the plus side, a cast list which also included John Lydon, Billy Idol, Paul Weller, the great Wilko Johnson and a disconcertingly Thatcher-esque Caroline Coon at least made the hour pass quickly. Perhaps parts two and three will edge a little nearer to some kind of truth.

David Bowie performs "The Jean Genie" on Top of the Pops

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

I think the same set of

Revisionism? Everyone's got