The Woody Allen story: 'Why do I feel like I got screwed?' | reviews, news & interviews

The Woody Allen story: 'Why do I feel like I got screwed?'

The Woody Allen story: 'Why do I feel like I got screwed?'

Robert B Weide's film on Woody Allen is full of insights. He explains how he got the story

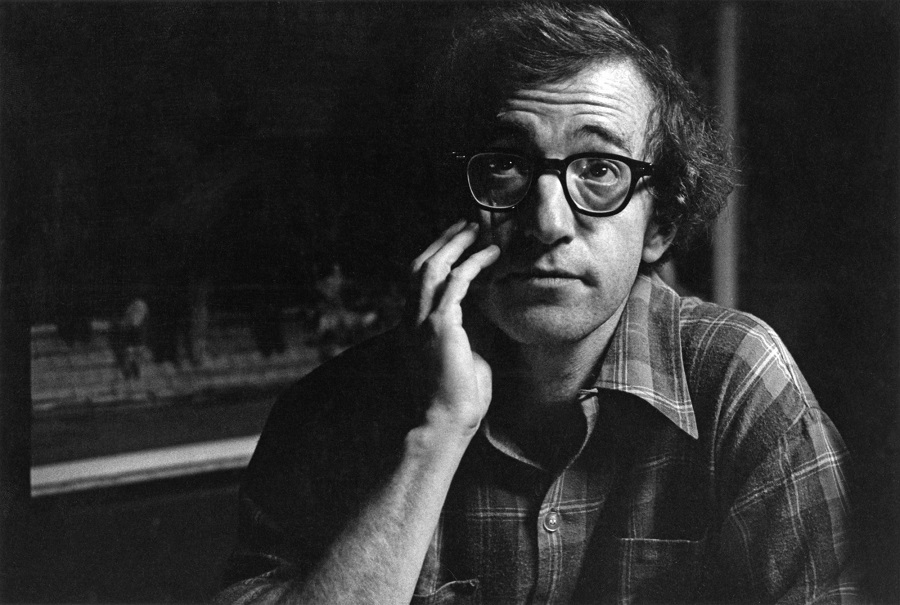

Woody Allen once joked that he would prefer to achieve immortality not through his work but through not dying. He is now 77 and the inevitable is a lot nearer than it was when he first realised, aged five, that this doesn’t go on forever. Fear of death has powered the furious productivity that in the early days yielded jokes by the yard, then the films appearing year upon year.

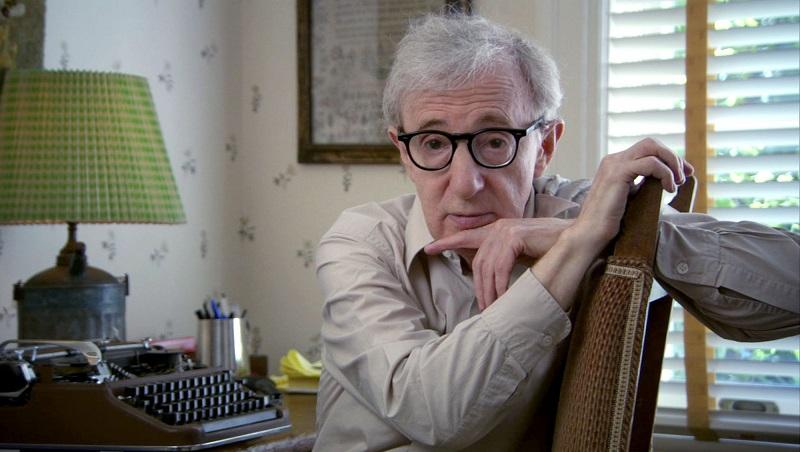

Robert B Weide has made films on the Marx Brothers and Mort Sahl (as well as directing Toby Young's How to Lose Friends and Alienate People and many episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm). He first attempted to add Woody Allen to his roster of subjects in 1982. The answer was a polite no. He kept asking roughly every decade until in 2008, at the fourth request, Allen finally capitulated. The resulting interview is shown as part of Imagine this week, was first shown in the US in November 2011. It was criticised in some quarters as a hagiography, and arguably it does soft-soap the notorious phase of Allen’s life when the custody battle with Mia Farrow found him migrating from the arts page to the front page. And yet Weide managed to penetrate one of his film sets to watch Allen at work, to lure Allen back to the old neighbourhood in Brooklyn, and even conducted much of the interview in Allen’s bedroom, where he writes his scripts on his bed and types them up at his desk.

These are not privileges vouchsafed to previous interviewers, and for all dedicated Allenologists they yield fascinating new insights. There are interviews with an all-star cast including all his regular collaborators and key performers. Indeed only three names are missing from that list: his first wife Harlene, his third wife Soon-Yi, and Farrow. Farrow’s absence was to be expected, but she did grant permission for clips featuring her to be used. Without them, it would be less than half the film. Robert B Weide tells theartsdesk how he got the story.

Watch the trailer to Woody Allen: A Documentary

JASPER REES: When did you know that he was finally going to capitulate after nearly three decades of saying no?

ROBERT B WEIDE (pictured below right): In 2008 I wrote him a letter and really made the case that this film should be made and I’m the one to make it. And I thought if he does anything but slam the door closed I’m going to be like a pit-bull on a postman’s leg. Interestingly the phrasing from his assistant was “Woody wants to know, if he wants to do this.” I said, “I’m in.” He kept the door ajar. The “if” was very reasonable stuff: what would I need him to do, would I need to interview him, would I need to be on the set, where would the film be shown? I think what worked in my favour is that Woody and I share a lot of the same cultural heroes so he had seen a lot of my films, not because he was interested in me but because he was interested in the subject matter. I never really asked him why he gave in but I wrote a hell of a letter.

I never acted deferential around him and somehow the emails fell into this very sort of chummy kind of sarcastic relationship where we sort of took the piss out of each other. I would write and say, "Would you consider x, y and z?" And he’d write back and say, “What, are you some kind of an idiot?” and I would write back and say, “Listen, Jew boy, get off your high horse.” So by the time we sat down with each other the ice was broken. He wasn’t reticent and I wasn’t nervous.

I never acted deferential around him and somehow the emails fell into this very sort of chummy kind of sarcastic relationship where we sort of took the piss out of each other. I would write and say, "Would you consider x, y and z?" And he’d write back and say, “What, are you some kind of an idiot?” and I would write back and say, “Listen, Jew boy, get off your high horse.” So by the time we sat down with each other the ice was broken. He wasn’t reticent and I wasn’t nervous.

How did you persuade him to get into the car and take the tour of his childhood haunts?

His first response was “I can’t imagine anyone is going to care where I grew up or where I went to school or where I played stickball in the streets. If you want to film it, fine, but I think it’s going to be very boring.” I said, “If you’re watching a documentary about someone you admire like Groucho or Bergman or Fellini or Sidney Bechet, wouldn’t you be interested in seeing them go through their old neighbourhood and see where they grew up?” He said, “No! I would just be interested in their work.” I said, “Trust me.”

And yet with his films he goes back to his own childhood in Annie Hall and Radio Days so plainly regards them as interesting enough in a cinematic context. Did you read that as a kind of defence?

And yet with his films he goes back to his own childhood in Annie Hall and Radio Days so plainly regards them as interesting enough in a cinematic context. Did you read that as a kind of defence?

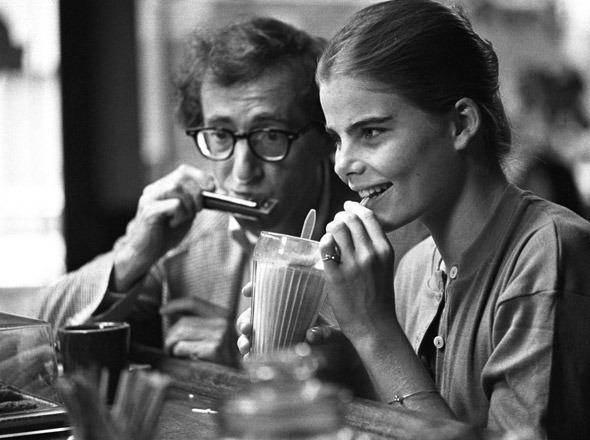

No I think it’s genuine. I don’t think he puts it on to seem modest. He always downgrades his own films and thinks they’re not that great. He thought he’d botched Manhattan (Allen pictured with Mariel Hemingway) so badly that he said to United Artists, “I’ll do the next one for free if you don’t release this.” This isn’t a guy who’s pretending to not care for his own work. The same is true of these other areas. He’s very shy. He thinks he’s had a bit of luck, he thinks some of his films have come out OK, but when he sounds that self-deprecating he’s grading on a curve: he’s grading himself against all the great world filmmakers, Bergman and Kurosawa and Fellini, that he grew up loving and still loves to this day. And he says, “Compared to them I’m a little nothing filmmaker.”

Overleaf: 'His emails prior to watching it were very very funny'

Did you get a sense that he fundamentally despises the fact that he’s funny? Does he set any value on being able to make people laugh?

I think he really undervalues the importance of comedy which is a very odd thing for him to do considering I know how important the Marx Brothers and WC Fields, SJ Perelman and Robert Benchley and Mort Sahl have been in his life. I came to believe that he really means it. He still thinks that great dramatic work is more meaningful than comic work. He just has a natural knack for comedy. When he was 15 he was writing 50 jokes a day for these columnists. It came real easy to him. That’s the coin he deals in because that’s where his ability is. He’s the first person to say, “I’m not good at drama, I try, I fail more often than not, so I do comedy.” With Crimes and Misdemeanours he came very close to yanking out all the comedy. He just wanted to focus on the murder story with Anjelica Huston and Martin Landau. He thought the comedy stuff was just a throwaway. But what people love about that film is the blend between the two.

Mia Farrow does not participate in the documentary of a career in which she played an integral role. How hard did you push it? (Pictured left, Farrow watching the big screen in The Purple Rose of Cairo)

Mia Farrow does not participate in the documentary of a career in which she played an integral role. How hard did you push it? (Pictured left, Farrow watching the big screen in The Purple Rose of Cairo)

I knew she wouldn’t but I wanted it to be her decision. She considered it but “ultimately she feels she is going to have to pass”. And I’ll tell you what she did do which is critical to me: Mia had to sign off on my using all that material. I thought, if I can’t get her OK on this I’m sunk. I told her I said I’m certainly going to address the relationship and the break-up because if I don’t it looks like a whitewash, and I wasn’t saying this to placate her or Woody. I really didn’t want to dwell on it, I wanted to cover it in the sense that I thought was journalistically responsible, but I wasn’t going to let the film turn into a courtroom drama. I said, “I just can’t imagine doing the film without talking about these 12 years of this brilliant collaboration.” She signed the release. I thought that was remarkable.

How did you approach Farrow’s break-up with Allen?

I dealt with the whole media circus element of it and how this become tabloid fodder and the court battles of the kids, the hearings, and [how] Mia got custody and he kept his nose to the grindstone and kept making films. I’ve seen interviews where the answers are unsatisfying and they can only be unsatisfying, when people say, “How did you feel when Mia got custody?” What’s he supposed to say? “Oh I felt great.” So I didn’t bother asking him how he felt about these things. I just had him walk through it. I did say things like, “Did the thought occur to you that the end result of all this was that you might not get finance on your films any more?” He really didn’t care. People would like his movies, not like his movies, like him, not like him: if he lost his financing, as improbable as that seemed to him, he could still write plays or short stories. He and I happen to have the same lawyer and when all this happened in 1992 Woody said to him, “This will blow over in a couple of days. I’m not a big enough celebrity for this to have meaning anything for more than its initial shock value.” My lawyer said, “Are you kidding? You have no idea what this is going to become.” And Woody was genuinely surprised by it.

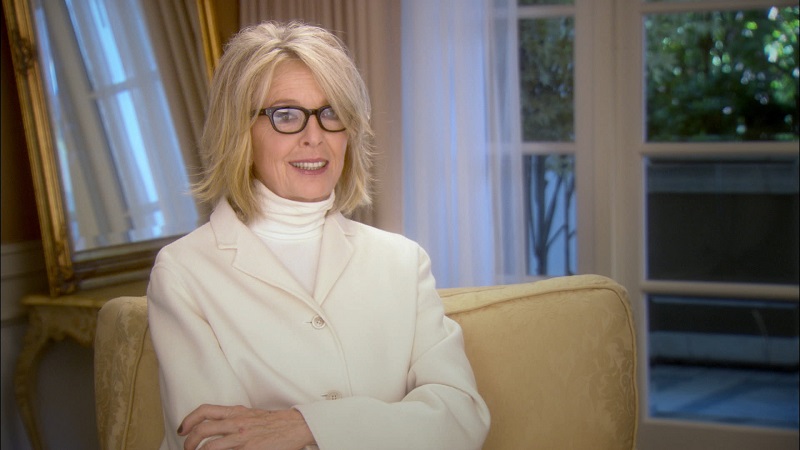

His closeness to Diane Keaton (pictured left) is nicely captured in the lovely clip from the set of Sleeper where he keeps corpsing as she impersonates his mother. And yet she says in the film, “He didn’t quite fall in love with me but I was around a lot.” What do you think she means?

His closeness to Diane Keaton (pictured left) is nicely captured in the lovely clip from the set of Sleeper where he keeps corpsing as she impersonates his mother. And yet she says in the film, “He didn’t quite fall in love with me but I was around a lot.” What do you think she means?

That I had only because at the time of Sleeper there is one of those 10-minute profiles on 60 Minutes. I happened to have a personal connection to one of the old-guard CBS 60 Minutes guys and said, “Is there any chance that the dailies or the rushes are archived anywhere?” Two days later I got an email saying, “There are 16 video cassettes in my office right now that say ‘Woody Allen’ on them. Where do you want me to ship them?” God bless him. There is a scene of Diane cracking him up and obviously that was the one I was going to be using. When have you ever seen Woody Allen just not being able to stop laughing? Obviously that was a very loving deep relationship between the two of them. I think that was her observation that he was in there but not in there all the way.

Did you ask Soon-Yi for an interview?

Did you ask Soon-Yi for an interview?

I did. She turned me down too. It was through Woody. She was very much on camera in Wild Man Blues [the documentary about Allen’s jazz band on tour, pictured left] but that’s not like talking or reminiscing. He came back and said, “Soon-Yi is going to pass. She just really doesn’t like to do anything that puts her in the spotlight.” It is really cute to watch them together. She really does look after him. He becomes the child and she takes care of him. He is very unsentimental about a lot of things like birthdays. I’d say, “What are you going to do about your birthday?” He says, “I’d be happy just to ignore it and stay in the editing room but for my wife and kids it’s an excuse to go out and eat steak.” But there are many times I would call him up and say, “Can we do this interview on Tuesday morning?” And he’s say, “Well, I walk my kids to school at 8.30, I’ll be back by nine, so if your crew wants to get here…” Another day he said, “We have to be finished by two because I’ve got a parent-teacher conference at the school.” So he does run off and do that stuff.

He is famously reluctant to watch his own films after release. Did he watch your film about him?

He had to watch it once. He was very apprehensive. He was afraid it would come off as a tribute and that he would seem complicit. He at one time tried to talk me into doing it without him participating in it. Again, he wasn’t kidding around. He totally stayed out of it during editing. I really didn’t want anyone going on about what a genius he is. I think Mira Sorvino sneaks in the G-word once. Some people comment on the Internet that it’s a bit of a hagiography. I don’t really think it is. But you interview these people who worked with him who like him – they’re going to say positive things about him. But I have people talking about not such positive things too. His emails prior to watching it were very very funny. He talked about having paramedics on board and oxygen if he needed it. He really thought he was going to have a panic attack. The great line I got from him was, “I’m 76 years old and you’re the first person who has come along and humanised me and that includes several shrinks.”

You end with his conclusion that he’s led this charmed life in which everything worked out, “so why do I feel like I got screwed somehow?” Why does he feel like that?

It’s just that existential angst. It’s no mistake that the film virtually opens with him talking about his realisation at the age of five that this was finite, and then you’re nothing. I think that informs everything. It not only is an underpinning to most of his work but it’s the great theme in his life and why he’s so prolific. He’d rather be contemplating problems in the editing room than these bigger, more threatening questions. That’s why he will continue making films until he is physically unable to do it.

- Woody Allen: A Documentary is on BBC One on Tuesday and Wednesday at 10.35pm

- Watch clips from the film on the BBC website

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

Add comment