Schwitters in Britain, Tate Britain | reviews, news & interviews

Schwitters in Britain, Tate Britain

Schwitters in Britain, Tate Britain

Forgotten German emigré or imaginative fireball who influenced British art? The last eight years of a creative life examined

The Pop Art collages of Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi and, more recently, the wayward sculptures and installations of artists like Phyllida Barlow would be unthinkable without the inspirational presence in Britain of Kurt Schwitters. Yet the German emigré is hardly a household name.

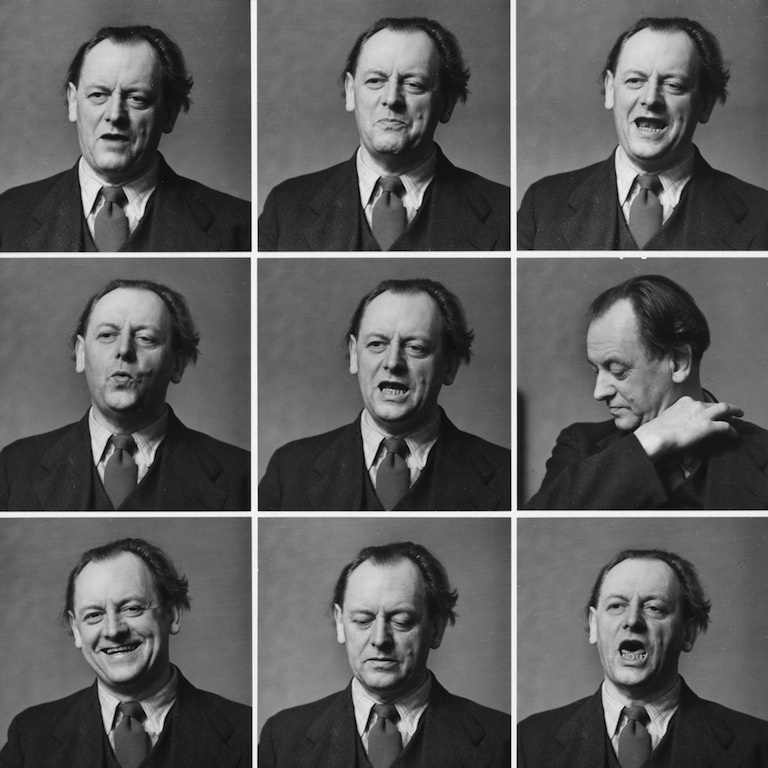

The Tate exhibition Schwitters in Britain hopes to put that right by showing the full range of his work. These include reliefs and collages made from detritus picked up off the street; oddball sculptures fashioned from plaster, wood, stone, metal or bone; grotto-like installations that crept across walls and ceilings to engulf the space; and abstract poems like the Ursonate, performed by the artist in London in 1944 (pictured below right) which involved humming, singing and chanting nonsensical sounds. Finally, there were the realist portraits and impressionistic landscapes, which he produced to sell and are usually dismissed as pot-boilers. With this overview, the Tate hopes to demonstrate that, far from a miserable saga of poverty and obscurity, the eight years that Schwitters spent in Britain before his death in 1948 were extremely productive.

He wasn’t here by choice. Having been included in the infamous exhibitions of Degenerate Art staged by Hitler to pour scorn and put pressure on artists considered politically suspect, Schwitters fled Nazi Germany in 1937, leaving his wife behind to look after their elderly parents and property. He took refuge in Norway with his son and daughter-in-law, and when the Germans invaded three years later, the family escaped on the last icebreaker bound for Britain.

He wasn’t here by choice. Having been included in the infamous exhibitions of Degenerate Art staged by Hitler to pour scorn and put pressure on artists considered politically suspect, Schwitters fled Nazi Germany in 1937, leaving his wife behind to look after their elderly parents and property. He took refuge in Norway with his son and daughter-in-law, and when the Germans invaded three years later, the family escaped on the last icebreaker bound for Britain.

On arrival, he was interned as an enemy alien with numerous other artists on the Isle of Man. They didn’t allow the scarcity of materials to stop them making art and staging exhibitions, though. To earn a few bob, Schwitters painted portraits on old bits of linoleum; and although lively enough, his likenesses of fellow inmates such as Fred Uhlman wouldn’t earn him a place in the pantheon of modern art. Had they survived, though, his sculptures might have. Uhlman recalls Schwitters’s makeshift attic studio as having “a musty, sour, indescribable stink which came from three Dada sculptures which he had created from porridge, no plaster-of-Paris being available. The porridge had developed mildew and the statues were covered with greenish hair and bluish excrements of an unknown type of bacteria.”

Later, Schwitters would go on to make small plaster sculptures like 1945's Opening Blossom (pictured left), using paint to emphasise the form. Reminiscent of work by Arp, Hepworth, Gabo and Gaudier Brzeska, with their simple fluid shapes they are typical of their time. But when he used bits of bone, wood or metal to create angular discontinuities and painted them to contradict rather than clarify the form, the wonderfully oddball results not only seem way before their time, but anticipate the "hand-held" sculptures of Franz West and the ad hoc assemblages of Phyllida Barlow. He was right when he wrote to his friend Moholy-Nagy: "I believe that at the moment my best things are my small sculptures."

Later, Schwitters would go on to make small plaster sculptures like 1945's Opening Blossom (pictured left), using paint to emphasise the form. Reminiscent of work by Arp, Hepworth, Gabo and Gaudier Brzeska, with their simple fluid shapes they are typical of their time. But when he used bits of bone, wood or metal to create angular discontinuities and painted them to contradict rather than clarify the form, the wonderfully oddball results not only seem way before their time, but anticipate the "hand-held" sculptures of Franz West and the ad hoc assemblages of Phyllida Barlow. He was right when he wrote to his friend Moholy-Nagy: "I believe that at the moment my best things are my small sculptures."

Schwitters finally arrived in London after 17 months in Hutchinson Camp, by which time fellow artists like Moholy-Nagy and Naum Gabo, who’d also fled Germany, had left for Cornwall and the States, respectively. Wartime London was not an easy place to make a new start and, despite establishing valuable contacts, being included in several mixed shows and given a solo exhibition, Schwitters was unable to make a living. He had a stroke which caused temporary paralysis, learned that his wife had died, and that his Merzbau – a cardboard and wood installation, which spread across six rooms of his Hanover apartment and which he considered his life’s work – had been destroyed by Allied bombing.

In 1945, he left London for the Lake District but, far from being a sick and lonely outsider worn down by disappointment, he had a new partner, Edith Thomas, became involved in the local art scene, was busy painting landscapes and portraits to commission, and began covering the walls of a small barn near Elterwater with a new Merzbau, which was funded by the Museum of Modern Art, New York where he also planned to exhibit.

In 1945, he left London for the Lake District but, far from being a sick and lonely outsider worn down by disappointment, he had a new partner, Edith Thomas, became involved in the local art scene, was busy painting landscapes and portraits to commission, and began covering the walls of a small barn near Elterwater with a new Merzbau, which was funded by the Museum of Modern Art, New York where he also planned to exhibit.

And the impression that one gets from the work is of someone with a new lease of life. Collages like En Morn (1947, main picture) are simpler, clearer and more optimistic. The muddy blues, greens and blacks of the pre-war German paintings, collages and reliefs have given way to brighter colours and a much lighter, more humorous touch (pictured right, Anything with a stone, 1944). The few drawings included are full of vitality and, although far from ground-breaking, the landscapes are filled with an energy that celebrates the elements (one can almost feel the wind gusting about) and belies the increasing infirmity of the artist.

Because so much of his work was destroyed both during the chaos of war and by the Nazis, we shall never have a full picture of Schwitters’s achievements, but this exhibition gives us a glimpse of this indomitable pragmatist who, by making the most of challenging circumstances, was able to carry on planning and producing to the very end. And his collages and small sculptures alone make him well worth celebrating.

Listen to Kurt Schwitters reciting Ursonate

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment