theartsdesk in Göttingen: Handel With an Umlaut | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Göttingen: Handel With an Umlaut

theartsdesk in Göttingen: Handel With an Umlaut

Nicholas McGegan's bouncing era at the international festival comes to a close

Georg Friedrich Händel of Halle probably never came here. Other great men certainly did: long after the official foundation of Göttingen's Georg August University in 1734 - the year in which the composer wrote a masterpiece, Ariodante, in another spa town, Tunbridge Wells - would-be or successful students included Goethe, Heine, the Brothers Grimm, Schopenhauer and Bismarck. It's hardly a Baroque town, either, though its beauties are manifold.

Nic, as the Göttingers all seem to know him, hands over the reins at the end of this year's International Handel Festival to Laurence Cummings, as John Eliot Gardiner handed them over to him back in 1991. He's left his indelible mark with a reinvigorated string of Handel operas many of us first heard about with the CD release of the 1995 Ariodante, starring the late, lamented but ever-glorious Lorraine Hunt Liberson (or not-so-plain Lorraine Hunt as she was then known). Göttingen may not have heard a voice of such searing individuality since, but McGegan has built an ensemble of world-class regulars around him; one of them, top counter-tenor Robin Blaze, told me that he'd never have dreamt of leaving a young family behind in England for five weeks in Germany were it not for the electrifying music-making McGegan always seems to draw.

Blaze was one of the two top stylists in this year's Handel opera, an early Italian extravaganza for London. Teseo, linked to the 2011 festival's French-connection theme by virtue of its libretto being drawn from a five-act tragédie lyrique for Versailles with music by Lully, might well be called Medea. Its chief gambit is to show the sorceress in her full range of love and wrath, with attendant spectacles. The resident diva is Dominique Labelle (pictured above right), possessed of the cheekbones, the temperament and the deportment but not quite the technique to support the fireworks; she has two modes - loud and luscious, or near-inaudible. Much less could I quite believe what I was hearing from Susanne Rydén as the hero, all over the shop stylistically (update: I've only just learned that she was suffering from quite an illness all through the rehearsal period, and had undergone a course of antibiotics leading up to the performance. The festival should certainly have made an announcement).

Blaze was one of the two top stylists in this year's Handel opera, an early Italian extravaganza for London. Teseo, linked to the 2011 festival's French-connection theme by virtue of its libretto being drawn from a five-act tragédie lyrique for Versailles with music by Lully, might well be called Medea. Its chief gambit is to show the sorceress in her full range of love and wrath, with attendant spectacles. The resident diva is Dominique Labelle (pictured above right), possessed of the cheekbones, the temperament and the deportment but not quite the technique to support the fireworks; she has two modes - loud and luscious, or near-inaudible. Much less could I quite believe what I was hearing from Susanne Rydén as the hero, all over the shop stylistically (update: I've only just learned that she was suffering from quite an illness all through the rehearsal period, and had undergone a course of antibiotics leading up to the performance. The festival should certainly have made an announcement).

The more credit to young English soprano Amy Freston (pictured left) as Theseus's true love Agilea, for staying cool in their lovers-reconciled duet. She had a hell of an early challenge keeping tabs on the most brilliant of the many oboe solos in the youthful Handel's experimental ferment, but her light lyric soprano eased beautifully into the pathos of the fourth act, and an aria which you can't help but think Mozart might have had in mind when he composed Pamina's "Ach, ich fühls" in Die Zauberflöte. That and Blaze's Act III showpiece were the flawless vocal highlights of the evening.

The more credit to young English soprano Amy Freston (pictured left) as Theseus's true love Agilea, for staying cool in their lovers-reconciled duet. She had a hell of an early challenge keeping tabs on the most brilliant of the many oboe solos in the youthful Handel's experimental ferment, but her light lyric soprano eased beautifully into the pathos of the fourth act, and an aria which you can't help but think Mozart might have had in mind when he composed Pamina's "Ach, ich fühls" in Die Zauberflöte. That and Blaze's Act III showpiece were the flawless vocal highlights of the evening.

Ultimately, though, it was McGegan's Göttingen Festival Orchestra which surely brought the initially reserved, ultimately genial audience to its feet. The sound in the small - 500-seater - early-20th-century auditorium of the Deutsches Theater has to be heard to be believed. It helps that, with the resident opera company long gone - the theatre now plays host to a, by all accounts, fine dramatic repertory company - the pit has been closed off and the players are out front on the parterre, with the wind facing the stage like the front row of stalls. But even so I was quite taken aback by the rocking, thundering sound of Handel's ever-inventive bass lines, the two Italian double bassists just below stage right and left: a cornucopia of invention which could only remind one of the pop-hits essence which surely makes Handel opera as widely popular as it is today. But it has to be served up fresh and vital, and it was.

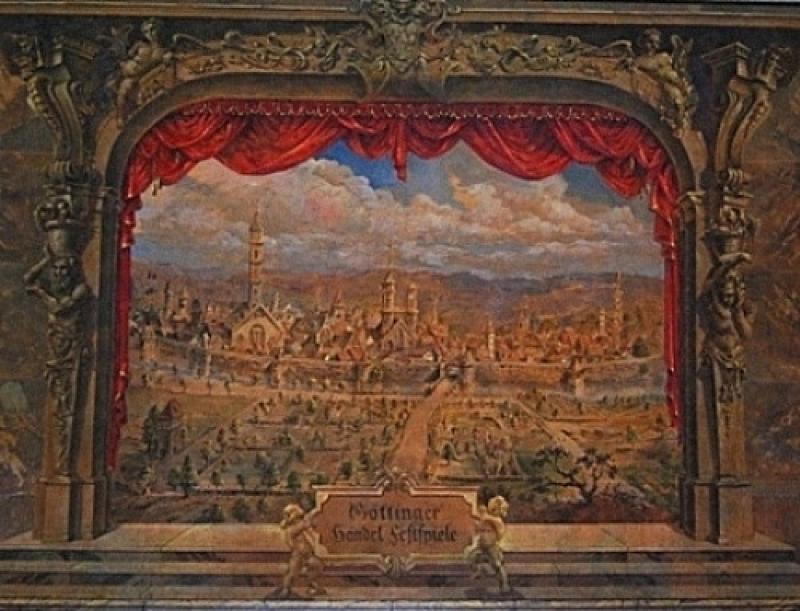

At first it looked as if the authentic visuals were going to match the aural spectacular. Long gone are the Expressionist whimsies of Oskar Hagan's wilfully inauthentic 1920s Handel in Göttingen (the 1927 production of Radamisto pictured right). McGegan has worked most often since 1991 with Baroque set designer Scott Blake and director/choreographer Bonnie Kruger. Frankly I could do without the mimsy efforts of the New York Baroque Dance Company - more prancing than dancing, it seems to an outsider, and too much amateurish standing around looking astonished at the goings-on in between; and in any case Teseo, unlike say Alcina, is short on spectacle ballets, so some numbers had to be drafted in to the illusory garden scene of Act IV.

At first it looked as if the authentic visuals were going to match the aural spectacular. Long gone are the Expressionist whimsies of Oskar Hagan's wilfully inauthentic 1920s Handel in Göttingen (the 1927 production of Radamisto pictured right). McGegan has worked most often since 1991 with Baroque set designer Scott Blake and director/choreographer Bonnie Kruger. Frankly I could do without the mimsy efforts of the New York Baroque Dance Company - more prancing than dancing, it seems to an outsider, and too much amateurish standing around looking astonished at the goings-on in between; and in any case Teseo, unlike say Alcina, is short on spectacle ballets, so some numbers had to be drafted in to the illusory garden scene of Act IV.

But this was as nothing compared to the promise of giving the work a "contemporary twist" - to whit, a screen far too high above the stage for the front rows of the stalls to crane upwards to watch. It seemed to be loosely narrating some sort of backstage shenanigans interlaced with Labelle commenting on Facebook, but clearly it was information overload, and could only distract from the stylised movements on stage. There was some valiant video projection work for Medea's dire hellish transformation scenes, but as so often they sat uneasily with the pretty basics of the Baroque stage picture.

I'd hate to give the impression that, in spite of some of the miscasting and the misdirecting, I left the theatre on the first night anything but elated; McGegan's charismatic direction was far too good for disappointment. And later that evening, flanked by personifications of civic artistry in the expert 1880s refrescoing of the much-modified medieval town hall, he received a major award to follow an honorary professorship in Göttingen University's faculty of humanities and (last year) an OBE. This time it's the Cross of the Lower Saxony Order of Merit (Verdienstkreuz am Bande), and the German State Secretary in charge of cultural affairs, Dr Joseph Lange, was there to award it, telling McGegan and us that "by integrating historical elements into performance and cultivating an exceptional joy in music-making, you have endowed the International Handel Festival with a unique artistic character, while delighting its audiences". And no one would disagree with that, least of all the cohort of singers who came on one by one to line the stairs of the Great Hall, sopranos and mezzos arrayed in raiment of catwalk elegance.

I'd hate to give the impression that, in spite of some of the miscasting and the misdirecting, I left the theatre on the first night anything but elated; McGegan's charismatic direction was far too good for disappointment. And later that evening, flanked by personifications of civic artistry in the expert 1880s refrescoing of the much-modified medieval town hall, he received a major award to follow an honorary professorship in Göttingen University's faculty of humanities and (last year) an OBE. This time it's the Cross of the Lower Saxony Order of Merit (Verdienstkreuz am Bande), and the German State Secretary in charge of cultural affairs, Dr Joseph Lange, was there to award it, telling McGegan and us that "by integrating historical elements into performance and cultivating an exceptional joy in music-making, you have endowed the International Handel Festival with a unique artistic character, while delighting its audiences". And no one would disagree with that, least of all the cohort of singers who came on one by one to line the stairs of the Great Hall, sopranos and mezzos arrayed in raiment of catwalk elegance.

There was no holiday for the performers after that late-night feast; the next Teseo was at 3pm on a sweltering Saturday. I spent the day exploring the delights of Göttingen, and I only touched the tip of the iceberg - wrong metaphor for a near-midsummer, Meistersingerish experience - by walking the walls, thrilling to the trilling of the frogs in the lily pond of the university's fabulous botanic garden, examining the gaudily painted facades of the town's finest Renaissance facades and wandering among the outrageously painted barley-sugar columns of the Lutheran parish church of St James. There was just time for a bike ride up to the ancient forest of the Hainberg on the slopes above the town before the evening's two concerts. The first took place in the much-restored Romanesque Church of St John behind the town hall, with its lopsided towers (a belfry and a watchtower, pictured above from Paulinerstrasse). This was one of the two per cent of town-centre buildings to be bombed in the Second World War; Göttingen was largely spared the ravages of all its neighbours. Why? Rumour has it that a universities-conscious deal was done between enemies: you spare Göttingen and Heidelberg, we'll avoid Oxford and Cambridge.

There was no holiday for the performers after that late-night feast; the next Teseo was at 3pm on a sweltering Saturday. I spent the day exploring the delights of Göttingen, and I only touched the tip of the iceberg - wrong metaphor for a near-midsummer, Meistersingerish experience - by walking the walls, thrilling to the trilling of the frogs in the lily pond of the university's fabulous botanic garden, examining the gaudily painted facades of the town's finest Renaissance facades and wandering among the outrageously painted barley-sugar columns of the Lutheran parish church of St James. There was just time for a bike ride up to the ancient forest of the Hainberg on the slopes above the town before the evening's two concerts. The first took place in the much-restored Romanesque Church of St John behind the town hall, with its lopsided towers (a belfry and a watchtower, pictured above from Paulinerstrasse). This was one of the two per cent of town-centre buildings to be bombed in the Second World War; Göttingen was largely spared the ravages of all its neighbours. Why? Rumour has it that a universities-conscious deal was done between enemies: you spare Göttingen and Heidelberg, we'll avoid Oxford and Cambridge.

Anyway it was there that five young soloists, a vigorous youth choir, the Landesjugendchor Niedersachsen, and a well-established early-music band, Musica Alta Ripa under Jörg Straube (all pictured left), flanked the stately ceremonials of Lalande's Te Deum with the rather more individual glories of Handel's four 1727 anthems for the coronation of George II. It was a powerful experience to hear the lofty Catholic ritual of Lalande's lilting splendour for Louis XIV against the quirky pleasures of Handel's more intimate Lutheran-within-CofE sweetness; though it could be strong, if unconscious, affiliations with the latter that made me reel at the personable trills of "The King shall rejoice". Or maybe just the fact that the work is an official masterpiece. At any rate, even if adolescent tenors and basses couldn't quite bring the ideal ballast, the choristers brought an ideal exuberance to another event that sent everyone out bursting with joy.

Anyway it was there that five young soloists, a vigorous youth choir, the Landesjugendchor Niedersachsen, and a well-established early-music band, Musica Alta Ripa under Jörg Straube (all pictured left), flanked the stately ceremonials of Lalande's Te Deum with the rather more individual glories of Handel's four 1727 anthems for the coronation of George II. It was a powerful experience to hear the lofty Catholic ritual of Lalande's lilting splendour for Louis XIV against the quirky pleasures of Handel's more intimate Lutheran-within-CofE sweetness; though it could be strong, if unconscious, affiliations with the latter that made me reel at the personable trills of "The King shall rejoice". Or maybe just the fact that the work is an official masterpiece. At any rate, even if adolescent tenors and basses couldn't quite bring the ideal ballast, the choristers brought an ideal exuberance to another event that sent everyone out bursting with joy.

After a balmy-evening break for seasonal white asparagus and a glass of Handelwein in the main square, it was on to a late-night special in the slightly more intimate, pleasingly austere surroundings of 14th-century St Mary's. All-French music this time in the stylish hands of American-based Voices of Music, from recorder-led suites dominated by the dazzling Dan Laurin - when was such an instrument ever more virtuoso fun? - to the intimate novelty of Couperin's classic enigma Les barricades mystérieuses in the subtle hands of harpsichordist Hanneke von Proosdij.

So that was my little slice of Baroque heaven in medieval-and-Enlightenment Göttingen. But there was one final, serendipitous ceremony encountered just before I caught my early-Sunday-morning train back to Frankfurt. Walking through the town centre streets at 7am, I was hailed by a quintet of students, two of them performing a very traditional ritual on the Art Nouveau statue of the goosegirl in the town square. Recipients of the PhD kiss the maiden, 110 years old last week, on the cheek and present her with flowers and candles, which is just what the young medics flanking the girls in the picture above had done. In Göttingen local charm doesn't have to be laid on for the tourist; it just happens.

So that was my little slice of Baroque heaven in medieval-and-Enlightenment Göttingen. But there was one final, serendipitous ceremony encountered just before I caught my early-Sunday-morning train back to Frankfurt. Walking through the town centre streets at 7am, I was hailed by a quintet of students, two of them performing a very traditional ritual on the Art Nouveau statue of the goosegirl in the town square. Recipients of the PhD kiss the maiden, 110 years old last week, on the cheek and present her with flowers and candles, which is just what the young medics flanking the girls in the picture above had done. In Göttingen local charm doesn't have to be laid on for the tourist; it just happens.

And forget the curiously xenophobic English cliché that German cities and towns are over-orderly and boring; Göttingen has as genial a design for living as any I've encountered in central Europe.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Add comment