Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show | reviews, news & interviews

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Last month a portrait of Alan Turing by AI robot AI-Da sold at Sotheby’s for $1.08 million – proof that, in some people’s eyes, artificial intelligence can produce paintings worth as much as those made by human hands.

Depending on your view of AI, this can either be a very exciting or deeply depressing idea; whichever way you lean, it makes Tate Modern’s exhibition of work by the pioneers of machine art extremely timely.

This exhaustive (and exhausting) show starts in the 1950s with Japanese artist Atsuko Tanaka. In response to the neon signs brightening up Osaka’s streets in the aftermath of World War II, she created a heavyweight dress made of neon tubes and industrial light bulbs. In a series of charming drawings (pictured below) showing heat spots and electric circuitry, she then reflected on the experience of wearing this potentially lethal garment. Next comes a room devoted to the Signals Gallery that opened in London in 1964 as a space "dedicated to the adventures of the modern spirit". On show is one of Takis’s sound machines; it emits gentle, tinkling sounds as an electro magnetic field switches on and off prompting a metal needle to tremble against taut strings. David Medalla’s Sand Machine weaves similarly magical poetry. As it revolves, a motor-driven string of beads leaves a circular trail in a bed of white sand. Whereas Takis’s sculpture is neatly efficient, Medalla’s assemblage is a deliberately wonky contraption consisting of a silver birch branch, bamboo rods and lengths of tangled wire. In each case, though, the machine is harnessed to project delicacy or vulnerability rather than strength and optimism; and therein lies their charm.

Next comes a room devoted to the Signals Gallery that opened in London in 1964 as a space "dedicated to the adventures of the modern spirit". On show is one of Takis’s sound machines; it emits gentle, tinkling sounds as an electro magnetic field switches on and off prompting a metal needle to tremble against taut strings. David Medalla’s Sand Machine weaves similarly magical poetry. As it revolves, a motor-driven string of beads leaves a circular trail in a bed of white sand. Whereas Takis’s sculpture is neatly efficient, Medalla’s assemblage is a deliberately wonky contraption consisting of a silver birch branch, bamboo rods and lengths of tangled wire. In each case, though, the machine is harnessed to project delicacy or vulnerability rather than strength and optimism; and therein lies their charm.

The machines made by Swiss artist Jean Tinguely test the idea of vulnerability to its limits. Many were designed to self-destruct and on display is one too fragile to function. If it were to crank into action, numerous spindly wheels would make a series of little cardboard sails flutter like butterfly wings. Convoluted mechanics produces piffling results. Funny, ridiculous and deeply moving, his wobbly DIY constructions are like metaphors for life. They exemplify the inevitability of failure along with the absurdity (and necessity) of striving against the odds.

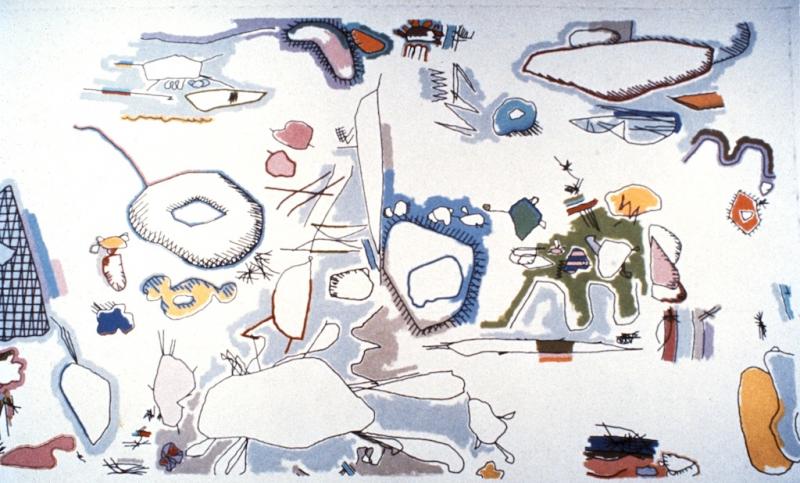

Some 25 years later, the painter Harold Cohen developed AARON, a computer programme that could generate drawings which he enlarged, painted onto canvas and filled with colour (main picture). But AARON got a tad too clever, so Cohen modified it to produce shapes that looked less precise and more like hand drawn images. As with the sculptures described above, the imperfection (or apparent humanity) makes the results disarming and apparently meaningful, because we relate to them. As Cohen discovered, when a machine takes control or the programming gets too clever, the results become less interesting.

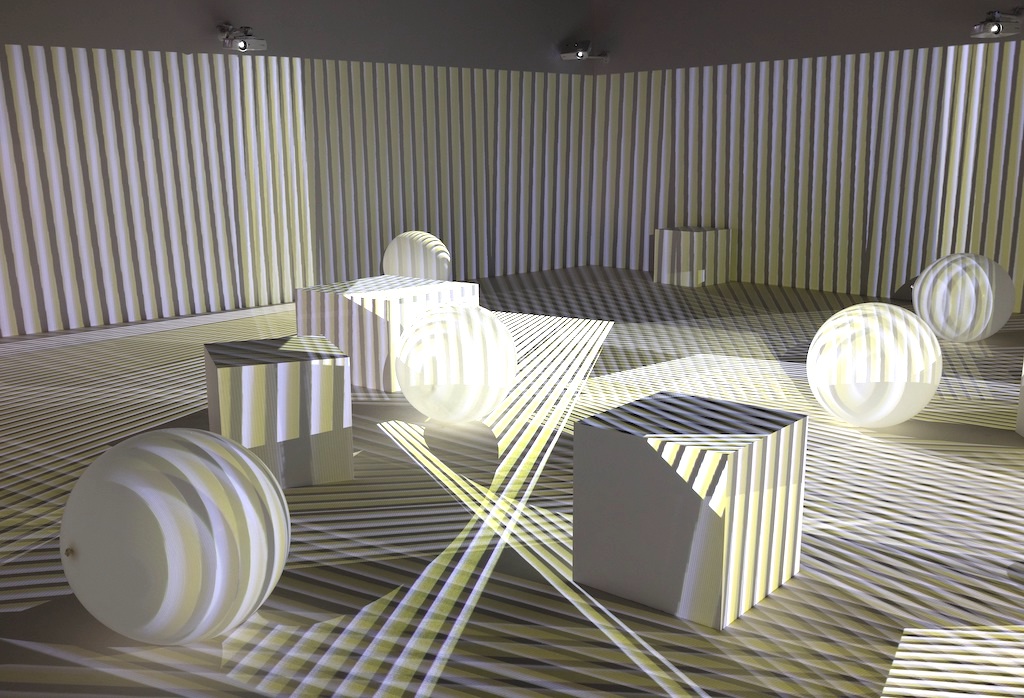

A whole room is devoted to Environnement Chromointerférent, 1974 (pictured below), an installation by Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez. Projected onto walls, floor and the spheres and cubes, which are dotted around the space, interference patterns alter the appearance of everything in their path. To me this is nothing more than a demo of optical effects, useful for the study of human perception but little else. Like airport art, it is devoid of thought or emotion. Cruz-Diez outlines the limitations perfectly when he says: “In my works, nothing is left to chance; everything is intended, planned, and programmed. Liberty and emotions are only present when choosing colours, a task with only one self-imposed restriction: to be efficient.” Yet he has been heralded as “one of the greatest artistic innovators of the 20th century”.

A whole room is devoted to Environnement Chromointerférent, 1974 (pictured below), an installation by Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez. Projected onto walls, floor and the spheres and cubes, which are dotted around the space, interference patterns alter the appearance of everything in their path. To me this is nothing more than a demo of optical effects, useful for the study of human perception but little else. Like airport art, it is devoid of thought or emotion. Cruz-Diez outlines the limitations perfectly when he says: “In my works, nothing is left to chance; everything is intended, planned, and programmed. Liberty and emotions are only present when choosing colours, a task with only one self-imposed restriction: to be efficient.” Yet he has been heralded as “one of the greatest artistic innovators of the 20th century”.

The crux of the matter is whether or not you believe art should be an expression of what it means to be human – to think, feel, strive, suffer, hope, achieve and inevitably fail. If so, the art made by machines and people trying to behave like them will inevitably seem facile because it has none of these qualities.

At the ICA in 1968 Jasia Reichardt curated Cybernetic Serendipity, a show of art generated by or with the help of machines. In an excerpt from the BBC programme, Late Night Line Up she explains how using a computer “enables anybody who can’t draw to create a pretty picture.” If you can’t make it, fake it!

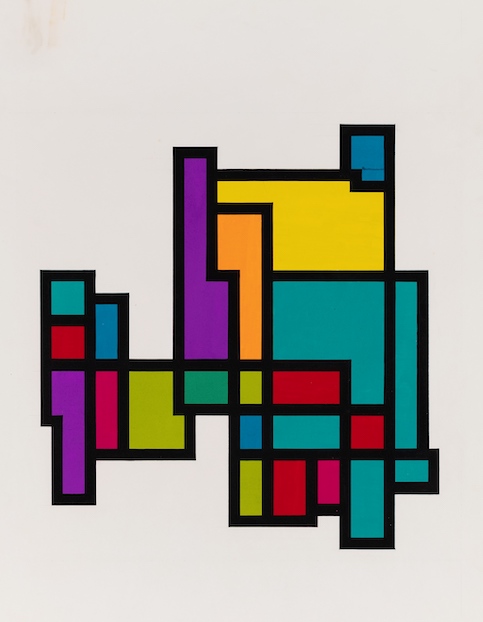

Hiroshi Kawano has created an algorithm that produces computer generated versions of Mondrian paintings. Whereas the originals are encrusted with thick paint (a result of the artist’s efforts to achieve the right balance of lines and colours) KD 29 - Artificial Mondrian, 1969 (pictured above left) is a smoothly anonymous surface bereft of nuance, subtlety, originality or effort – a completely pointless exercise revealing only the difference between art and decor. Optimism – the belief that machines could solve all our problems – probably prompted Reichardt’s and Kawano’s enthusiastic embrace of technology. I remember, in the 1990s, picking my way round an installation by Japanese artist Tatsuo Miyajima. Filling the floor were tiny clusters of LED numbers that clicked as they inexorably counted the seconds. I was transfixed; I felt as if my life were ticking away, as if these little machines were counting down the time I had left on earth. “It is not about creating a beautiful image,” Miyajima has said of his installations, “but a spiritual concept.” Yet encountering the two works on display at Tate Modern – a circle and radiating lines of LED numbers – I saw images, but no concepts.

Optimism – the belief that machines could solve all our problems – probably prompted Reichardt’s and Kawano’s enthusiastic embrace of technology. I remember, in the 1990s, picking my way round an installation by Japanese artist Tatsuo Miyajima. Filling the floor were tiny clusters of LED numbers that clicked as they inexorably counted the seconds. I was transfixed; I felt as if my life were ticking away, as if these little machines were counting down the time I had left on earth. “It is not about creating a beautiful image,” Miyajima has said of his installations, “but a spiritual concept.” Yet encountering the two works on display at Tate Modern – a circle and radiating lines of LED numbers – I saw images, but no concepts.

Maybe my responses were numbed by sensory overload, by too many flashing lights, beeps and buzzes that may be diverting, but quickly pall. Or maybe the optimism once felt by me and others has been replaced by fear and cynicism. AI now seems as much a threat as a boon. I don’t welcome the replacement of artists, writers, actors and musicians by robots, since we learn and grow by sharing actual experiences rather than their facsimile. If we are only fed algorithm-induced simulations, our ability to recognise and empathise with raw feelings and thoughts is bound to atrophy.

I left the exhibition feeling profoundly depressed.

- Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet at Tate Modern until June 1 2025

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment