Barenboim, Staatskapelle Berlin, Boulez, Royal Festival Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Barenboim, Staatskapelle Berlin, Boulez, Royal Festival Hall

Barenboim, Staatskapelle Berlin, Boulez, Royal Festival Hall

Mastery and quirkiness but no transcendentalism in Liszt and Wagner

What next - Boulez and Daniel Barenboim in Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov? The two numbered Liszt concertos are probably as far as they're going to go in lacier romantic repertoire, and last night it didn't feel far enough to justify the predictable standing ovation.

Curiously, of the two it was Barenboim who fell shorter of every facet required by Liszt's artificially if intriguingly constructed experiments in concerto form. His playing felt a bit warhorsy in double-octave cannonades, sustaining pedal covering the hit-and-miss heavier attacks where you felt a younger pianist might have coruscated more clearly and with greater exuberance. The final victory charges of both concertos, too, fell a bit short of the bravura which justifies the means to an end, though this may have been the aim of the partnership - not one that worked for me, given Liszt's limited if always tuneful rhetoric. But in between there was much novelty: the left-hand roar as the Second stokes up its resources, the pearly dialogues with sophisticated orchestral soloists at the heart of the later "symphony-concerto" and the treatment of the First's inner movements as contrasting transcendental studies.

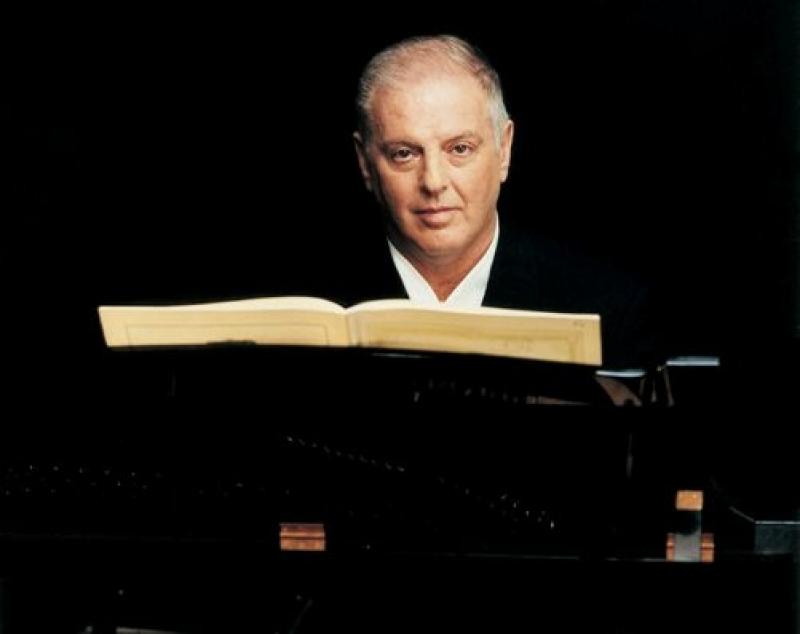

Pierre Boulez (pictured below by A Warme-Janville) encouraged real teamwork from the Berliners, with the best effect first - the way the woodwind launch immediately into the chord-driven melody which dominates the Second Concerto - and translucent string lines, evading the charge of thickness that's more a provenance of Liszt's symphonic poems (which I somehow doubt the master of exquisite sonorities will be tackling any time soon, though he may yet surprise us). But that sliver of ice in the soul which came in useful for shaping Liszt's romantic torrents chilled the baby blood of Wagner's Siegfried Idyll.

It may have been the halfway-house violin sections (two desks apiece, reduced from the still slender-seeming five in the Liszt) which made this feel like a chilly compromise between the chamber ensemble Richard crammed into his lakeside villa for his Cosima on her birthday - a format poetically realised by Pappano and Royal Opera soloists in the Cadogan Hall - and the Karajanesque scale which can also work well, given sufficient tenderness from the conductor.

Why was it, then, that despite his careful nurturing of every dynamic, Boulez's interpretation felt more like an amniotic homage to the unborn child rather than Wagner's intended welcoming to human activity of his infant son? Even the middle sequence failed to wake up to jolly, articulate life, and though the coda was finely shaded, that elusive degree of humanity kept slipping away between the phrases.

Why was it, then, that despite his careful nurturing of every dynamic, Boulez's interpretation felt more like an amniotic homage to the unborn child rather than Wagner's intended welcoming to human activity of his infant son? Even the middle sequence failed to wake up to jolly, articulate life, and though the coda was finely shaded, that elusive degree of humanity kept slipping away between the phrases.

On the other hand Boulez can't be praised too highly for daring to programme Wagner's early Faust Overture. To be sure, it's no quality match for the comparable specimens by Wagner's great predecessor Weber, and other more spooky homages to the supernatural popped up in the 1840s, not least Verdi's Macbeth and Wagner's own roughly contemporary Flying Dutchman, which briefly seethes in this sketch for the Faust Symphony that Liszt was later to write, along with premonitory Tristanesque love-heavings and a hint of Tannhäuser's holy Elizabeth in what's presumably the Gretchen theme. Again Boulez weighed the light and shade in the work with unerring and far from unshapely judgment.

But it wasn't until Barenboim's encore that the gift to be simple which had been less than well served in the Siegfried Idyll really worked its magic: the chiaroscuro he brought to the Valse oubliée No 1 marked the possible start of a whole new adventure, a probing of Liszt's more mysterious genius, for which we will simply have to wait on a solo recital.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Add comment