American Psycho, Almeida Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

American Psycho, Almeida Theatre

American Psycho, Almeida Theatre

Bret Easton Ellis-inspired musical stares scarily and scintillatingly into the abyss

Among the multiple achievements of American Psycho, any one of which might be enough to make Rupert Goold's long-awaited Almeida season-opener the banner musical of a notably busy year for the form, a particular paradox deserves mention up front. Here's a piece steeped in material (the Bret Easton Ellis novel from 1991 and its film version nine years later) that fetishises surfaces and wallows in emptiness and that - a grand hurrah! - turns out itself to have a lot to say.

I had feared in advance that the show might devolve into a blank celebration of late-Eighties blankness as per the book but not at all. By turns devastating and quick-witted, scintillating yet unexpectedly moving, the piece raises all sorts of hopes for Goold's embyronic Almeida tenure and - far more importantly - for renewing interest in a genre that has been running in place for far too long.

Indeed, so dim-witted have been most of this year's musical premieres (The Light Princess, whatever its imperfections, very much the welcome exception) that one began to wonder whether our smarter theatrical talents had all but given up on the genre. And now along come Goold and a mighty collaborative team to shake a too-often stillborn field of theatrical endeavour back to life. And if their success exists in the service of signalling the deathly impulses of a deadened society embodied by that bloodsoaked Wall Street whiz kid, Patrick Bateman, so be it. The show's characters may sing a rhymed paean to their unironic affection for Manolo Blahnik, but the irony here is that a musical staring directly into the abyss should emerge as murderously entertaining. And affecting, too. (The production arrives as a co-venture between the Almeida, the touring company Headlong, and Act 4 Entertainment.)

Goold's skill lies in suggesting and then sustaining an ever-shifting reality for a story that can allow Matt Smith's charismatic yet chilling Bateman (pictured right) to address the audience one minute, be matey with his coke-snorting, pec-pumping fellow financiers the next, and weave his way among an array of beautiful women whom he can't entirely decide whether he wants to bed - or behead. And though one thinks perhaps inevitably of Sweeney Todd (a machete is raised in murderous anticipation just as Sweeney does his razor), there's something rather more Woyzeck-like about the gathering disintegration of a soul in freefall: a man who sends out ceaseless warnings to others of the threat he represents only to find himself carried aloft by his ripped abs and way with a business card, two societal obsessions unknown in Sweeney's day.

Goold's skill lies in suggesting and then sustaining an ever-shifting reality for a story that can allow Matt Smith's charismatic yet chilling Bateman (pictured right) to address the audience one minute, be matey with his coke-snorting, pec-pumping fellow financiers the next, and weave his way among an array of beautiful women whom he can't entirely decide whether he wants to bed - or behead. And though one thinks perhaps inevitably of Sweeney Todd (a machete is raised in murderous anticipation just as Sweeney does his razor), there's something rather more Woyzeck-like about the gathering disintegration of a soul in freefall: a man who sends out ceaseless warnings to others of the threat he represents only to find himself carried aloft by his ripped abs and way with a business card, two societal obsessions unknown in Sweeney's day.

The British stage behemoth remains for many (especially in the Manhattan where American Psycho is set) a symptom of the bloated excesses of an age that lives on in its long-running musicals, and there's a neat gag involving Broadway tickets to Les Miserables as the ultimate status symbol of the day - well, along with a reservation at Dorsia, an eatery invented for the film (though an actual one does now exist in London). Whether it's an aerobics class or a bar or a pop-up cab from beneath the stage floor, the production utilises two revolves to move us among many a gleaming if faceless environment whose absence of colour in Es Devlin's characteristically keen-eyed design exists in cruel contrast to the carnage that will ensue. The violence, when it arrives, constitutes a knockout blow, making for a first-act curtain to prompt thoughts of what might have happened had Goold ever got his hands on the perpetually ill-fated stage musical of Stephen King's Carrie. (As it is, there's a nod to Goold's own Macbeth in the extent to which Bateman's victims live on to haunt him.)

Musically, Duncan Sheik's score suggests a synth-heavy amalgam of Depeche Mode by way of Giorgio Moroder, and if Smith isn't much of a singer (let's just say one wouldn't pay to see his Billy Bigelow), the Doctor Who star's somewhat off-kilter sound is perfect for Bateman's own sidelong glance at the society he wants to send to the slaughterhouse. Such period hits as are heard - whether from Huey Lewis & the News or Tears For Fears or one or two others - authenticate proceedings without, thank heavens, leading us down the jukebox musical road.

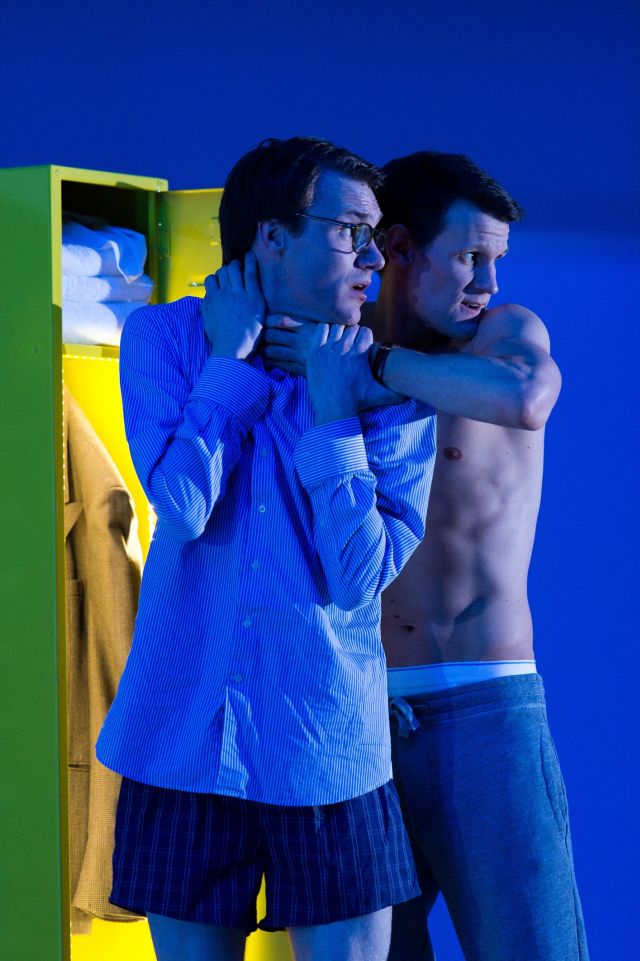

In acting terms, Smith's performance is a marvel, proffering an increasingly anxious and self-loathing narcissist who, far from meeting his comeuppance, represents just the sort of unknowable charmer who may walk among us still, attracting both sexes along the way (pictured left, Smith and the excellent Hugh Skinner as Bateman's closeted colleague, Luis). The ensemble as a whole function both as the grasping citizenry of a particular time and place and as a series of sharply individuated turns, with Katie Brayben, Susannah Fielding, and Cassandra Compton all outstanding as three women willingly drawn into the web of a seducer who parades his absence of affect to anyone who will listen. I mean, would you turn away someone who lays claim to having a "severely impaired capacity to feel" when he looks so good in (and out of) a suit?

In acting terms, Smith's performance is a marvel, proffering an increasingly anxious and self-loathing narcissist who, far from meeting his comeuppance, represents just the sort of unknowable charmer who may walk among us still, attracting both sexes along the way (pictured left, Smith and the excellent Hugh Skinner as Bateman's closeted colleague, Luis). The ensemble as a whole function both as the grasping citizenry of a particular time and place and as a series of sharply individuated turns, with Katie Brayben, Susannah Fielding, and Cassandra Compton all outstanding as three women willingly drawn into the web of a seducer who parades his absence of affect to anyone who will listen. I mean, would you turn away someone who lays claim to having a "severely impaired capacity to feel" when he looks so good in (and out of) a suit?

I wish Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa's book didn't feel the need on occasion to announce its themes, and my heart sank at a reference early on to the "American dream" (no, people, not everything on God's capitalist earth can be subsumed under that banner); at the same time, some economic moralising near the end unhelpfully calls to mind the (far inferior) Goold-directed Enron. There will of course be those who take the show purely at the level of its "murders and executions" wordplay, which I suppose is fine. But listen out, and I suspect you'll hear an electronic music-led lamentation that reaches well beyond the topical references in which the musical gleefully, sometimes glibly trades. And as for the evening's bravura star, don't stare into those eyes too long: looks, as Patrick Bateman would be the first to tell you, can indeed kill.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review – compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit Farm Hall

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review – compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit Farm Hall

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment