Akram Khan, Solos, Sadler's Wells | reviews, news & interviews

Akram Khan, Solos, Sadler's Wells

Akram Khan, Solos, Sadler's Wells

Even with a fractured arm, the contemporary Kathak star is still a miracle dancer

What do you call a dancer with a fractured shoulder and only half a show to offer, who nevertheless takes you to the outer reaches of dance nirvana? It can only be Akram Khan. Now fêted as a (reasonable) contemporary choreographer, the favourite of Kylie, Juliette Binoche, Sylvie Guillem, Khan is too little celebrated for what he does at a level beyond anything most of us are ever likely to see, which is dancing in his magnificent, complex, disturbing traditional Indian form of Kathak.

Four weeks ago he was intending to prepare for Sadler’s Wells a new contemporary dance premiere, Gnosis, to launch its imaginative festival of dance and music last night, which he and Nitin Sawhney are curating. Gnosis would be the second half of an evening in which he would display his Kathak credentials: the old and new sides of him. But a left shoulder fracture put paid to that, and only a week ago he was still in a sling.

Despite having to cancel the premiere, still the man danced Kathak like a god, humbly determined to serve his packed house. The hastily edited show was billed to last only an hour, but in the event he gave us almost half as much again (and I hate to think how that shoulder was feeling).

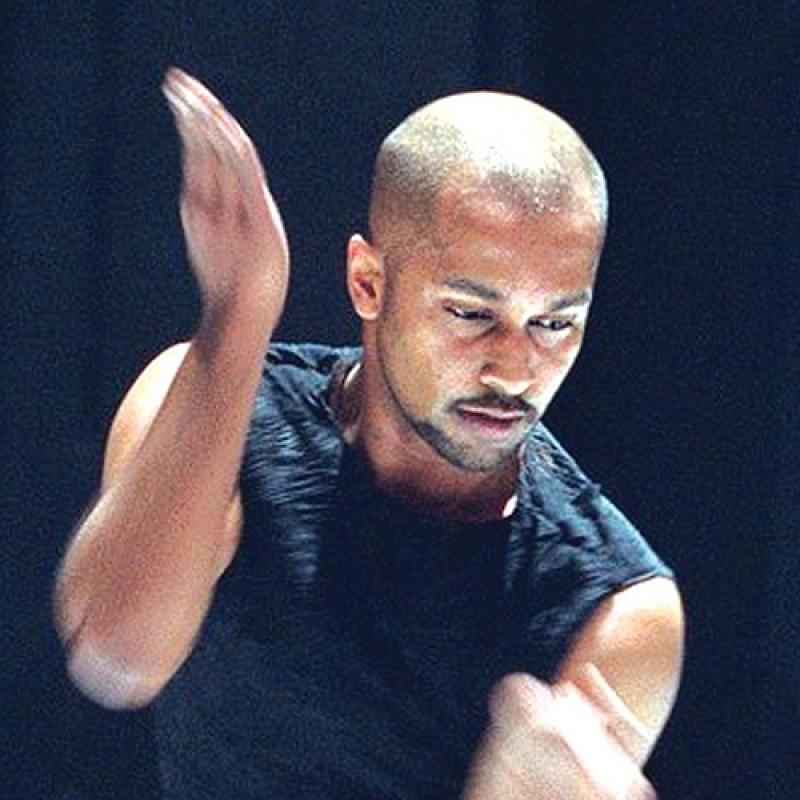

The thing about Akram in Kathak is that there is no point at which you can say “this is music, and that is dance” - his ears and feet are intricately linked to produce syncopational delights with slapping bare soles and heels, his arms and eyes switch through unbelievable directional changes at lightning speed almost like a dog chasing its tail, his vocalising seems inextricable from an urge to move that wells up from deep in his body. His first solo was 15 minutes long, at least - a feat of stamina alone equivalent to running several miles, and filled with extremes of silken soft undulations and dagger-sharp, glinting jags and jabs, with dazzling spins and helter-skelter rushes across the stage that evoke thoughts of lovers, knights, dashing poets.

It began with whispering ankle bells in the dark, as a fine girl Japanese drummer showed every colour of percussive dynamic possible with two sticks on two skins, from a barely audible shiver to an explosive fortissimo roll. Khan appeared, his shaven head gleaming, a monkish figure in olive-grey tunic, with thick anklets of bells. With one raise of an arm and a very slight inhalation through his entire body, he commanded the stage - it’s that instinctive in-breath, which reveals his own anticipation and moment of self-dedication, that gives the thrill. A kind of obeisance to his art, I think, which you feel with only the very few, very great artists.

That magnificent solo, Polaroid Feet, was choreographed and (tellingly) composed in 2001 by Gauri Sharma Tripathi, a regular supplier to Khan of traditional Kathak material for his unique fusion of musical dance. In his improvisation later, one was more conscious of being shown simple building blocks and a slow gathering of rhythmic like-mindedness with his musicians, as he vocalised patterns at a microphone that they picked up on their percussion, or smacked his feet faster to whip them along. Once he’d set a pace, off he’d dart in an improvisation, like showing virtuosic studies for technique - a whirl of unbelievable pirouettes, or long tender undulations like a breeze through a wheat field.

Akram's drummers are mathematicians, and they like nothing better than being thrown a skein of numbers to calculate rhythmic possibilities

The music-making was also fascinating. As Akram said, his drummers are mathematicians, and they like nothing better than being thrown a skein of numbers to calculate rhythmic possibilities with their fingers and sticks. The taiko girl, Yoshie Sunahata, featured in an immaculately exciting trio with Sanju Sahai on tabla and Manjunath B Chandramouli on mridanga. Another musical interlude seemed to be composed of only five descending notes, and yet the continual changes in pulse, Faheem Mazar’s lamenting voice, the detailed variety in Soumik Datta’s plucking of his sarod strings, the cornucopia of tabla timbres, all this turned a restrained theme into a highly varied journey of mood. (Note to Sadler’s Wells: why can’t we have surtitles for Kathak song, which like flamenco is a soulfully literate lyrical form?)

Then a surprise: Akram declared that if he couldn’t perform his new piece, he could at least do an abridged arrangement of the final scene, where the blind princess Gandhari dies. We were in for a shock. While Sunahata sang with eloquent sadness alongside him, Khan turned all that stupendous articulation and control of his, which we had just seen so dazzlingly transfigured into light, fluidity and momentum, into a fearful visualisation in dance of the slow breakdown of all that into quivers, jitters and gibbers, a blur of disintegration that came to a sudden stop, as if the instant when spirit left matter. It felt like watching death. The full work is now to be premiered next spring at Sadler’s Wells.

- Akram Khan joins Nitin Sawhney for a music-dance premiere Confluence at Sadler's Wells, 26-28 November; the Svapnagata festival, until 28 November, includes performances by musicians and dancers. Book online here

- Check out what's on at Sadler's Wells this season

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Add comment