David Frost, giant of the small screen, dies | reviews, news & interviews

David Frost, giant of the small screen, dies

David Frost, giant of the small screen, dies

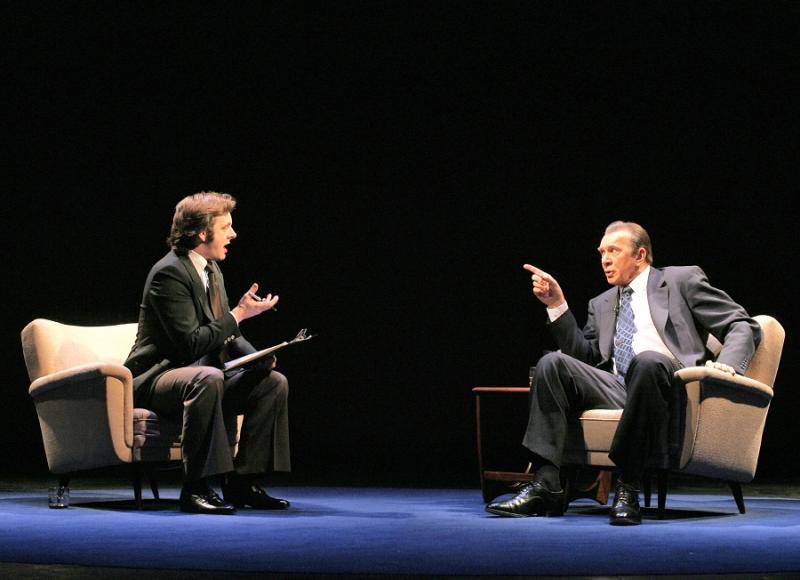

Few interviewers see themselves fictionalised. In this interview Frost recalled the experience

David Frost, who has died at the age of 74, was a character. The obituaries will tour the entirety of his career as swinging young presenter of TW3, as the first transatlantic celebrity of the gogglebox who gave his name to a sugary brand of Kelloggs cereal, and as a lifelong thorn in the side of Peter Cook. Then there was Through the Keyhole and the TV-am cataclysm later followed by his Sunday morning resurrection on the BBC.

Peter Morgan’s play Frost/Nixon had concluded its run at the Donmar Warehouse and was moving into the West End. (It would subsequently go to Broadway and be made into a film by Ron Howard - see trailer below). So momentous were Frost's sessions with the disgraced former president that they more than earned their two hours on the stage. And Frost decidedly contributed to the drama. As imagined by Morgan and the actor Michael Sheen, his gift for showmanship went hand in glove with a sharp understanding of the power of television.

I met Frost in his office at the far end of Kensington High Street, a few floors up a cramped lift. By this time he had vacated his seat on Sunday mornings and was working for Al-Jazeera. His mainstream career, in effect, was over, and there was a sense that his legacy had been placed in the hands of a bunch of theatremakers. Sir David (he was knighted in 1993) was evidently in two minds about Frost/Nixon. He first saw it at an early preview.

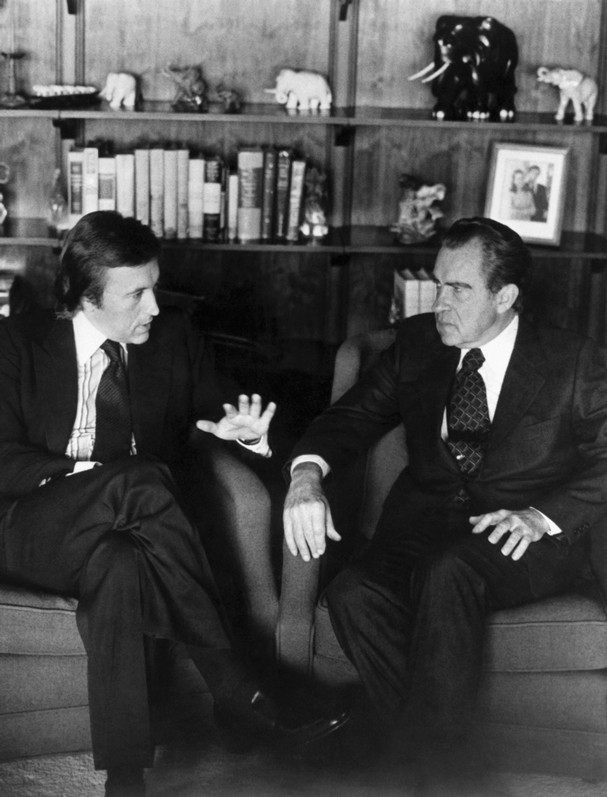

Watch Frost grill Nixon for real

“I was very curious to find out what my reaction would be,” he recalled. “They didn’t tell the cast I was in. Michael [Sheen] said that they were all bewildered because the audience for the first 20 minutes seemed nervous and there was less response. I don’t know whether people expected me to leap up and say, ‘Stop! That’s not true!’”

A Methodist minister’s manse is by no means a castle but I never felt I was born on the wrong side of the tracks

Not that this would have done him much good. At the initial meeting, he dithered on the issue of artistic control. “They felt that it would have less credibility if I had ultimate editorial control.” Did he agree with them? “Yes I did, 51-49. But I think it would have been OK the other way. I’m delighted it’s had such an enormous success. Obviously I would have preferred that it be accurate as well.”

The so-called inaccuracies were mostly designed to enhance and underline the drama. The interviews took place over 12 days, for example, and what Frost called Nixon’s “amazing mea culpa” over Watergate was covered over two days (rather than one) halfway through. Morgan explicably switched these climactic exchanges to the end. He also externalised the fears of both men in an entirely fictional phone call Nixon makes to Frost on the eve of battle, in which he suggests that for the loser the wilderness beckons.

“That one piece of fictionalising is a masterstroke,” said Frost. “It captures the Nixonian self-pity and his sense of being the wrong side of the tracks.” He was slightly less comfortable with the idea that, as Nixon suggests in the same one-sided conversation, the pair of them have a common bond as social outsiders. “Maybe Peter were trying to link us together to make the drama of the actual finale that much greater. A Methodist minister’s manse is by no means a castle but I never felt I was born on the wrong side of the tracks.”

Frost was not persuaded by another creative element in the play’s psychoanalysis of Nixon. The fictional Frost concludes from that phone call that Nixon is subconsciously asking for the wilderness. “The Frost character says, ‘He wants me to finish him.’ I don’t think that’s remotely true but it’s a good line. I don’t think Nixon was that generous.”

Frost was not persuaded by another creative element in the play’s psychoanalysis of Nixon. The fictional Frost concludes from that phone call that Nixon is subconsciously asking for the wilderness. “The Frost character says, ‘He wants me to finish him.’ I don’t think that’s remotely true but it’s a good line. I don’t think Nixon was that generous.”

There were only a couple of moments where Frost would have stuck his oar in if he could. The play implies, for example, that in 1977 his career had gone into almost as steep a decline as Nixon’s. According to Frost/Nixon, a series in Australia had only just been scrapped, as had his New York talk show. Not according to Frost. “It’s a detail, but I did specials whenever I went out to Australia, so there was no series to be cancelled. And The David Frost Show [in America] was 750 editions but it ended some years before, in June of ‘72. All those things gets compressed.”

The play also suggests that in the tortuous pre-broadcast negotiations, Frost as producer caved in to all the demands of Nixon’s flamboyant representative, Swifty Lazar. “Most of the things [Lazar] asks for in the play in fact he didn’t get. Nixon didn’t know any of the questions in advance. He didn’t see the edited programme till it was broadcast. And we had not four hours [of interview] but 28 and three-quarter hours. If you have him asking for it one probably ought to see him not getting it.”

As the interviews progress, in the interests of drama Morgan suggests that Nixon is besting his interrogator with long filibustering answers, one of which lasts 23 minutes. “Well I mean that’s dopey. In television three minutes is an eternity and even someone who had never conducted an interview before would ever let anybody, including the President of the United States, go on for 23 minutes.”

However, when the play gets to the meat, Morgan scrupulously portrays Frost’s brilliant interview technique and Nixon’s remarkable capitulation. It’s an electrifying encounter, and it’s electrifying to hear Frost, and perhaps not quite the all-action interviewer superhero he was 30 years earlier, retell it in his book-lined office.

“The first day,” he recalled, “where he wouldn’t even admit to mistakes, was a disaster from their point of view. By the second day he had the haunted look that he had in the final days when he was battling not to be removed from office. He was prepared to volunteer something because he realised he had to. He got as far as ‘mistakes’. I said to him, ‘But won’t you go further than mistakes? The word doesn’t seem enough for the American people.’ And he said, ‘Well, what word would you suggest?’ which was a heart-stopping question because I sensed that he was more vulnerable at that moment than he’d ever be again.

“And so I threw away my clipboard to indicate this wasn’t a carefully prepared ploy and I just said, ‘There’s three things I think people want to hear you say. First of all that you went to the very edge of the law and there was wrongdoing. Second, that you betrayed your oath of office. And third, that you put the American people through two years of needless agony and you apologise for that.’ And I said, ‘Now I know that it is more difficult for you than almost for anyone to apologise, but you’ve got to do that and if you don’t you’ll be haunted for the rest of your life.’ Over the next 20 minutes he responded to those three things. And when he said, ‘I let down the American people, I let down the whole system of government, the hopes and dreams of all those young people,’ one was incredibly aware of something very significant having happened.”

For my final question I asked Frost if he actually found himself liking Nixon. “Like Nixon, the word ‘like’ is too intimate,” he said. “Nixon was so withdrawn from human contact. I was able to empathise at times. But there were 20 or 30 people in jail because of his actions. He was a sad man who wanted to be great."

- Sir David Frost, 7 April 1939 – 31 August 2013

- Michael Sheen on portraying David Frost

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment