Chuck Close Prints: Process and Collaboration, White Cube Bermondsey | reviews, news & interviews

Chuck Close Prints: Process and Collaboration, White Cube Bermondsey

Chuck Close Prints: Process and Collaboration, White Cube Bermondsey

Close clearly relishes unveiling the method behind the illusion, the trickery behind the magic

Chuck Close is often described as a photorealist. It’s a fair description. His paintings often look like photographs, and he came to prominence in the late Sixties, when photorealism was the rage. At first his huge heads were scaled-up painted transcriptions of black and white photos, such as Big Self-Portrait, 1968, which is the painting you’ll find in most art history accounts of the period. It captures a kind of rough diamond Easy Rider persona.

For those who are fair-to-middling, or simply a bit nothing, in their opinion of Close, they will, I believe, be deeply impressed by this travelling survey of Close’s prints (it’s been touring America for the past decade). Featuring some 150 works, the exhibition documents just how involved, complex and labour-intensive many of his processes are and just how much manipulation an image undergoes at various stages of its making. And as the title suggests, it’s a collaborative process. Close works with a team of master printmakers and it’s a real eye-opener to be introduced to the range of techniques, some very old, some relatively new and experimental, and some arrived at simply by chance and accident, that he has explored throughout his career.

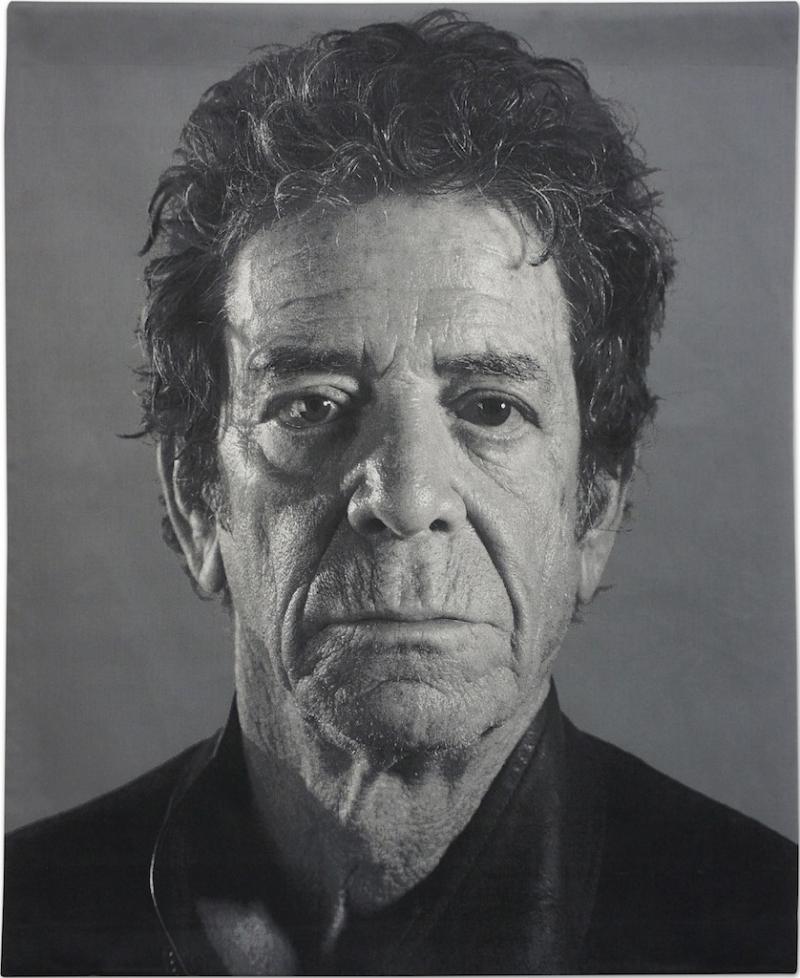

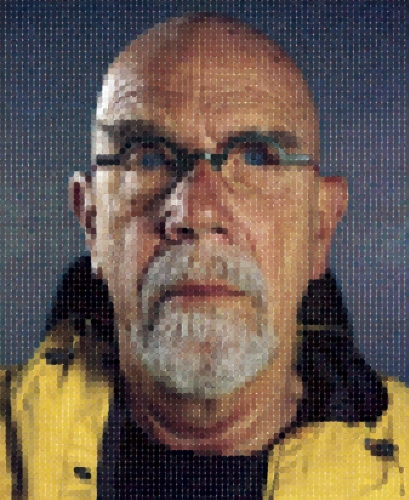

This museum quality show takes us from the velvety mezzotints of Keith, his earliest foray into print-making, to the startlingly photo-like tapestries featuring Lou Reed (main picture) and Roy Lichtenstein. Etchings, engravings, Japanese wood-block prints, grey-scale paper pulp editions, silkscreens, and bulkily built-up collages – each process is ceaselessly explored for its range of possibilities. Often the same image will undergo the same process again and again, varying in tone, depth, texture. Like his gridded lozenge paintings, individual cellular units coalesce to form the image as you move further away, taking us from abstraction to representation. Close clearly relishes unveiling the method behind the illusion, the trickery behind the magic, if you will, and so do we (pictured above right, Self-Portrait / Felt Hand Stamp, 2011)

This museum quality show takes us from the velvety mezzotints of Keith, his earliest foray into print-making, to the startlingly photo-like tapestries featuring Lou Reed (main picture) and Roy Lichtenstein. Etchings, engravings, Japanese wood-block prints, grey-scale paper pulp editions, silkscreens, and bulkily built-up collages – each process is ceaselessly explored for its range of possibilities. Often the same image will undergo the same process again and again, varying in tone, depth, texture. Like his gridded lozenge paintings, individual cellular units coalesce to form the image as you move further away, taking us from abstraction to representation. Close clearly relishes unveiling the method behind the illusion, the trickery behind the magic, if you will, and so do we (pictured above right, Self-Portrait / Felt Hand Stamp, 2011)

His exploration of the face, his own and that of his friends, is almost brutal in its hunger to interrogate every line and sag amid the pitted surface. And he gets pitilessly close to his subject. Squared off and isolated, nothing detracts from the face. Reed looks like some menacing lizard man, Philip Glass, another good friend, looks as if he’s sizing us up in return. Mouth slightly open, eyes heavy-lidded, Glass’s scaled-up visage looks down at us as we look up, feeling a little small in comparison. It’s a face that appears kinder the craggier it’s got, whereas Reed just looks perennially scary.

Unlike Warhol’s Superstars, in which the concentration of the lens for minutes at a time strips the subject of its mask, in Close’s work we interrogate the mask presented in a snapshot that took a second to take. But the snapshot remade reveals its own fascinations. The face becomes vast, virgin territory and we its explorers. Don’t miss this show.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Comments

Great review! One note -- the