Giving his press conference speech at the opening of Kiev’s first international art biennale, David Elliott, the seasoned British curator charged with its organisation, looked exhausted, though far from triumphant and more than a little irate. “It’s not the way I usually handle things,” he said. He had opened his speech with an apology – some of the exhibits were still not ready. Meanwhile, the attendant press, who had come from as far as Tokyo, New York and London, were perhaps also a little disgruntled. The official opening had been scheduled for 11am that morning but it was now pushing 5pm.

The 36-hour power cut that had disrupted installation was offered by way of mitigation. With no back-up generators made available, Elliott (below right) and his team had worked in the dark, in the cavernous depths of a vast former munitions warehouse situated on a hill overlooking Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, a cave monastery founded in 1051 and one of the biggest Orthodox shrines in the Ukraine. And more than once Elliott hinted at the organisational chaos he had encountered in the preceding months.

There was a beautiful coherence to this vast and ambitious display

With the large number of video works included, one can imagine the sense of “never again” that accompanied Elliott’s exasperation. A stalwart of the international art scene – he was director of the 2010 Sydney Biennale and former director of museums and galleries in Stockholm, Tokyo and Istanbul – this was Elliott’s first curatorial excursion in the former Soviet state. The multi-million pound enterprise was being part-funded by the government in time for the UEFA Euro cup games the following month, of which they were co-hosts. The biennale was meant to be a major cultural showcase for a nation where a third of the population struggles beneath the poverty line and political corruption appears endemic. Former president Viktor Yushchenko was the target of an assassination attempt and the victim of poisoning in the run-up to the 2005 presidential election, while last year former prime minister and opposition politician Yulia Tymoshenko was imprisoned for seven years for negotiating with Russia over the price of natural gas, after a trial that was condemned in the West as politically motivated.

And while political freedoms are still being fought for, artistic ones are far from having been won. On the day of the biennale opening, the National Art Museum of Ukraine, which had an unrelated exhibition of contemporary artists who’d been invited to respond to Ukrainian baroque art of the past, had taken down gold-covered rubber ventilation pipes that were coiled around its neo-classical facade. It was felt that the work was in bad taste, that it lacked respect for the country’s heritage. Though it was later reinstalled, the artist, Olga Milentiy, talked about the lack of artistic freedom in her country.

And while political freedoms are still being fought for, artistic ones are far from having been won. On the day of the biennale opening, the National Art Museum of Ukraine, which had an unrelated exhibition of contemporary artists who’d been invited to respond to Ukrainian baroque art of the past, had taken down gold-covered rubber ventilation pipes that were coiled around its neo-classical facade. It was felt that the work was in bad taste, that it lacked respect for the country’s heritage. Though it was later reinstalled, the artist, Olga Milentiy, talked about the lack of artistic freedom in her country.

None of this appeared to bode well, but, as it turned out, Kiev’s first biennale, in the magnificently atmospheric Mystetskyi Arsenal, was anything but a wash-out. In fact, quite the opposite. It was exhilarating. And this despite encountering, on press day, far too many empty rooms where the art works were indicated only by label. It was disappointing not to see Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s film The Annunciation, or Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s substantial work Monument to a Lost Civilisation. No sign, either, of Bill Viola’s video, The Raft. And there were rumours that it wasn’t just a case of works not being ready, but of artists simply pulling out, fed up with the way things were being run, though, in fact, all the works were eventually installed.

But with over 100 artists and 220 works, from international artists as well as a strong contingent of lesser-known Ukrainian ones, there was still hours' worth of art to see. And there was a beautiful coherence to this vast and ambitious display. Under Elliott’s title The Best of Times, The Worst of Times. Rebirth and Apocalypse in Contemporary Art, the exhibition gave us a series of relationships that reinforced an overall theme, one that seemed, at times, achingly poignant. Here we were raking over a past of lost dreams and dystopian nightmares. And even when the works had little to do with dictatorships and tyrannies, juxtapositions enabled them to take on whole new resonances. There was an eloquence to this display that belied an apparently unwieldy bagginess.

One of the most low-key but evocative works was Erbossyn Meldibekov’s photographic series Family Album. Old family photos taken during the Soviet era in Kazakhstan showed the artist’s relatives gathered in front of statues of Lenin. Next to these were post-Soviet photos taken by the artist himself: the same family, the same spot, some 20 years later. Lenin had been replaced by monuments to the country’s more distant past in acts of cultural erasure that were inevitably reminiscent of Soviet times.

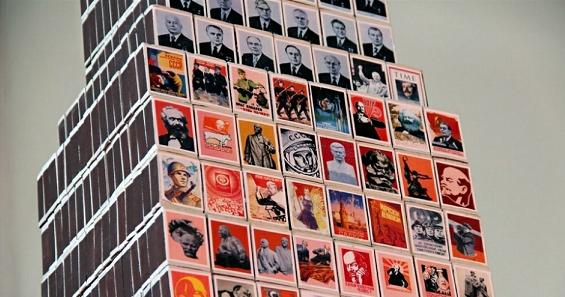

Dictators were uppermost in mind in Vyacheslav Akhunov’s red-carpet display Alley of Superstars. Here the painted faces of world leaders, past and present, were imprinted on a red carpet, with each face encircled inside a big, spangly star, like a Hollywood hall of fame: Castro, Franco, Chavez, Stalin, Ceausescu, Pol Pot. Marx was there, too and so was Tony Blair, at which point you wondered whether this reduced the work to a certain platitudinous glibness. The work was made between 2008 and 2012, and I can’t recall whether Bush made an appearance. But nearby Akhunov’s Monument to the Match (detail pictured above) showed a model of the Empire State Building constructed out of matchboxes with pictures of Marx, Stalin, Lenin et al. A single match imitated the building’s spindly spire. Should they all go up in flames? And in an era where year-zero regimes were not how burgeoning democracies sought to do politics, who could be entrusted to light the match? Did such regimes hold the key to their own self-destruction, as this work seemed tentatively to suggest?

Dictators were uppermost in mind in Vyacheslav Akhunov’s red-carpet display Alley of Superstars. Here the painted faces of world leaders, past and present, were imprinted on a red carpet, with each face encircled inside a big, spangly star, like a Hollywood hall of fame: Castro, Franco, Chavez, Stalin, Ceausescu, Pol Pot. Marx was there, too and so was Tony Blair, at which point you wondered whether this reduced the work to a certain platitudinous glibness. The work was made between 2008 and 2012, and I can’t recall whether Bush made an appearance. But nearby Akhunov’s Monument to the Match (detail pictured above) showed a model of the Empire State Building constructed out of matchboxes with pictures of Marx, Stalin, Lenin et al. A single match imitated the building’s spindly spire. Should they all go up in flames? And in an era where year-zero regimes were not how burgeoning democracies sought to do politics, who could be entrusted to light the match? Did such regimes hold the key to their own self-destruction, as this work seemed tentatively to suggest?

In such a light as this, even the Chapmans’ tar-faced, darkly comic Nazis took on a more serious mood. And works that elsewhere could evoke and embrace a whole multitude of meanings here throbbed with particularity. Berlin-based Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota’s After the Dream (main image) featured a receding line of long white dresses afloat in the middle of a darkened room and entwined in a complex cat’s cradle of black cotton. The imprisoning taut black threads resembled both barbed wire and frenzied pencil-marks in the act of scribbling out. One could make a direct connection between this work and Louise Bourgeois’s Cells, some of which could be seen elsewhere in the biennale. Yayoi Kusama’s installation Footprints to the Future, was also bought to mind, her obsessive psychedelic dots threatening to obliterate a whole room.

But the single most outstanding work, certainly the most powerful for me, belonged to Song Dong. In a work entitled Wisdom of the Poor (detail pictured right), he partly recreates, in deeply evocative, poetic form, the living conditions of those in Beijing who dwell in slum-like public courtyards, known as hutongs. In an attempt to try and improve their lives they “borrow” public land and build around it, careful not to break the law by actually destroying anything. One family built a makeshift bedroom over a shrub and let it grown into a tree. The tree grew through a hole in the middle of the mattress, as we see in this achingly haunting installation. It’s an unforgettable work from an artist who recently had his first major UK exhibition at the Barbican’s Curve gallery.

But the single most outstanding work, certainly the most powerful for me, belonged to Song Dong. In a work entitled Wisdom of the Poor (detail pictured right), he partly recreates, in deeply evocative, poetic form, the living conditions of those in Beijing who dwell in slum-like public courtyards, known as hutongs. In an attempt to try and improve their lives they “borrow” public land and build around it, careful not to break the law by actually destroying anything. One family built a makeshift bedroom over a shrub and let it grown into a tree. The tree grew through a hole in the middle of the mattress, as we see in this achingly haunting installation. It’s an unforgettable work from an artist who recently had his first major UK exhibition at the Barbican’s Curve gallery.

Song Dong was one of three artists to win the biennale’s Audience Choice Award along with Kusama and Shiota. Meanwhile, British artist Phyllida Barlow received the Award for The Most Significant Contribution to the Development of Contemporary Art for her installation Rift, a work made specifically for the biennale and featuring dozens of wooden beams tied together with black cloth and surrounded by fallen orange cushions. Perhaps this was an allusion to Ukraine's so-called Orange Revolution, the demonstrations that peacefully overturned the 2004 presidential election, and the regime that has since been in power. But what it might be saying about the situation remained beguilingly elusive.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment