George Bellows: Modern American Life, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

George Bellows: Modern American Life, Royal Academy

George Bellows: Modern American Life, Royal Academy

An artist who makes us appreciate that long before the Abstract Expressionists American painting had come into its own

One can immediately see the influence of Manet and Whistler, especially Whistler, the fellow American who spent most of his life in Paris and London. George Bellows, the first quintessentially American artist of the 20th century, made famous in his native country painting the heaving masses of New York City and the unrestrained violence in its unlicensed boxing clubs, looked first to his European antecedents, though he never left his native shores.

In Frankie, the Organ Boy, 1907, a bright-eyed, eager-faced waif with a shock of blond hair and over-large, expressive hands emerges from the gloom in a portrait which looks directly back to Manet, while nearby, Little Girl in White (Queenie Burnett), painted by Bellows in the same year, makes unmistakable reference to Whistler’s Harmony in Grey and Green: Miss Cicely Alexander, 1872-4. But Bellows’ diffident laundry girl conveys none of the aristocratic hauteur of Whistler’s sulking young madam, while his organ boy, with a face that has something rather alarmingly fish-like about it, looks rumpled, whey-faced and undernourished.

The pulped, red-raw limbs of the two fighters appear to melt into one another on impact

Occupying the Royal Academy’s Sackler Galleries, this exhibition has been considerably pared down since travelling first from Washington’s National Gallery of Art and then New York’s Metropolitan Museum. There are 39 paintings and 37 graphic works, the latter showing off Bellows’ considerable facility as an illustrator, a career he embarked upon, just as his exact contemporary Edward Hopper had, before turning to painting. This he did under the encouragement of Robert Henri, his tutor and the founder of the Ashcan School. Henri advised his students to open their eyes to the great heaving metropolis, to its poverty and squalor. No one did this with as much gusto as Bellows, clearly the most fiercely talented of that loose association of artists.

The most well-known of his paintings are the early ones, mostly dating from the first decade of the new century, though “well-known” might be pushing it, since Bellows is little known in the UK. A tiny survey of Bellows alongside his fellow Ashcan artists was shown at the National Gallery two years ago, to an enthusiastic critical reception, but this is the first ever solo retrospective in the UK of the artist who died far too young for us to appreciate the full panorama of an admittedly uneven career.

By his mid-thirties Bellows was evidently searching for new directions, dipping his toe into 20th-century European Modernism, yet increasingly looking back to the Old Masters for stylistic approaches, with mixed results. He died at the age of 42, in 1925, of peritonitis. None of his paintings are held in a public collection outside the U.S. Yet Bellows makes us appreciate that long before the Abstract Expressionists burst onto the scene, American painting had come into its own. You really feel he deserves international reach, though it’s more than telling that for this exhibition the RA elicited no media partnership.

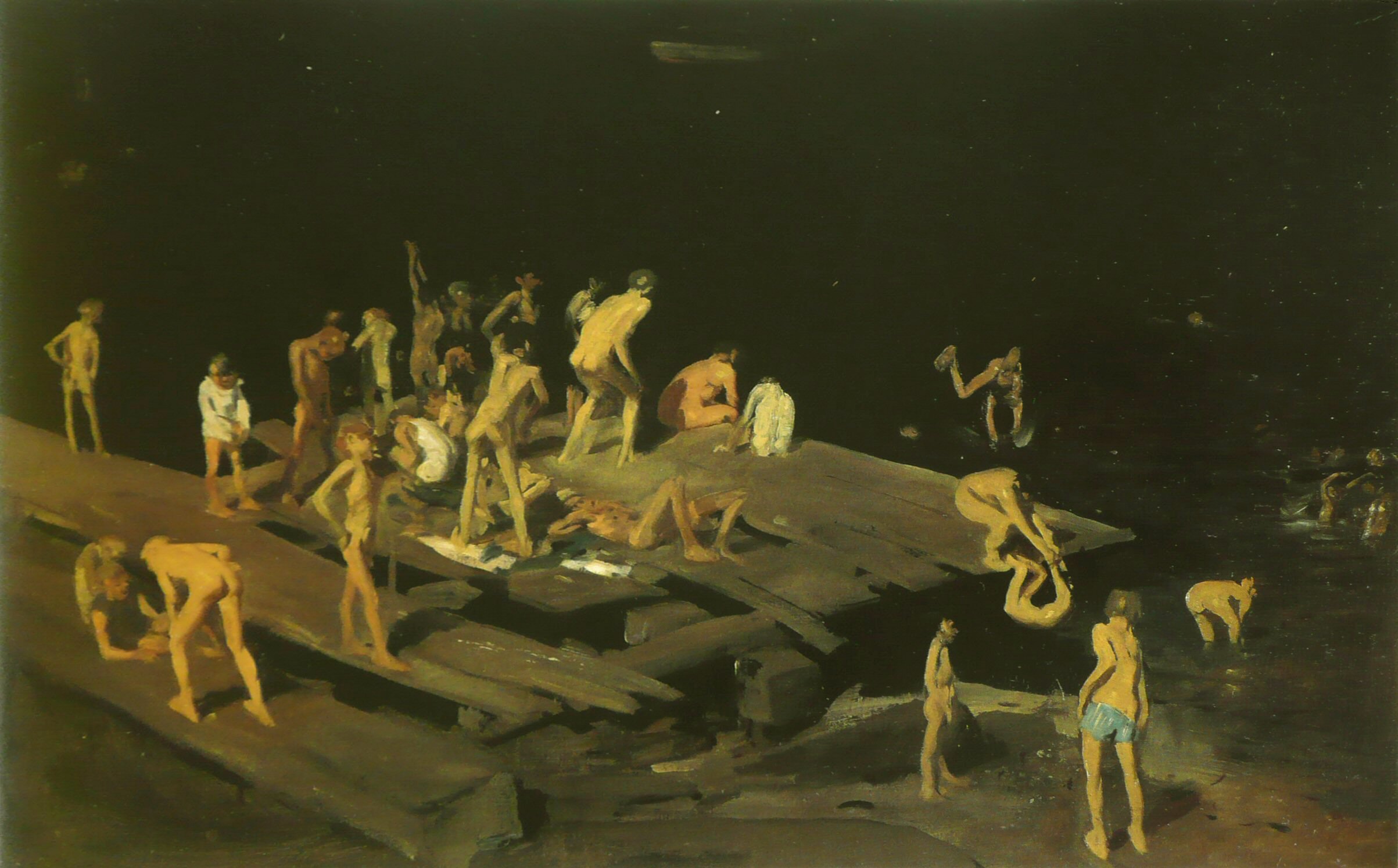

The most arresting paintings, then, are the early ones, painted when Bellows was still in his twenties. The year 1907 was a productive one, for we return to it again with Forty-Two Kids (pictured right), his exuberant painting of street urchins on the rickety pier of New York’s East River, strutting, smoking, peeing and jumping like eager seal pups into the murky water. If you think it presents a kind of sentimental, paradisiacal vision in the midst of urban squalor, then the engulfing blackness of the backdrop and the sketchiness of the figures pulls you back into uneasy ambivalence. It’s an extremely clever painting.

The most arresting paintings, then, are the early ones, painted when Bellows was still in his twenties. The year 1907 was a productive one, for we return to it again with Forty-Two Kids (pictured right), his exuberant painting of street urchins on the rickety pier of New York’s East River, strutting, smoking, peeing and jumping like eager seal pups into the murky water. If you think it presents a kind of sentimental, paradisiacal vision in the midst of urban squalor, then the engulfing blackness of the backdrop and the sketchiness of the figures pulls you back into uneasy ambivalence. It’s an extremely clever painting.

The first of his famous boxing paintings comes from this year, too: Club Night is a chiaroscuro painting of two fighters in a ring surrounded by an audience whose blurry, demonic features owes much to Goya. One of the faces abuts the picture plane, leering out at us conspiratorially from the bottom-centre foreground. Alongside it is Stag at Sharkey’s (main picture), 1909, in which the pulped, red-raw limbs of the two fighters appear to melt into one another on impact. The smears of buttery paint create a sense of uncontrolled frenzy. It’s understandably Bellows’ single most famous work.

A brilliant companion to it might have been Both Members of this Club, 1909, in which one bloodied fighter is near collapse, while his black combatant is shown both plunging into him and holding him up. Unfortunately, it’s not in the exhibition (a print of it is), but the title alludes to Bellows’ concerns regarding racial segregation, a theme that’s played out in many of his graphic works.

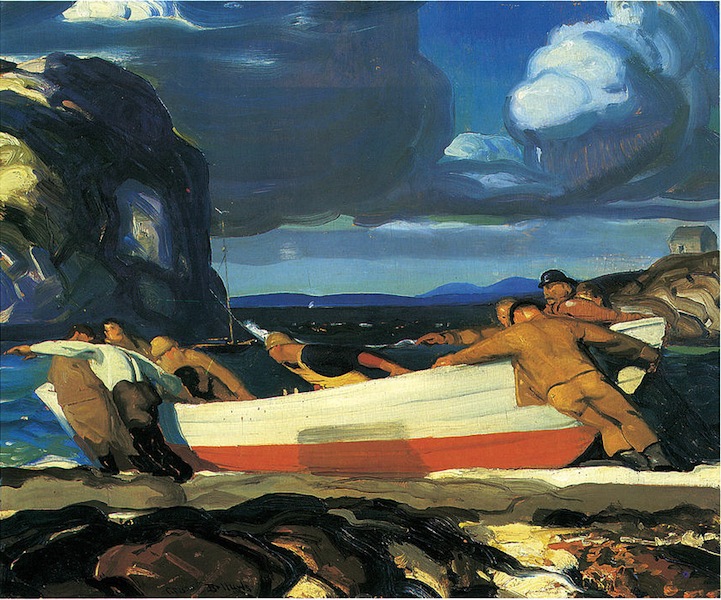

Luckily, we to have a series of paintings depicting the excavation work for Penn Station, including Excavation at Night, 1908, a work that owes much to Whistler’s smoky, fiery twilight cityscapes. Meanwhile, The Big Dory (pictured left; © New Britain Museum of American), 1913, a small but bold painting of a fishing boat being strenuously pulled and pushed by fishermen in a frieze-like line owes as much of a debt to his American predecessor Winslow Homer as to the European avant-garde in its bold strips of colour. It forms part of a strong body of work Bellows painted off the Monhegan coast in Maine.

Luckily, we to have a series of paintings depicting the excavation work for Penn Station, including Excavation at Night, 1908, a work that owes much to Whistler’s smoky, fiery twilight cityscapes. Meanwhile, The Big Dory (pictured left; © New Britain Museum of American), 1913, a small but bold painting of a fishing boat being strenuously pulled and pushed by fishermen in a frieze-like line owes as much of a debt to his American predecessor Winslow Homer as to the European avant-garde in its bold strips of colour. It forms part of a strong body of work Bellows painted off the Monhegan coast in Maine.

Thereafter we come to a group of portraits, as well as a later boxing painting set in a brightly illuminated arena, that give absolutely no sense of the energy and brio of his earlier work. We end with an uneasy mix of paintings depicting German atrocities in Belgium during the First World War, though Bellows himself never saw action and painted them only after reading war reports. I’m certainly not as dismissive of these as some critics have been, but there is an undeniable sense of a disappointing tailing off.

Clearly Bellows was struggling towards something more monumental, more durable, as in the art of the past, just as Cézanne had done. Had he lived, who knows whether he would have got there. We look to the early work to pack its considerable punch.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment