Early on in Dangerous Edge: A Life of Graham Greene, John le Carré remembers Greene telling him that childhood provides “the bank balance of the writer”. Greene remained in credit on that inspiration front throughout his life, even while he struggled financially in his early writing days with a young family; later in life, too, he lost everything to a swindling financial adviser – the move to France was to avoid the Revenue.

Greene went to Berkhamstead School, where his father was headmaster, and was bullied, not least for the assumption that he was a spy for paternal authority (the spy persona would return later in reality; psychologically he himself remained “his most elusive character”). He experienced profound depression – those brushes with suicide through Russian roulette – and at the age of 16 underwent six months of psychoanalysis, an experience certainly progressive for its time. One of his therapist’s recommendations was that Greene pursue writing.

Travel and the act of writing itself his were ways of dealing with that depression

It wasn’t termed bipolar depression then, but director Thomas P O’Connor’s film, the first American-produced study of the writer, originally made for PBS, treats Greene’s life and work through that prism. Travel and the act of writing itself were ways of dealing with that depression (Greene frequently used the word “boredom” to convey the sense of his “disturbance with the universe”), which also left him ill-suited to domesticity.

His long-suffering wife Vivien knew that better than anyone – he had told her that he had “a character profoundly antagonistic to ordinary domestic life”, but that “unfortunately, the disease is also one’s material.” That meant that he was unfaithful to her, and their Catholicism prevented a separation. The closest of his later relationships, from which came The End of the Affair, was arguably that with Catherine Walston, who was as complicated (and promiscuous, we hear here) as he was (the situation had been pre-visited in The Heart of the Matter, whose hero, Scobie, stays true to his final appointment with the revolver).

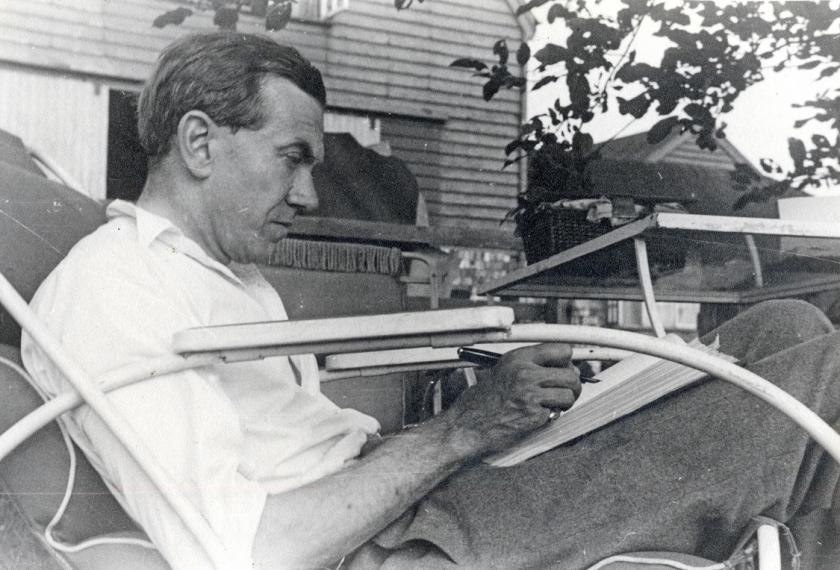

Dangerous Edge excels in its use of archive, on two fronts particularly - the travels, and Greene’s (and his novels’) connections with cinema. That restlessness – little surprise he titled his memoir Ways of Escape – and those commissioned journeys that answered an addiction to danger would bring forth both the travel books, and the physical and psychological landscapes of so many of the great novels. On the personal front Africa was as important a destination as any: on his very first trip outside Europe, to Liberia in 1935 for A Journey Without Maps, he nearly died of sickness and discovered a “passionate interest in living”; at a spiritual low point in the late Fifties, he would return to the leper colonies of the Congo, and recover himself (A Burnt-Out Case, a self-portrait with more adultery).

Dangerous Edge excels in its use of archive, on two fronts particularly - the travels, and Greene’s (and his novels’) connections with cinema. That restlessness – little surprise he titled his memoir Ways of Escape – and those commissioned journeys that answered an addiction to danger would bring forth both the travel books, and the physical and psychological landscapes of so many of the great novels. On the personal front Africa was as important a destination as any: on his very first trip outside Europe, to Liberia in 1935 for A Journey Without Maps, he nearly died of sickness and discovered a “passionate interest in living”; at a spiritual low point in the late Fifties, he would return to the leper colonies of the Congo, and recover himself (A Burnt-Out Case, a self-portrait with more adultery).

Greene must be one of the most filmed authors of his century, and that's no less comprehensively illustrated here. Like his division of his literary output into novels and “entertainments”, the latter designed as much as anything to pay the bills, films were even more lucrative when they worked out, and talked down by Greene in the same way (“I’m trusting the shocker to pay,” he wrote to his brother of his 1936 novel A Gun for Sale, later filmed as This Gun for Hire, poster above left). But the connection was far greater, as Greene himself would admit: “When I describe a scene… I capture it with the moving eye of the cine-camera rather than with the photographer’s eye.”

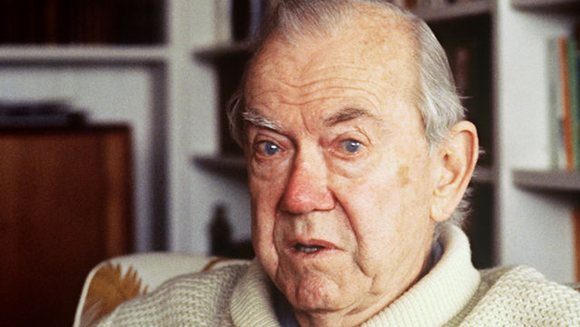

Dangerous Edge gives more attention to pictures than to people. Running to a compact hour, its virtue as an overview is considerable, making for a briskness that is bound to strike when set against the three-part Arena film from the early 1990s. Greene himself features in a couple of earlier screen interviews (in one he relates how "Papa Doc" Duvalier reacted to his depiction of Haiti in The Comedians), but it’s his voice (extracts from the works are read with great character by Bill Nighy) that guides us, and we hear Vivien too. Derek Jacobi narrates, and the assembled talking heads certainly give a sense of Greene’s personality (Greene in later life, below right). There’s bite-sized critical commentary from David Lodge, even if we wonder how much the frame of some of that explication (“the novel begins…”) is aimed at Greene novices.

The shortcoming of such an approach to "talking heads” is how it limits the potential expansion of perspective to half-portrait or even (perish the thought!) portrait-in-landscape, and excludes the more garrulous complexity that, some would say, is life’s true fabric. It’s an approach to documentary-making, arguably more American in character, that puts fact first. Paradoxically Greene might have approved – his own prose was always informational, pragmatic even. And he wrote: “If one knew, he wondered, the facts, would one have to feel pity even for the planets?” Yet that’s surely as ambiguous a sentence as ever came from his pen.

The shortcoming of such an approach to "talking heads” is how it limits the potential expansion of perspective to half-portrait or even (perish the thought!) portrait-in-landscape, and excludes the more garrulous complexity that, some would say, is life’s true fabric. It’s an approach to documentary-making, arguably more American in character, that puts fact first. Paradoxically Greene might have approved – his own prose was always informational, pragmatic even. And he wrote: “If one knew, he wondered, the facts, would one have to feel pity even for the planets?” Yet that’s surely as ambiguous a sentence as ever came from his pen.

Add comment