theartsdesk in Mali: Creation, Conservation and Restoration | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Mali: Creation, Conservation and Restoration

theartsdesk in Mali: Creation, Conservation and Restoration

The battle to bring Mali's architectural and religious history into the digital age

Timbuktu, the legendary "End of the World", does actually exist, and as everyone now knows, it's in Mali. It has just been thrust into the world’s focus after its recent liberation from the Al Qaeda-linked extremists who have occupied the north of Mali during the last 10 months.

Timbuktu’s ancient mosques are protected by their UNESCO World Heritage status. It is the "city of the 300 saints", which is one detail that did not please its recent jihadist occupiers who did not agree with the worship of saints as practised by Timbuktu's population. Many of the town’s mausoleums were therefore destroyed. In addition, as a final flourish the jihadists set light to the ancient Arabic manuscripts which had been stored at the Ahmed Baba Institute, a state establishment for the preservation of Malian manuscripts.

Irina Bukova, the UNESCO cultural envoy, accompanied France's President Hollande on his triumphant entry into Timbuktu on 2 February, after French troops had liberated the town (Timbuktu's Sankore mosque, pictured right). The pair carried out an inspection of what had been destroyed and Mme Bukova vowed to come up with funding for the rehabilitation of the town, since announced as €5m.

Irina Bukova, the UNESCO cultural envoy, accompanied France's President Hollande on his triumphant entry into Timbuktu on 2 February, after French troops had liberated the town (Timbuktu's Sankore mosque, pictured right). The pair carried out an inspection of what had been destroyed and Mme Bukova vowed to come up with funding for the rehabilitation of the town, since announced as €5m.

This is all very commendable, of course. The people of Timbuktu suffered grievously under the Islamist occupation and need every encouragement. However, as an expat living in Djenne, Mali where I have a hotel (www.hoteldjennedjenno.com), I confess to a somewhat jaundiced view of how such overseas funding might be spent.

Firstly, the mausoleums which UNESCO will reconstruct: about 80 per cent of these are made of sun-dried mud brick which is then plastered with mud. Some are built with the characteristic Timbuktu stone. But in both cases, I do hope that UNESCO will let the people of Timbuktu reconstruct these mausoleums themselves. The cost of rebuilding a traditional mausoleum in local material and using local masons is negligible. But more importantly, it is surely the pride of the city and something the people would like to do themselves? I fear that UNESCO will be sending in "experts" in 4x4s.

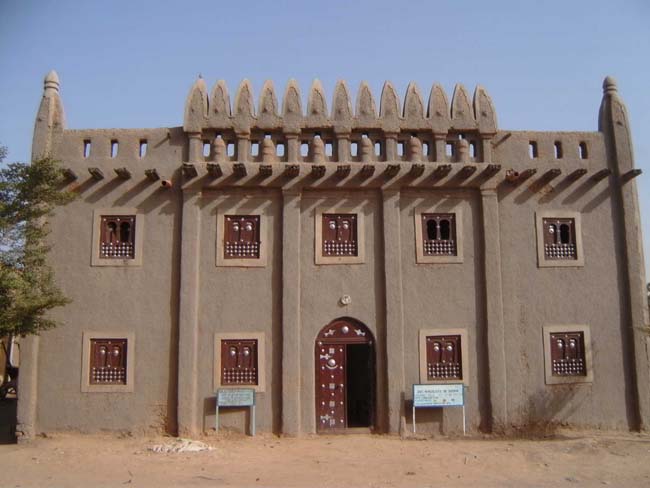

There is a museum in Djenne which was built a few years ago with European Community money. This museum has still not opened and has no exhibits. This is a scandal, and the reasons why it is still not open remain shrouded in mystery. Designed by a Bamako architect, it was built with mud in the traditional Djenne style and is a very handsome building. The masons of Djenne were employed as "advisers" or as labourers. Why? Because they cannot read and they cannot find their way through the labyrinth of bureaucracy which has to be conquered before being employed by the European Community. The fact that they and their ancestors were the very ones that invented this building style seems to hold no importance (the Djenne Manuscript Library, pictured above).

There is a museum in Djenne which was built a few years ago with European Community money. This museum has still not opened and has no exhibits. This is a scandal, and the reasons why it is still not open remain shrouded in mystery. Designed by a Bamako architect, it was built with mud in the traditional Djenne style and is a very handsome building. The masons of Djenne were employed as "advisers" or as labourers. Why? Because they cannot read and they cannot find their way through the labyrinth of bureaucracy which has to be conquered before being employed by the European Community. The fact that they and their ancestors were the very ones that invented this building style seems to hold no importance (the Djenne Manuscript Library, pictured above).

Mali's historic manuscripts, overleaf

And that's not all. Every year this monumental building, like all of Djenne’s mud buildings including its spectacular mud mosque, need to be replastered with mud (there are always repairs needed somewhere on a mud building). Every year, an estimate by the Djenne masons is sent off with the estimated cost to repair the damage. The total may be equivalent to about €460, and every year it is rejected as being too small a figure. The powers that be believe they need to send up "experts" from Bamako first of all to make a report, then to make a proposal and so on. Just one trip to Djenne from Bamako in a 4x4, including lodging, experts’ fees etc, will come to a figure much higher than the quote for the repair!

As for Timbuktu's historic manuscripts (an example pictured right), Timbuktu has been awash with funding for them for decades. They have had money from the Mellon Foundation and the Ford Foundation in the USA, the Andalucian regional Government in Spain, funding from the State of South Africa, from Bahrain, from Lyon in France, from Norway and from Luxembourg. They have state-of-the-art digitizing equipment worth possibly millions of Euros. Yet Abdul Wahid Haidara, the director of Mohammed Tahar Library of Timbuktu, estimates that no more than about two per cent of the Timbuktu manuscripts have been digitized.

As for Timbuktu's historic manuscripts (an example pictured right), Timbuktu has been awash with funding for them for decades. They have had money from the Mellon Foundation and the Ford Foundation in the USA, the Andalucian regional Government in Spain, funding from the State of South Africa, from Bahrain, from Lyon in France, from Norway and from Luxembourg. They have state-of-the-art digitizing equipment worth possibly millions of Euros. Yet Abdul Wahid Haidara, the director of Mohammed Tahar Library of Timbuktu, estimates that no more than about two per cent of the Timbuktu manuscripts have been digitized.

Now UNESCO intends to give them even more money, particularly for digitizing. Meanwhile here in Djenne we also have very large deposits of ancient Arabic manuscripts. They are stored at the Djenne Manuscript Library (www.djennemanuscrits.com). Djenne is traditionally thought of as the "twin city" of Timbuktu. It enjoys the same glorious past as an important city of learning and commerce, but alas not the financial clout of its more famous twin sister.

However, the library was given a grant of £55,000 from the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP) in 2011 for a two-year project of digitization which will end in July. We have already digitized over 120,000 images of the ancient manuscripts of Djenne, quite possibly a larger number than Timbuktu ever managed to do. These images have just been delivered safely on a hard drive to the British Library in London as a safety measure because of the continuing unstable situation in Mali.

However, the library was given a grant of £55,000 from the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP) in 2011 for a two-year project of digitization which will end in July. We have already digitized over 120,000 images of the ancient manuscripts of Djenne, quite possibly a larger number than Timbuktu ever managed to do. These images have just been delivered safely on a hard drive to the British Library in London as a safety measure because of the continuing unstable situation in Mali.

There has been a resistance to digitization in Mali. This has to do with a fundamental difference in perspective on learning and the written word between the West and this traditional Islamic society. We look upon learning as something that is freely given: libraries should be open, knowledge should be shared and should be free and easily available. Here the talibes (religious students) learn to recite the Koran by rote in the many Koran schools. They are not told what they recite. They are not allowed to know until they can recite faultlessly. Only then have they earned the right to know. Knowledge is given discriminately, and it has to be earned (author Sophie Sarin with Djenne's chief muezzin Alphamoye Nientao, pictured below).

Timbuktu is notoriously difficult for scholars. It is hard to gain access to the documents, many of which have a "secret knowledge" status. It has not been possible to copy documents in Timbuktu, and digitization work in such a climate is only carried out with difficulty. It is also a question of financial gain. The private libraries of Timbuktu fear that if their manuscripts are digitized, people will no longer come to visit their library and pay the fee.

Timbuktu is notoriously difficult for scholars. It is hard to gain access to the documents, many of which have a "secret knowledge" status. It has not been possible to copy documents in Timbuktu, and digitization work in such a climate is only carried out with difficulty. It is also a question of financial gain. The private libraries of Timbuktu fear that if their manuscripts are digitized, people will no longer come to visit their library and pay the fee.

However, with the recent events in Timbuktu this attitude is likely to have been modified, and digitization programmes will start, with the funding about to arrive. Here in Djenne we are hoping that just a fraction of all this funding might come our way so we can continue our important digitization work, as well as starting other initiatives such as the conservation and the cataloguing of the Djenne manuscripts.

- Sophie Sarin is Project Leader of Endangered Archives Programme no 488, Djenne Manuscript Library

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Bryony Kimmings, Soho Theatre Walthamstow review - captivating tale of the cycle of life

Witty ode to Mother Nature

Bryony Kimmings, Soho Theatre Walthamstow review - captivating tale of the cycle of life

Witty ode to Mother Nature

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Free Association launch review - strong start for improv company

Troupe moves into permanent home

The Free Association launch review - strong start for improv company

Troupe moves into permanent home

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Add comment