Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum, British Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum, British Museum

Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum, British Museum

An exhibition that powerfully connects you to the life of an ancient civilisation

"In the midst of life we are in death.” This is a line we may feel compelled to reverse as we encounter the first exhibits in the British Museum’s extraordinarily powerful exhibition, for this is a display vividly bringing the dead to life in the very midst of their extraordinary demise.

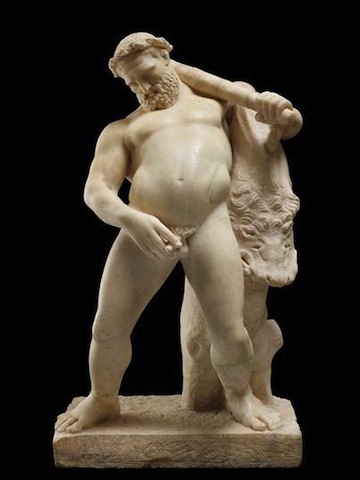

One encounter with a waving willy that lightens the mood is a statue of a drunken Hercules

The dog is the first artefact we encounter (main picture). We are witness to its pitiful last moments, its convulsions of agony frozen in perpetuity. Its collar tells us that this was a guard dog, and that it was tethered to the spot where it died. But it's not the actual body that’s preserved, for what we encounter is a perfectly formed cast. In the 1860s, Giuseppe Fiorelli, the director of excavations at Pompeii, had made body casts by injecting Plaster of Paris into the spaces left by the long-since decomposed corpses. The hardened ash had created perfect cavities through which to pour the plaster and breathe a simulacrum of life into the dead.

For centuries, both towns lay buried and largely forgotten by the world. It was only in the 18th century that excavation work began to uncover their histories, and to piece together the extent of the calamity that had befallen them. The Romans themselves had been unaware that Vesuvius posed any danger. The tremors and earthquakes that were frequently experienced by those living under its shadow were never connected to volcanic activity. An eye-witness account by Pliny the Younger gives us a first-hand encounter with the eruption, but for many centuries that account was thought to have been exaggerated for dramatic effect.

The unique conditions that created a moulding of ash to form around the dead in Pompeii ensured that wooden furnishings were completely incinerated. In Herculaneum, where the heat impact had been much greater, flesh was burned to the bone; there are only skeletal remains. However, a much higher temperature ensured that wooden objects survived remarkably intact: the stock of furniture that’s survived from Herculaneum has already been likened to a Roman Ikea, though one might argue for the higher quality of Roman craftsmanship.

The unique conditions that created a moulding of ash to form around the dead in Pompeii ensured that wooden furnishings were completely incinerated. In Herculaneum, where the heat impact had been much greater, flesh was burned to the bone; there are only skeletal remains. However, a much higher temperature ensured that wooden objects survived remarkably intact: the stock of furniture that’s survived from Herculaneum has already been likened to a Roman Ikea, though one might argue for the higher quality of Roman craftsmanship.

Still, one sees few changes in terms of the design of a table, or a baby’s cradle, which is one of the most poignant exhibits here (pictured above).

Displayed alongside the Pompeian dog, are a trestle table and a small fresco, both from Herculaneum. The carbonised table looks very similar to the one depicted in the fresco, in which an attractive young couple, both naked to the waist, pour themselves wine. Further along we find a mosaic depicting a lively dog whose collar is similar to the one worn by the dead dog. Both mosiac image and dog were found in the same dwelling.

The exhibition has been designed like the Roman villa of a wealthy family. We go from room to room, exploring the living quarters, the kitchen, the bedroom, and the beautiful frescoed garden in which birdsong plays.

Garden statuary is rather different to what we might expect in a more modern household. Romans had a rather relaxed attitude to sex and tumescent cocks are everywhere to be spied. In their humour, these Roman citizens were happy to display body parts that other civilisations have regarded as distinctly private. (Here I’ll bring up just one note of irritation: the labels that emphatically insist that these displays are humorous but not sexual seem somewhat unconvincing; humour, sex and titillation have been perfect bed fellows since time immemorial, even, one suspects, among the Romans, and this determination to separate what's funny from what might also be perceived as erotic or titillating seems odd).

One encounter with a waving willy that lightens the mood is a small marble statue of a drunken Hercules (pictured left), the demi-god who gave his name to Herculaneum. He has obviously enjoyed a long night out with Bacchus and is now taking a well-deserved pee. Meanwhile, a tavern painting uses the humour of a cartoon storyboard to remind customers to behave.

One encounter with a waving willy that lightens the mood is a small marble statue of a drunken Hercules (pictured left), the demi-god who gave his name to Herculaneum. He has obviously enjoyed a long night out with Bacchus and is now taking a well-deserved pee. Meanwhile, a tavern painting uses the humour of a cartoon storyboard to remind customers to behave.

The funny and the disarmingly moving are interweaved, but little prepares you for the emotional impact of the last gallery. In this stark, narrow room, empty except for human casts, we find the so-called "resin woman", lying prostrate with her face frozen in a rictus of agony or terror; and finally the family of four: the mother with her child in her lap, her arms raised in the attitude of a boxer due to the tightening of tendons in extreme heat, while her child rears up, perhaps to claw at the wall that’s no longer there to his right. Overcome by searing heat, the father rears back, while another child lies slightly separated from the three.

It’s a desperately affecting, haunting sight. But what stays with you, in fact, is the sense of a living community, the sensation of vibrant life, and how much we feel connected to these people in their ordinary humanity.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Comments

The interpretation of the