Kiss the Day Goodbye: Marvin Hamlisch, 1944-2012 | reviews, news & interviews

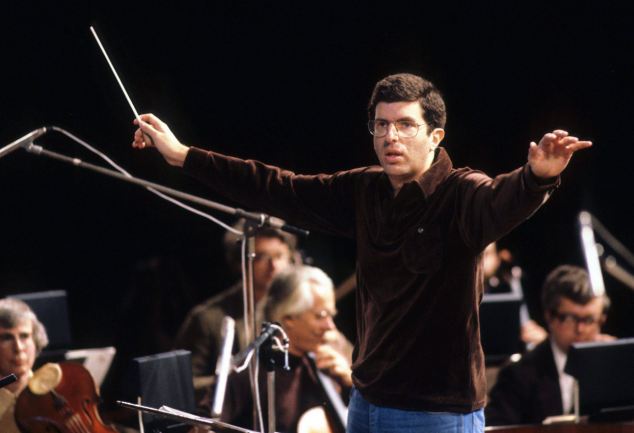

Kiss the Day Goodbye: Marvin Hamlisch, 1944-2012

Kiss the Day Goodbye: Marvin Hamlisch, 1944-2012

Nobody did it better: the speed-songwriter who wrote the music for A Chorus Line

Marvin Hamlisch’s three Oscars all came in 1974. "I think now we can talk to each other as friends," he said as he accepted his third award of the night. He composed the winning song "The Way We Were" (and the film's score) for Barbara Streisand, having started out on Broadway as rehearsal pianist in Funny Girl.

Over the years, a lofty ambition to have 10 Broadway hits, nurtured even as he trained as a classical pianist at the Juilliard in New York, was gradually revised downwards. "What I want to do is have one more show which for me is as innovative as A Chorus Line," he told me when I met him some years ago. "That's what I want. One." "One", coincidentally, is the title of the stirring, aspirational number which closes A Chorus Line, which tells of young hopefuls auditioning for a role in a Broadway show. While he waited there was They're Playing Our Song, based on his relationship with lyricist Carole Bayer Sager, a huge if less musically mould-breaking success on both sides of the Atlantic. The Goodbye Girl, adapted from the 1977 film scripted by Neil Simon, was a slight romantic bauble. In 1983 Jean Seberg went belly up at the National Theatre and never made it back across the water; and then Smile, from the caustic 1975 movie about beauty pageantry, failed to put the eponymous expression on the faces of the few Broadway-goers who caught it. Both shows, he insisted, were good ideas bloodlessly done. He kept their names off his theatrical resumé.

Packaging sizeable self-esteem as geeky schlemiel wit, Hamlisch was a natural talker

"Let me tell you about the word great," he told me. "There are two types of great. One great is you sit down with Michael Bennett [the director of A Chorus Line who died of Aids], you set this incredible goal and you succeed. The other kind of great is you set a very modest goal: we're putting on this show, all we want is people to have a good time. And if you achieve it it's also great, but it's great in a different way."

Packaging sizeable self-esteem as geeky schlemiel wit, Hamlisch was a natural talker and and even more natural composer, kinetically driven by a compulsion he no doubt inherited from his parents, who were Jewish refugees from the Anscluss. He talked, and worked, like an express train. He could write songs at the drop of a hat, the most famous being "Nobody Does It Better", the Bond theme sung by Carly Simon which, he was painfully aware, did not win the Oscar. A popular booking on the cabaret circuit, Hamlisch used to do a medley of "all the greatest songs that have lost the Academy Award. It has ‘Cheek to Cheek’, ‘I've Got You Under My Skin’, and the third one I do is 'Nobody Does It Better’.”

Nobody had a greater facility to write songs - some witty pastiche, some unadulterated schmaltz - and there were awards galore, many of them for his numerous soundtracks: only Richard Rodgers also won an Oscar, a Tony, an Emmy, a Grammy and the Pulitzer Prize. But a return to Broadway's Olympian heights never quite happened. To cite another song from A Chorus Line, he never kissed the day goodbye. "To revisit the mountain without Michael Bennett and without Ed Kleban [the show's lyricist] is very difficult. Most people just go back to their collaborators and say, 'OK let's do it again.' I didn't have that chance. They both died. I'm not giving up. I refuse to give up."

Carly Simon performs 'Nobody Does It Better'

JASPER REES: What is the secret of a great musical?

MARVIN HAMLISCH: The great shows are the ones that broke the formula. West Side Story, that's a great show. From another point of view, you'd say it only ran 14 months. A Chorus Line, there's a case in point: no scenery, no costume.

How early in your life did you realise that writing musicals was what you wanted to do?

Very early. I remember in my sixth grade, I bought the album to My Fair Lady. At the age of 16 I had seen West Side Story five times. I saw Gypsy easily 15 times. On the first show I ever worked on, which was Funny Girl, I was the rehearsal pianist, I was 19 years old, and I would get on that stage and go, "I gotta do this." I think the reason I like Broadway the most is when you do a film it's over. And now you put on the music. You're an adjunct. With a Broadway show, it's manipulation of an audience, and you can change it night to night, so that it's like almost a game. How can me make it so that it's more poignant. It's malleable, you're one of the daddies and mommies. You're a parent. In the other thing you're just a kind of bystander. Where do you want the music. OK I'll be back. You're basically a gun for hire. I'm here, where do you want your carpet?

'One' from A Chorus Line

How talented were you as a kid?

Highly talented, because I had a very good ear. I was born with a fabulous ear. Someone could play something, I could play it right back. My sister was taking piano lessons, the teacher would leave, I was just sitting there listening, not even watching, then I could go to the piano and I could play the notes. It was in the family. My father was a musician. This was not something I worked at all.

Did you work hard at the Juilliard?

You had to. They knew I was talented but it was like I was getting away with murder because of my ear. I was there for 13 years.

I wasn't going to become Horowitz, so I could be normal and be with people

Were they aware of your pop instincts?

They were semi-aware of it but you didn't go around telling anyone. I once asked my father, "If I'm not going to become Horowitz, what am I doing here?" He had a great answer. "If you want to be a composer you have to be able to play your songs really well. For no other reason than that, you better learn how to play." And the Juilliard gave me an entire career based on what I learned there. The Juilliard training was absolutely indispensable to my life.

You gotta be real careful because it's like a parlour game. A kid all of a sudden can do it at the age of seven. And if your parents aren't smart enough to understand you're doing, you become this thing on display. "Come on, do it in another key." My parents were very grounded. They were from Vienna, they cared a lot about education, family life. I love baseball and I would never give up my baseball. And I think also, let's face it, I wasn't going to become Horowitz, so I could be normal and be with people. The great thing about show business is the Horowitzes of the world are lonely. It's you versus yourself. It's you versus a great record that was made by Glenn Gould. It's you, the music, the piano, the end, and occasionally once a week your teacher. What I do it's chorus girls, chorus guys, dancers, singers. You're in a more normalised population.

Were your parents behind you?

My father was able to see that I was going through. My father was more pushing me than my mother but he knew the trials and tribulations of what it is to sit at the piano and do what you do. He played six instruments, particularly the accordion. The stuff he did was basically European stuff. He was always at some European functions, bringing Europe to America. One of my memories which I always loved, he would come home from one of those evenings which would be at the Waldorf Astoria or the Plaza and he would bring two of the desserts home. This was three o'clock. My mother would wake us up and say, "Daddy's home." You'd go into the kitchen and there would be this wonderful dessert that we could never in a million years afford.

How did you meet Liza Minnelli and her mother?

I was a friend of a guy who Liza was dating - 14, 15. There was going to be this Christmas party and during this party Judy Garland asked me to play for her. First of all I knew everything Judy Garland did. In fact she picked a rather obscure song, which was "The Christmas Waltz" by Jule Styne, and I knew it. I said to her, "What key do you want?" She said, "I start off on an F." I said, "You got it." Then I played for her "San Francisco". The big thing of that night was that I had written songs for Liza to sing and this was the first time Judy was going to hear Liza sing. The big thing about that Christmas was that when it was over they sent me home in a limo and I remember calling my mother to tell her that I was going to be late because I was going to take the limo to all my friends and knock on their door and say, "You're never going to believe what I came home in." I wrote a piece of material for her to do in concert with Liza.

Define Hamlischian.

Define Hamlischian.

Hamlischian I think at its best is a good grounded melody, almost old-fashioned, it's melodic and it has emotional appeal. That's it's strength. Most people do think of my music as romantic. It's a little on the old-fashioned side.

Do you smart from the suggestion that A Chorus Line is unhummable?

I think it's a very bad assumption that if something isn't hummable somehow it's not good. Do you think anybody could hum "There's a Place For Us" or "Maria" the first time through? Those are very complicated songs. Sometimes shows should be hummable. In A Chorus Line I tried to write songs that should sound like they were coming instantly out of the character. And sometimes you could hum it and sometimes most of the time you couldn't. I did not try to "write one down the pipe". They're Playing Our Song critically for me did much better music wise than A Chorus Line the first time through. Humming is a bad criterion. Is that the standard we're going to set? If you can hum it it's great. It shouldn't work like that. I think there's too much emphasis on that song that you come out humming. The thing is that if you have an emotional experience in the theatre, that's the home run. That's the hummable part. The hardest thing is not to write a hummable song. The hardest thing is to write a show in which people are moved by it. I don't set out to write a hummable tune.

That said, what is your most hummable tune?

It's not hummable but actually it became a hit. "The Way We Were". Very tough song. The most hummable song I ever wrote was "They're Playing Our Song". I used to say, "People can hum that before they hear it." Sometimes what happens with plagiarism is you don't do it knowingly normally. Sometimes you just hear something out of the jukebox and then five years later that melody crops and you honestly believe you wrote it. It turns out, whoops. I'm amazed there isn't as much plagiarism as there is. There's only 12 notes, folks.

If your standard is A Chorus Line you might as well go catatonic. You might as well never write again

At its best composing should be 100 per cent inspiration and zero per cent anything else. How many times does that happen? Once every billion years. So what composing really turns out to be your own technique, which is about 40 per cent, hopefully 55 per cent inspiration. And the rest pure luck. As long as you're 50.1 percent in the inspiration category you're OK. Get anywhere beneath it you're banal. As a professional you can get to 40, 45, because "Hey, I've been doing this a long time". It's that extra little bit you just pray that it's in the cards.

Why didn't you do Jean Seburg well enough?

If the plane goes down do you blame the pilot, do you blame the guy who made the engine, do you blame the co-pilot? The show that we showed Peter Hall in New York was a show I liked. It needed work but I liked it. It was a very straightforward show. The show that we opened with here had during rehearsal taken on some gimmicks and some bits. Interesting but it didn't really help the telling of the story. Clarity is so important. What sometimes happens is you become sick of it, you've been doing it so long, so in a strange way you start doing the variations before anyone saw the theme. I think that Jean Seburg, though I think it's a wonderful idea, got fuzzy. You gotta be able to bite into it. This was cotton candy after a while. You know as you're going it that you're going the wrong way. After you start previewing there are certain things you can fix, a song or a piece of dialogue. You can't fix a concept gone wrong. What you'd have to do is to stop everything, which now they do. You shut down, you lose a lot of money, and then you start up again. That is the luxury of being Andrew Lloyd Webber.

Has your goal been to repeat the Himalayan achievement of A Chorus Line?

I know that you're not going to hit it every time. They're Playing Our Song wasn't an attempt to do A Chorus Line. Sometimes you get on a project and you know you're not going to do it. Very quickly after I did A Chorus Line there was a little television movie I was going to do and I called Ed Kleban and said, "Ed, we can do this thing." He said no. I said "Why not?" He said, "It ain't going to be as good as A Chorus Line. Forget it. I'm not going to do it." If your standard is A Chorus Line you might as well go catatonic. You might as well never write again. I like to work. I'm a worker. So therefore I'm not going to sit on the sidelines and wait until all of these factors come together. But in me is this desire to do great. Sometimes you do great and you write a good song. Some things have an aura of greatness, and some things have an aura of simple. It doesn't mean that within the simple it can't be great. When A Chorus Line opened after about five, six, seven days, all my desire was let's do it again. If you ask me what I really want to repeat, it's that stimulating feeling that you got when you were in the room with the Chorus Line people. My favourite musical West Side Story I think only lasted 18 months on Broadway. I'll take those 18 months, as opposed to 18 years, if you give me West Side Story. It's that kinetic energy that I look for, it's that thing that goes, “I'll stay up three nights in a row because this is great.”

Streisand sings 'The Way We Were'

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment