Ellen Gallagher: AxME, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Ellen Gallagher: AxME, Tate Modern

Ellen Gallagher: AxME, Tate Modern

She may be obsessed with a single issue but the humour, beauty and variety of the work makes for a rich experience

Ellen Gallagher is obsessed by the issue of black cultural identity; but if that sounds tedious or tendentious, think again. She explores her theme in work that is so varied, so beautiful and so humorous that the furrow she ploughs seems more like an endless opportunity than a narrow limitation.

Take the early paintings, for instance. From a distance they look like exquisite minimalist compositions – explorations in pure abstraction. Gallagher paints onto sheets of penmanship paper used by American schoolchildren when practising their handwriting. This underlying grid is enhanced by the thin blue lines printed on the paper to help wayward pupils control their erratic scribblings. These remind one of Agnes Martin’s abstract forays into the articulation of space, yet one can’t help reading the insistent structure metaphorically – as indicative of a set of conventions designed to encourage conformity.

Hovering over the lines is a mesmerising haze of dots and rings resembling frog spawn. In Oh! Susanna (1993) the rings are joined by sausage shapes; every now and then, the elements coalesce into a comic face comprised of goggle eyes and a grinning mouth – shorthand for the “black face” make-up used in black and white minstrel shows to transform white faces into caricatures of black ones.

Hovering over the lines is a mesmerising haze of dots and rings resembling frog spawn. In Oh! Susanna (1993) the rings are joined by sausage shapes; every now and then, the elements coalesce into a comic face comprised of goggle eyes and a grinning mouth – shorthand for the “black face” make-up used in black and white minstrel shows to transform white faces into caricatures of black ones.

Introducing low-brow figuration into the rarefied realm of abstraction is like letting off a stink bomb in a perfume factory. And the result is as subversive as it is funny – tantamount to thumbing one’s nose at the refined sensibilities of both Agnes Martin and Sol LeWitt. As if slipping a political message into a minimalist painting is not bad enough, Gallagher also brings slapstick into the erudite conversation in the form of white faces that lasciviously stick out their tongues among the cartoon eyes and leering mouths. From a distance decorum may appear to be maintained, but Pinocchio Theory doesn’t even pretend to be high-brow. A long strip of black wood is adorned with eyes and lips painted to create a chorus line of minstrel faces, apparently stretching to infinity in an abusive parody of black features. Gallagher refers to the faces as the "disembodied ephemera of minstrelsy".

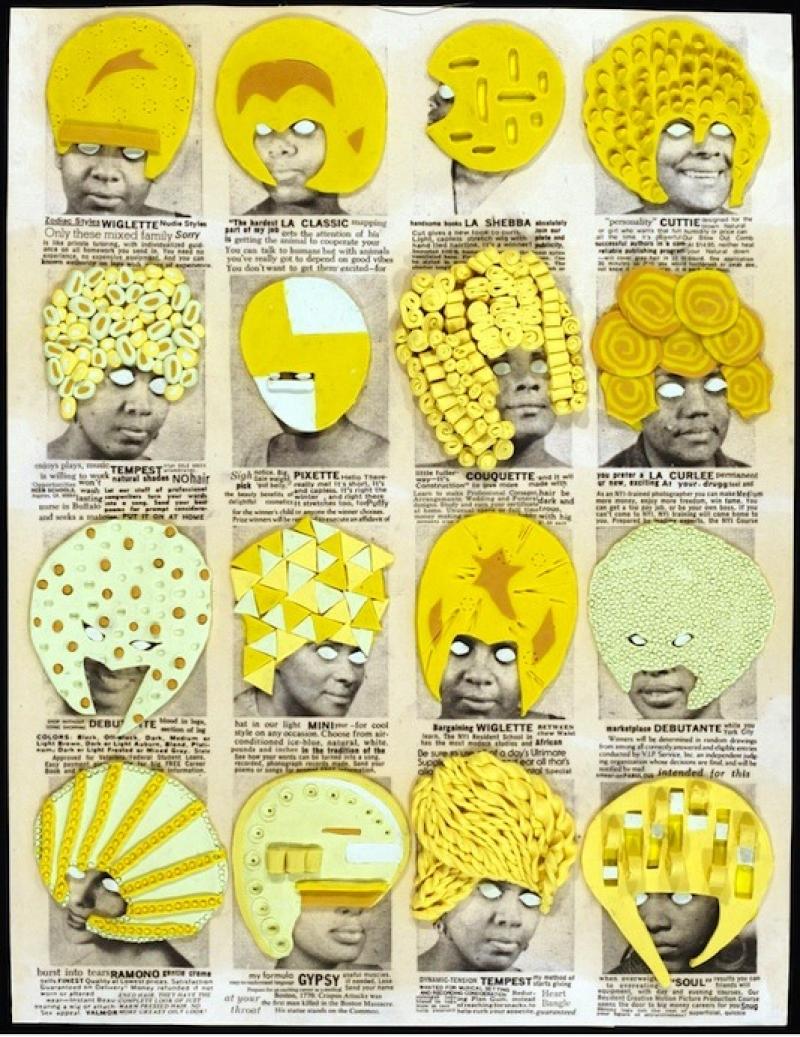

The grids structuring works like Double Natural, Pomp- Bang and Deluxe (2004) (pictured above right: So Fun from Deluxe) were inspired by the small ads appearing in magazines such as Ebony, Sepia and Our World to sell wigs and skin-lightening products to African Americans. Extravagant hair pieces resembling helmets, swimming caps, visors, baskets and even cakes are given names like Lioness, Tempest and Gypsy to suggest a wild and passionate nature. Using yellow plasticine, Gallagher transforms the wigs into monstrous constructions resembling instruments of torture and by removing their eyes, she reduces the models to robotic cyphers whose desire to resemble blonde caucasians robs them of their identity.

If the Yellow Paintings emphasise the corrosive ability of advertising to undermine someone’s self-esteem, in Monster, a sci-fi film made with Dutch artist Edgar Celine, Gallagher goes even further. Fiery blonde wigs are used to indicate alien abduction; they control the actions of the wearer, reducing him or her to an instrument of alien intelligence.

If the Yellow Paintings emphasise the corrosive ability of advertising to undermine someone’s self-esteem, in Monster, a sci-fi film made with Dutch artist Edgar Celine, Gallagher goes even further. Fiery blonde wigs are used to indicate alien abduction; they control the actions of the wearer, reducing him or her to an instrument of alien intelligence.

In the Black Paintings the artist hides her subjects beneath a layer of black enamel paint. You have to look from an angle to see dancing figures resembling Javanese puppets buried in the low relief, or a man with his hair shaved into a mohican and his neck and scalp covered in tattoos or curling hair. These denizens of darkness offer a tantalising glimpse of the subcultures that thrive beneath the radar of the white-dominated mainstream.

Curlicues, fingers and tendrils of hair begin to insinuate themselves more and more as subversive elements that cloud the view, engulf the scene or morph into undesirable forms. For instance, they creep over the bars of Preserve (2001), a white structure resembling a climbing frame or a Sol LeWitt sculpture, to evoke the ivory or bone carvings often made by sailors on whaling ships. Melville’s Moby Dick has long been a source of inspiration and the peg-legged figure in Bird in Hand (2006) (pictured) is partly based on the irrascible Captain Ahab. And half way through the exhibition, the emphasis shifts from land to sea.

As a student, Gallagher studied oceanography and spent a semester on a research ship studying pteropods, wing-footed snails. Exquisite watercolours and paper cutouts record in minute detail the appearance of subaquatic creatures such as sea worms, puffer fish and octopuses. In Watery Ecstatic, a series of drawings begun in 2001, her fascination with both exotic marine life and exaggerated hairdos combine into an underwater extravaganza. Those ubiquitous eyes, for instance, become bubbles rising from a whale carcass before morphing into heads sporting preposterous wigs, whose extended locks waft in the current like seaweed. Other heads are trapped in strands of green seaweed that emanate from a giant creature resembling a cross between an octopus and a jelly fish that has fleshy, magenta coloured tentacles (pictured below).

In the film installation Murmur (2003-4), a shoal of black fish in blonde wigs swims around with synchronised perfection, completely in harmony with the underwater world. And in the drawings, the women seem similarly released from bondage, since their headgear is no more extravagant than the scales, fins and tentacles of the sea creatures with whom they share the watery depths.

In the film installation Murmur (2003-4), a shoal of black fish in blonde wigs swims around with synchronised perfection, completely in harmony with the underwater world. And in the drawings, the women seem similarly released from bondage, since their headgear is no more extravagant than the scales, fins and tentacles of the sea creatures with whom they share the watery depths.

The relationship between the two worlds – of marine life and terrestrial politics – comes solely from Gallagher’s experience of them both, but in Watery Ecstatic she creates a convincing picture of a mermaid-like idyll in which freedom from marginalisation is possible, since all forms of life seem so alien and exotic that nothing can be deemed out of place. It's a fantasy, of course, but the drawings are so beautiful that one needs little encouragement to indulge the dream.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment