To Kill A Mockingbird, Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

To Kill A Mockingbird, Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre

To Kill A Mockingbird, Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre

London ain't Alabama, but Harper Lee's attack on racial intolerance still resonates

Every May the townspeople of Monroeville, Alabama, the home of Harper Lee, perform Christopher Sergel’s theatrical adaptation of Lee’s acclaimed, much beloved novel, on the grounds of the county courthouse. It’s a potent, somehow ironic demonstration of the enduring regard for the novel, in the very part of America whose racial intolerance Lee exposed.

It’s one thing performing, and seeing this story of the Deep South in its steamy locale, where even the shade is “sweltering” and “men’s stiff collars wilted by nine in the morning”, another outdoors in a still painfully chilly London May. But it’s testament to Timothy Sheader’s production that for long moments we are agreeably wrapped in the story’s magical embrace.

The play starts with a surprise. First one actress steps up in the midst of the audience and starts reading, literally, from a copy of the book. We assume this will be the narrator; but then another takes over, then an actor, and before we know it the six-year-old Jean Louise Finch, aka Scout, is multi-form amongst us.

The play starts with a surprise. First one actress steps up in the midst of the audience and starts reading, literally, from a copy of the book. We assume this will be the narrator; but then another takes over, then an actor, and before we know it the six-year-old Jean Louise Finch, aka Scout, is multi-form amongst us.

While Sergel sensibly retained Scout’s distinctive voice by utilising an on-stage narrator, Sheader’s masterstroke is to share the task around his cast, all but four (the lead, and the children) dropping away from their characters to pick up a text and read to the audience. The move is not only theatrically dynamic, but somehow underlines the sense of ownership that anyone who has read the book feels for it.

The breathless excitement of the opening continues as the actors head for the stage – bare except for a tree – and start describing in chalk the Finch home and its immediate environs in the fictional town of Maycomb. Musician Phil King, who will regularly emerge with his guitar and harmonica, breaks into a song. And 1930s Alabama, bar the heat, is in place.

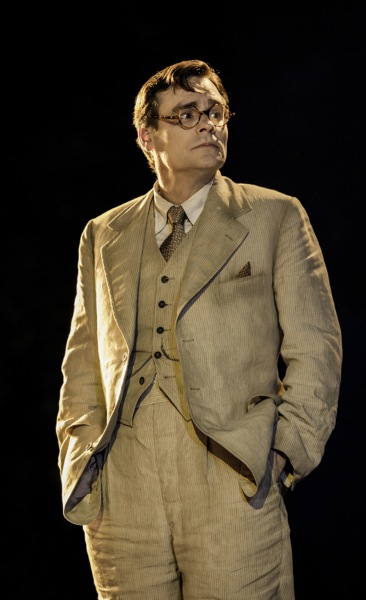

We are speedily, efficiently introduced to the chief characters. The tale centres on the Finches – Scout and her older brother Jem, their middle-aged, widowed father Atticus (Robert Sean Leonard, pictured above right) their black housekeeper Calpurnia and their friend Dill. The children’s mix of fascination and fear for the recluse Boo Radley informs many of their summer pranks; meanwhile Atticus prepares for the defence of Tom Robinson (Richie Campbell, pictured below), a black worker who has been falsely accused of rape yet whose guilty verdict is a foregone conclusion.

If at times we miss a true sense of locale (the accents seem middling amongst the adults, are understandably casual in the children), Lee’s themes are powerfully felt: the corrosive depiction of racism offset by her call for tolerance and empathy, the children’s treatment and changing perception of Boo Radley reflecting the bigger challenges faced by their father. It’s also perhaps the most affecting account of good parenting ever written. The scene here in which Atticus faces the angry mob intent on lynching Tom is appropriately chilling, his overwhelmed reaction to his children’s support in that moment – which effectively saves his life – and the moral he imparts as a result incredibly moving.

If at times we miss a true sense of locale (the accents seem middling amongst the adults, are understandably casual in the children), Lee’s themes are powerfully felt: the corrosive depiction of racism offset by her call for tolerance and empathy, the children’s treatment and changing perception of Boo Radley reflecting the bigger challenges faced by their father. It’s also perhaps the most affecting account of good parenting ever written. The scene here in which Atticus faces the angry mob intent on lynching Tom is appropriately chilling, his overwhelmed reaction to his children’s support in that moment – which effectively saves his life – and the moral he imparts as a result incredibly moving.

Much rests on the children. Making her professional debut, Izzy Lee captures Scout’s scamp-like quality (though perhaps overdoes the wistfulness), Adam Scotland Jem’s charming intention to grow up fast, Harry Bennett Dill’s desperate desire for a family. They’re an engaging bunch. But I was a little less convinced by the star in town – and the only American in the cast – Robert Sean Leonard.

While it would be unjust to evoke Gregory Peck’s performance in the flawless film adaptation, this does fall short of what I regard as Leonard’s potential for the role. The actor captures the character’s moral fibre, his paternal fondness, but somehow misses the inner strength. His courtroom summation is faltering, the bowed gait and melancholy air at times underwhelming.

The ensemble is very effective, but special mention has to go to Simon Gregor’s villain of the piece, Bob Ewell, and Richie Campbell’s Robinson, whose courtroom speech captures the desperation of a man whose only crime is to feel sorry for a white girl.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Add comment