Alternative Guide to the Universe, Hayward Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Alternative Guide to the Universe, Hayward Gallery

Alternative Guide to the Universe, Hayward Gallery

Visionaries, eccentrics and misfits share their visions of the future

The Alternative Guide to the Universe, an exhibition of work mainly by self-taught practitioners, encourages one to speculate on the merits of orthodox art and science compared with the wild schemes pursued by these eccentrics and visionaries, some of whom are inspirational while others bludgeon you with their offbeat ideas.

Bodys Isek Kingelez builds immaculate models of imaginary buildings that make Dubai’s waterfront hotels look positively boring. Resembling a rhino horn, Dorothe, 2007 (pictured below right, courtesy André Magnin, Paris) arcs into the sky, one facade zigzagged by gleaming red spangles, the other patterned with fine line drawings. Angled at 45 degrees, Bodystand soars like a rocket above the swimming pool nestling timidly at its base. As well as these leaning towers, there’s a flamboyant airport, a sports stadium made from beer and coke cans and a new HQ for the UN decorated with colourful frills, grids and stars that would surely spread optimism among the delegates.

Kingelez lives in Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo; despite having no training as an architect and little hope of turning his cardboard maquettes into actual buildings, he believes that his Architectural Modelism can contribute "to creating a new world". He has never travelled abroad and claims not to look at magazines. "For me," he says, "Kinshasa was The City. I had never seen any other, not even in photos." So how is it that his schemes, which appear to him as full-blown visions, seem to embrace Art Deco and Post-Modernism as well as Sant’Elia’s futuristic fantasies? And if he had trained as an architect would it have killed his astounding creativity or enabled it to blossom? Questions like these continually surface as you go round this fascinating show.

Kingelez lives in Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo; despite having no training as an architect and little hope of turning his cardboard maquettes into actual buildings, he believes that his Architectural Modelism can contribute "to creating a new world". He has never travelled abroad and claims not to look at magazines. "For me," he says, "Kinshasa was The City. I had never seen any other, not even in photos." So how is it that his schemes, which appear to him as full-blown visions, seem to embrace Art Deco and Post-Modernism as well as Sant’Elia’s futuristic fantasies? And if he had trained as an architect would it have killed his astounding creativity or enabled it to blossom? Questions like these continually surface as you go round this fascinating show.

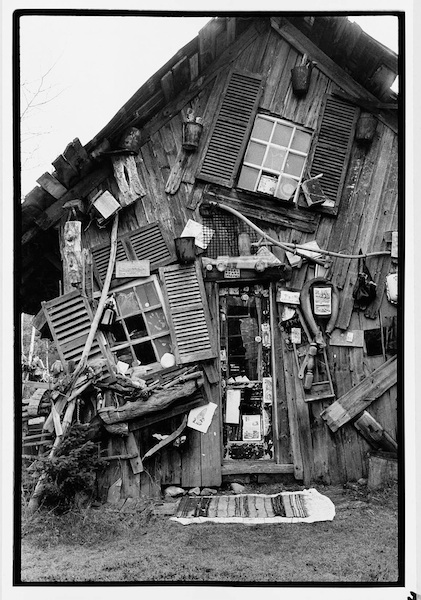

At the other extreme from Kingelez’s grand visions of urban utopias are the ramshackle structures built by Richard Greaves around his home in the Beauce forest in Quebec (pictured below left, Sugar Shack, 2001, photographed by Mario del Curto). Constructed from wood gathered from abandoned barns and held together with baling twine, the shacks appear on the verge of collapse yet are remarkably stable. A bike perches on the roof of The Three Little Pigs’ House, a three-part assemblage of old windows, doors, planks and branches that affords a superb adventure playground for children who squeeze through narrow spaces devoid of right angles, climb vertiginous stairs or shin up ropes to higher and more precarious levels. Like tree houses that have dropped to the ground but survived the impact, the sheds seem to thumb their noses at the principle of entropy. Instead of crumbling into dust, these heaps of junk defy decay to become wonky emblems of resilience.

The exhibition contains numerous architectural visionaries such as Marcel Storr, an illiterate Paris road-sweeper who spent his spare time painting jewel-like pictures of soaring cathedrals (pictured below right, courtesy of Liliane and Bertrand Kempf) whose multiple spires resemble the tiered ziggurats of the Temple of Angkor Wat. He imagined Paris being destroyed in a nuclear holocaust after which he would be called upon to rebuild the city. In 1974 he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital where he was described as “a megolomaniac who appears to be a great painter”.

The exhibition contains numerous architectural visionaries such as Marcel Storr, an illiterate Paris road-sweeper who spent his spare time painting jewel-like pictures of soaring cathedrals (pictured below right, courtesy of Liliane and Bertrand Kempf) whose multiple spires resemble the tiered ziggurats of the Temple of Angkor Wat. He imagined Paris being destroyed in a nuclear holocaust after which he would be called upon to rebuild the city. In 1974 he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital where he was described as “a megolomaniac who appears to be a great painter”.

The sanity of A.G Rizzoli is also open to doubt. While working as an architectural draughtsman, he lived with his mother in San Francisco. His first glimpse of female genitalia, at the age of 40, caused him acute anxiety which he sought to alleviate by designing “a piece of architecture radically different” – a phallic tower flanked by symmetrical wings. In many of his drawings people are represented as neoclassical buildings, his beloved mother being visualised as an ornate cathedral. His most compelling design is Yield to Total Elation, a utopian city supposedly inspired by saints, spirit guides and his heavenly assistant, John F. Kennedy. Resembling the ground plan of a cathedral, the scheme includes a Sitting Station (public lavatory), a Temple of Dreams and a Shrine of Ascension – for euthanasia, “a pleasant, painless bon voyage from this land”.

Having been orphaned at the age of eight, the adult Morton Bartlett lived alone in Boston and worked as a graphic designer and photographer. He peopled his solitude with lifelike plaster sculptures of children (pictured below left. Untiitled, 1950s) – mainly girls aged eight and upwards – which he dressed, posed and photographed in shots that have the uncanny eroticism of Balthus’ paintings of young girls. Creepily intimate, they make one wonder about his imagined relationship with these often naked children.

Having been orphaned at the age of eight, the adult Morton Bartlett lived alone in Boston and worked as a graphic designer and photographer. He peopled his solitude with lifelike plaster sculptures of children (pictured below left. Untiitled, 1950s) – mainly girls aged eight and upwards – which he dressed, posed and photographed in shots that have the uncanny eroticism of Balthus’ paintings of young girls. Creepily intimate, they make one wonder about his imagined relationship with these often naked children.

When arthritis forced her to retire from her job as a chemical analyst in Xi’an in China, Guo Fengyi began practising qigong to alleviate the pain. In 1989 she started making large drawings of the visions she saw while meditating, which she said “come from the sky” and map energy fields in the body. One image is distinctly vaginal while a large scroll, painted in sections so the whole was visible only on completion, depicts a phallic shaft of energy culminating in an explosion of billowing red pulses.

Other delights include an airborne fleet of skate boards freighted with letter forms (main picture). They were constructed from plastic toys, costume jewellery and assorted junk by New York graffiti and hip hop artist, Rammellzee as an assault on the restrictions placed on language by orthodox spelling and grammar.

At its best, art opens the mind by offering fresh perspectives on life, and some of these misfits and dropouts provide valuable glimpses of the unknown or unfamiliar. But the presence of numerous techno geeks and sci-fi freaks hell-bent on explaining obscure theories makes one feel trapped in a dark corner, unable to escape. Paul Laffoley from Boston, Massachusetts is one such obsessive, convinced that he has seen the light. In heavily annotated paintings, he reveals the vital information given him by the alien Quazgaa Klaatu who visited him as a body of light. The Atlantean Time Machine, 1976, for instance, is a device that "engineers the consciousness of the operator, which then can move backwards or forwards in time and allows for the out of body experience that leads to the bio-location in space time that is the definition of time travel".

At its best, art opens the mind by offering fresh perspectives on life, and some of these misfits and dropouts provide valuable glimpses of the unknown or unfamiliar. But the presence of numerous techno geeks and sci-fi freaks hell-bent on explaining obscure theories makes one feel trapped in a dark corner, unable to escape. Paul Laffoley from Boston, Massachusetts is one such obsessive, convinced that he has seen the light. In heavily annotated paintings, he reveals the vital information given him by the alien Quazgaa Klaatu who visited him as a body of light. The Atlantean Time Machine, 1976, for instance, is a device that "engineers the consciousness of the operator, which then can move backwards or forwards in time and allows for the out of body experience that leads to the bio-location in space time that is the definition of time travel".

In detailed diagrams fellow Americans James Carter and Philip Blackmarr illustrate their alternative theories of physics and Ionel Talpazan, who lives in New York and claims to have “sacrificed his life to the UFO”, shares some of the 1,000 or so images he has made of these alien craft. Like many of the others, he believes his theories will help create a better world – if only someone will listen.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment