Classical CDs Weekly: Britten, Debussy, Hindemith | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs Weekly: Britten, Debussy, Hindemith

Classical CDs Weekly: Britten, Debussy, Hindemith

British concertos, French impressionism and German violin music

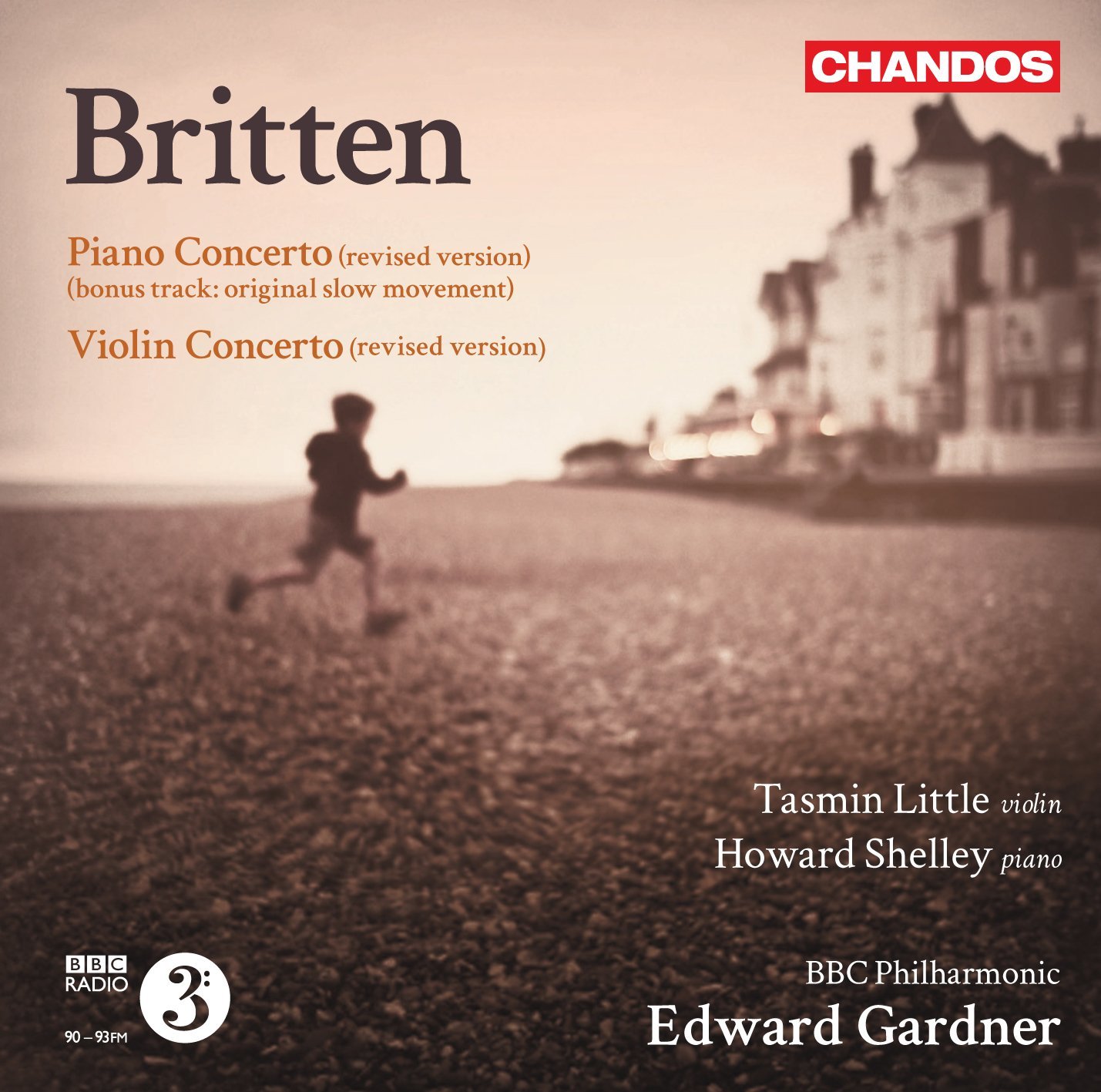

Edward Gardner starts Britten’s Piano Concerto with amazing ferocity and drive. Winds and horns make light work of their repeated quavers, and Howard Shelley relishes the fast tempo when he makes his entrance a few seconds in. What a fabulously entertaining work this is, but don’t search for profundity. The sardonic edge that’s found in several early Britten works is never far away, but there’s so much wit and energy, and there are several moments where Britten can’t resist turning on the charm. There’s a beguiling soft tutti passage following the thunderous first movement cadenza, with solo woodwinds tiptoeing through a sequence of unlikely chords – technically simple, but accomplished with great flair. It’s a large-scale piece, but without a wasted note. Shelley excels in the third movement Passacaglia, where Britten’s neat harmonic progression is treated to several unlikely transformations. The March is thrilling, and leaves an appropriately unsavoury aftertaste. Gardner and Shelley provide a bonus in the shape of Britten’s original third movement, a Recitative and Aria. It’s fun, though maybe a little too clever for its own good; Britten’s decision to axe it was correct.

The coupling is Tasmin Little's account of the emotionally-charged Violin Concerto. I’m still reeling from the impact of James Ehnes’s recent Onyx disc with Kyril Karabits. Little is technically just as assured, and her tone is gorgeous. But her interpretation feels less intense, and the closing minutes of the finale don’t carry the same weight. All else is marvellous – white-hot playing from the BBC Philharmonic and close-up, widescreen Chandos sound.

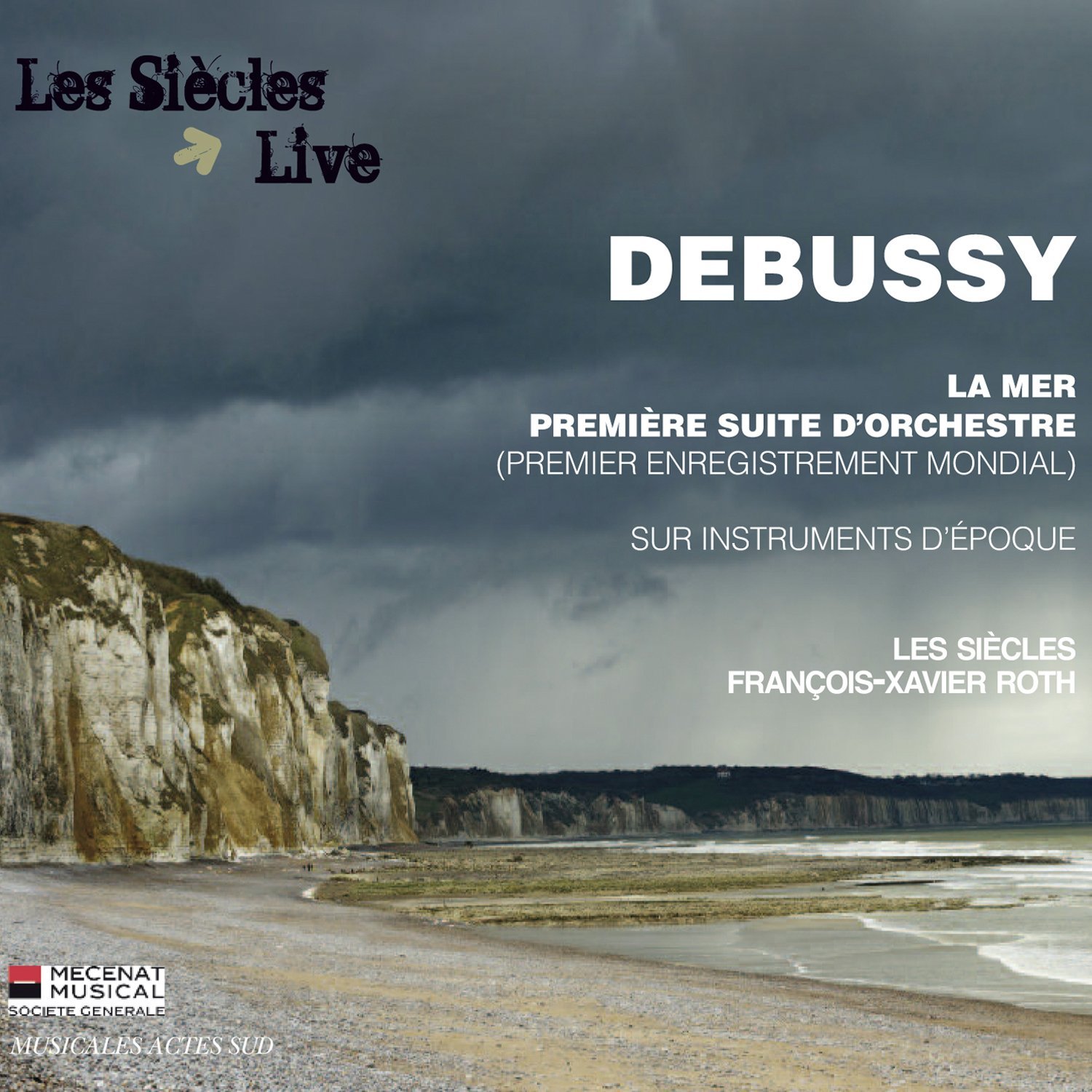

Jos van Immerseel’s enjoyable period-instrument version of Debussy’s La Mer appeared a few months ago, and here’s another from François Xavier-Roth’s Les Siècles. Their La Mer is not radically different from van Immerseel’s – there’s a bracing salty astringency to some of the string playing, and solo winds and narrow-bore brass cut through the textures with style. It’s the quieter moments which linger in the memory – wonderful soft percussion playing, and the delicate coda to Debussy’s excitable second movement is brilliantly handled. The closing pages are suitably wild and ecstatic, though I’m always disappointed when the spiky trumpet fanfares cut by Debussy aren’t reinserted.

Debussy’s Première Suite d’Orchestre receives a first recording here; a student work completed in 1880 and thought lost for many years. A piano-duet version was published in 2008, and the third movement was orchestrated recently by musicologist Philippe Manoury. Much of the music is delectable fluff; lots of faux-exotic touches and offbeat tambourine strokes. That the third movement Rêve sounds so decadent might be due in part to Manoury’s scoring, full of diaphanous string chords and hazy woodwind themes. Debussy’s Cortège et Bacchanale closes proceedings with brash vigour. Not top-drawer music, but highly entertaining, and beautifully delivered by Xavier-Roth’s players. Tasteful sleeve art too - unusual for this team's CDs.

Never underestimate Paul Hindemith’s music. The temptation is to dismiss him as a lumbering, workmanlike 20th century composer, churning out dry instrumental sonatas rarely heard outside the examination room. Hindemith’s rarely heard Violin Concerto is dramatic, lyrical and accessible. It was completed in 1939, just before Hindemith left Germany for the United States. Frank Peter Zimmermann’s bold, gutsy reading makes light work of the technical challenges, placing the work firmly in the Germanic tradition. Hindemith’s dense, Brahmsian orchestration, the huge brass eruptions apart, sounds unusually transparent under Paavo Järvi - listen with open ears and you’ll be moved and beguiled. By the soloist’s extended cantilena in the second movement, and the skittish dance figurations in the finale. Hindemith’s very individual use of tonality is heard at its most characteristic, every affirmative cadence sounding both surprising and inevitable.

There’s a delightful, compact sonata for solo violin too, the opening phrases of which aren’t a million miles from The Lark Ascending. More substantial are three sonatas for violin and piano. An early two-movement work from 1919 is witty and accessible. The 1935 Sonata in E opens with a graceful theme which could only have come from Hindemith’s pen. The Sonata in C is the best of the lot – hearing Zimmermann and pianist Enrico Pace blast out the closing minutes of the final fugue is a profound, spiritually uplifting experience. Astonishingly vivid sound adds to the impact.

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Add comment