theartsdesk in Saint Louis, Missouri: A Boxing Opera | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Saint Louis, Missouri: A Boxing Opera

theartsdesk in Saint Louis, Missouri: A Boxing Opera

A jazz opera enters the ring to portray the fight game

The Opera Theatre of Saint Louis has been sometimes dubbed the "Glyndebourne of America" due to the charming garden picnics enjoyed by patrons during the sizzling Missouri summer season. But that title also suggests the company's daring international programming. Since 1976 Opera Theatre has hosted 22 world premieres and 23 American premieres, almost certainly the highest percentage of new work of any American company.

Champion is the first of a three-year cycle of operas specifically dealing with “new American realities” and deliberately aimed to lure a broader, more diverse audience, meaning not just white and ideally under 60, an ambitious scheme in a city where racial division is still socially evident.

'I killed a man and the world forgives me / I love a man and the world wants to kill me'

Champion also has the honour of being perhaps the world's first full-length boxing opera, the only other close contenders being Shadowboxer, about Joe Louis, and a short work, Approaching Ali, recently mounted by Washington National Opera. Not to be confused with the gimmickry of "Chessboxing", the notion of "Opera Boxing" actually makes perfect sense. All the passion and physicality of the ring ensures steamy melodrama worthy of the grandest 19th-century operatic themes, while two highly artificial forms find their ultimate authenticity precisely within the regulations of their traditions. After all, both boxing and opera are known for their African-American celebrities, Blanchard's own father being a practising baritone.

And Champion is certainly rich in drama, revealing the extraordinary true tale of welterweight champion Emile Griffith, an immigrant from St Thomas in the Virgin Islands who was diverted from his original career as, yes, a hat designer to become instead a highly successful fighter. Then in 1962 Griffith found himself matched against Benny "Kid" Paret who made a point of dissing him as a “maricon”, Spanish slang for a homosexual, and inspiring Griffith to land some 17 blows in just seven seconds knocking Paret into a deep coma from which he never recovered. Griffith was haunted for the rest of his life by guilt at having killed his opponent, while also being equally disturbed by the very homosexuality with which he'd been taunted. Indeed, in a resonant irony, Griffith himself was later beaten unconscious by gay-bashers on leaving one of his nocturnal haunts.

The full poignancy of this story is ably captured in the libretto by playwright-screenwriter Michael Cristofer (Witches of Eastwick, Bonfire of the Vanities). It begins with Griffith as an old man with memory loss trying to recall his youth and eventually essaying some reconciliation with his past through a meeting with the son of the man he slayed. The libretto delights in agile rhyme - “How does it feel/ Emile”, “in this corner/ in a coma” - and in a sort of poetically tweaked vernacular: “I killed a man and the world forgives me/ I love a man and the world wants to kill me.” The strength of the text is made clear thanks to surtitles, though St Louis is still sufficiently conservative that they simply leave out all the racier language, whether it's the word “ass” or a splendid aria commencing “well fuck me sideways.”

The full poignancy of this story is ably captured in the libretto by playwright-screenwriter Michael Cristofer (Witches of Eastwick, Bonfire of the Vanities). It begins with Griffith as an old man with memory loss trying to recall his youth and eventually essaying some reconciliation with his past through a meeting with the son of the man he slayed. The libretto delights in agile rhyme - “How does it feel/ Emile”, “in this corner/ in a coma” - and in a sort of poetically tweaked vernacular: “I killed a man and the world forgives me/ I love a man and the world wants to kill me.” The strength of the text is made clear thanks to surtitles, though St Louis is still sufficiently conservative that they simply leave out all the racier language, whether it's the word “ass” or a splendid aria commencing “well fuck me sideways.”

In fact, despite the potentially controversial subject matter - racism, homosexuality, prostitution - there is a certain curious conservatism to the final work, most especially Blanchard's score which is pleasingly lyrical, rich in its mounting elegiac lilt, finely modulated, yet ultimately perhaps too self-consciously crafted if not cautious. A beautiful song such as "This Night Is Long", as delivered with exceptional grace by Jordan Jones as the young Emile, and the resonant reprise "What Makes a Man a Man?" might be worthy of the great American songbook, but the overall effect is closer to, say, Gian Carlo Menotti than Porgy and Bess.

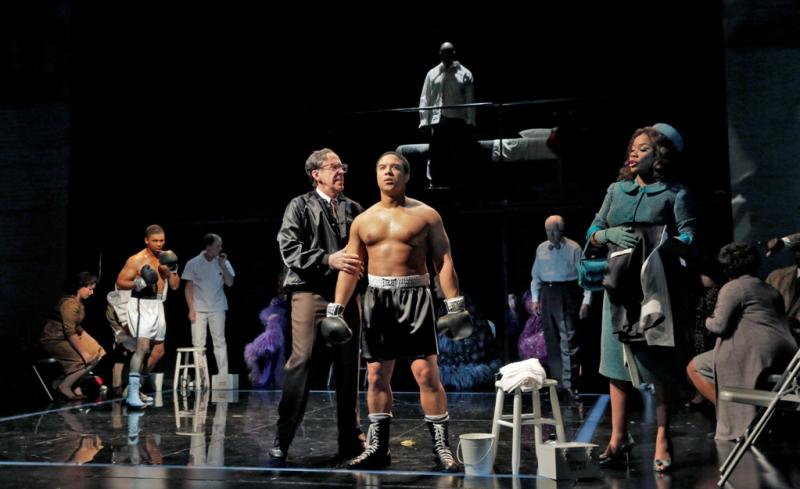

Here the social and cultural trajectory of African-American musical theatre could be perfectly plotted by putting Champion up against a work such as The Life and Times of Malcolm X by fellow jazz-composer Anthony Davis, making clear how the middlebrow will always finally trump the experimental. That said, Champion, especially in this strikingly designed production by Allen Moyer, provides a highly enjoyable bitter-sweet evening of vintage Americana, and an ultimately moving tribute both to a brave man's tragic existence and to the creative collaboration of two equally matched and equally multi-talented artists.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Add comment