Collecting Gauguin, Courtauld Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Collecting Gauguin, Courtauld Gallery

Collecting Gauguin, Courtauld Gallery

Samuel Courtauld's staggering collection of Gauguins is second only to his Cézannes

A one-room display at the Courtauld of seven paintings, a wall of woodcuts, some drawings and a sculpture by the passionate and volatile Gauguin: for all its modesty, this is a staggeringly powerful show, replete with exotic dreams and embodying the power of the artist’s lasting influence.

Exotic landscapes and primitive interiors are infiltrated by scenes of languorous naked women, the colour of milk chocolate, cross-legged on the floor, stretched on a couch, bathing in a pool, awkward odalisques, impassive goddesses or acquiescent mistresses. Gauguin was one of the ultimate escape artists, sacrificing remuneration (and his Danish wife and family) for the cause of art, and eventually even leaving Paris behind for the Caribbean and the South Seas. He protested against colonialism while subscribing to some romantic notions of the supposed honesty of “primitive” societies and succumbing to hard drinking and syphilis. He wrote to Strindberg that it was civilisation that made him suffer, that barbarism was rejuvenation. In the Marquesas Islands, he wrote, there is poetry, “and all you have to do to suggest it in painting is to surrender oneself to dreams”.

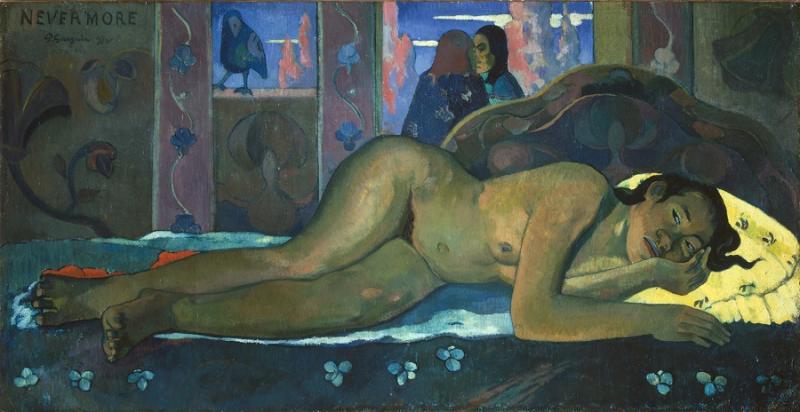

And dreams there are: while his most famous and largest allegorical painting, the perfectly titled Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where are We Going? is in Boston, the Courtauld has the hypnotic Nevermore painted in Tahiti, its apprehensive, uneasy reclining woman surrounded by patterned cloths, two mysterious visitors who seem to be in intense discussion, all overseen by a crow, with a vast landscape surmounted by streaks of cloud just glimpsed through the windows. Te Rerioa (The Dream) (pictured above right) has more island landscape, a background for a highly decorated interior with symbolic murals on the walls, the whole a setting for two women, a cat and a baby, in enigmatic relationships.

And dreams there are: while his most famous and largest allegorical painting, the perfectly titled Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where are We Going? is in Boston, the Courtauld has the hypnotic Nevermore painted in Tahiti, its apprehensive, uneasy reclining woman surrounded by patterned cloths, two mysterious visitors who seem to be in intense discussion, all overseen by a crow, with a vast landscape surmounted by streaks of cloud just glimpsed through the windows. Te Rerioa (The Dream) (pictured above right) has more island landscape, a background for a highly decorated interior with symbolic murals on the walls, the whole a setting for two women, a cat and a baby, in enigmatic relationships.

Gauguin courageously attempted to address the weightiest of questions and themes. Nearly two decades after his death his son Pola oversaw the production of a magnificent series of wood engravings called Noa, Noa on a variety of spiritual themes, from an evocation of the spirits of the dead to the simple matter of the creation of the universe. The one unexpected oddity is the neo-classical signed portrait in marble of his young and beautiful wife Mette (pictured below); the assumption is that Gauguin modelled it, but that a master carved it. Either way, it is one of only two marbles he created.

The Courtauld owns the most significant and largest collection of Gauguin in Britain; its five paintings are joined by two – a landscape of Martinique and Bathers at Tahiti. (The Cézanne collection, also the largest in Britain, is simply staggering.) Courtauld was purchasing for a decade from 1922 at a time when the Tate was busily turning down masterpiece after masterpiece, and only a few connoisseurs and critics were promoting avant-garde art from across the Channel. His photograph – an impeccably besuited plutocrat, formidably well groomed – presides over this current show. His individual taste has been our luck.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment