Classical and Opera 2000-9: The Highs and Lows | reviews, news & interviews

Classical and Opera 2000-9: The Highs and Lows

Classical and Opera 2000-9: The Highs and Lows

The ups and downs of a musical decade

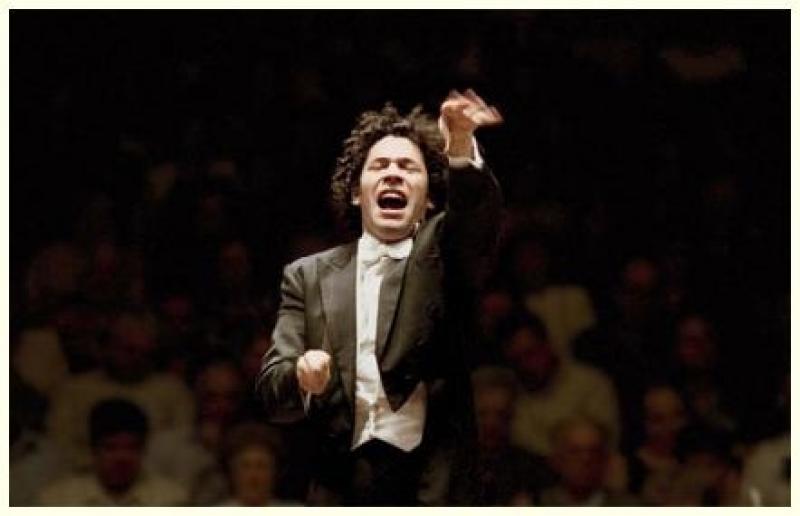

No great new movements or radically transformational figures emerged to dominate classical music in the Noughties (not even him up there). Just one small nagging question bedevilled us: will the art form survive? Well, it has. What appeared to be a late 20th-century decline in audience interest in the classical tradition was in fact a consumer weariness with the choices on offer.

David Nice's Highs

Most exciting formation of the decade: the 2003 re-birth of the Lucerne Festival Orchestra under Claudio Abbado, who made it a crack band of players he knows and loves from veteran cellist Natalia Gutman to members of the Hagen Quartet and a core of the Gustav Mahler Chamber Orchestra. Their Mahler symphonies in Lucerne and London, also captured on DVD, have consistently shown vital music-making of a perfection it’s not possible to surpass.

Most exciting formation of the decade: the 2003 re-birth of the Lucerne Festival Orchestra under Claudio Abbado, who made it a crack band of players he knows and loves from veteran cellist Natalia Gutman to members of the Hagen Quartet and a core of the Gustav Mahler Chamber Orchestra. Their Mahler symphonies in Lucerne and London, also captured on DVD, have consistently shown vital music-making of a perfection it’s not possible to surpass.

Just as bracing in a different way is the Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela, flagship of the country’s amazing educational sistema. It’s actually been around for longer than the pundits like to think; it took a conductor of equal charisma who rose from the ranks, Gustavo Dudamel, to give the orchestra a sexy, media-friendly image. Their 2007 Prom had the fizz and energy of a pop concert; and why not? Best of all is the change, world-wide, in musical education for kids. It’s happened, and it’s spreading still. Director of the decade: Richard Jones. Makes the serious funny in an uneasy kind of way, and the funny worth taking seriously. From his baked-beaned Wozzeck (OK, I’ll settle for that, and the revelation of Christopher Purves’s hair-raisingly tormented soldier) for Welsh National Opera to his Young Vic Annie Get Your Gun (go before it ends on 9 January), he always comes up with something new; you never know what you’re going to get. Even the shows he thinks didn’t work – Horvath’s Tales from the Vienna Woods at the National and Weber’s Euryanthe at Glyndebourne – offered plenty of food for thought.

Director of the decade: Richard Jones. Makes the serious funny in an uneasy kind of way, and the funny worth taking seriously. From his baked-beaned Wozzeck (OK, I’ll settle for that, and the revelation of Christopher Purves’s hair-raisingly tormented soldier) for Welsh National Opera to his Young Vic Annie Get Your Gun (go before it ends on 9 January), he always comes up with something new; you never know what you’re going to get. Even the shows he thinks didn’t work – Horvath’s Tales from the Vienna Woods at the National and Weber’s Euryanthe at Glyndebourne – offered plenty of food for thought.

Glyndebourne, though it can be as guilty as any house of putting on very ordinary shows, has a lot of highs to choose from. I’m torn between Melly Still’s bewitching opera-directorial debut with Dvorak’s Rusalka this season and Daniel Slater’s visual treat of a difficult-to-bring-off comedy, Prokofiev’s Betrothal in a Monastery, a couple of years ago. If I plump for the latter – and many critics hated it, while the audience had a great time every night – it’s because it fizzed under the baton of house MD Vladimir Jurowski, my conductor of the decade.

Glyndebourne, though it can be as guilty as any house of putting on very ordinary shows, has a lot of highs to choose from. I’m torn between Melly Still’s bewitching opera-directorial debut with Dvorak’s Rusalka this season and Daniel Slater’s visual treat of a difficult-to-bring-off comedy, Prokofiev’s Betrothal in a Monastery, a couple of years ago. If I plump for the latter – and many critics hated it, while the audience had a great time every night – it’s because it fizzed under the baton of house MD Vladimir Jurowski, my conductor of the decade.

Jurowski has to figure, too, as the energising force behind the renaissance of the London Philharmonic Orchestra both at Glyndebourne, where he has run the gamut from Rossini via Verdi and Wagner to Eotvos, and at the Royal Festival Hall. His one-year old series of festivals devoted mostly to one composer at the Southbank got off to a glittering start with an amazing concert performance of Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta, and seems to be bringing in younger audiences. If I have to single out one interpretation, it would be the roof-raising starburst of Schnittke’s Third Symphony only a month ago.

All the orchestras, capital and regional, are now in the hands of extraordinary chief conductors. I’ve only caught up with some of them in the last couple of years, but what sticks in the mind is the unbelievably nuanced and atmospheric playing Vasily Petrenko drew from the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra in Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances at the 2008 Proms. The just-released recording confirms this as simply the best performance of Rachmaninov’s surprisingly profound orchestral swansong I’ve heard; and competition is amazingly strong.

As for promise, it’s being realised here and now by Petrenko in Liverpool, Andris Nelsons in Birmingham, Stephane Deneve with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and Robin Ticciati at Glyndebourne and now the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. Again, difficult to pick one concert, but – perhaps because it’s so fresh – I was both knocked for six and moved to tears by the life Yannick Nezet-Seguin breathed into the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment’s Haydn symphonies in the Southbank’s Queen Elizabeth Hall.

As for promise, it’s being realised here and now by Petrenko in Liverpool, Andris Nelsons in Birmingham, Stephane Deneve with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and Robin Ticciati at Glyndebourne and now the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. Again, difficult to pick one concert, but – perhaps because it’s so fresh – I was both knocked for six and moved to tears by the life Yannick Nezet-Seguin breathed into the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment’s Haydn symphonies in the Southbank’s Queen Elizabeth Hall.

English National Opera now has a visual and an aural style to call its own. The visual side, especially in the newly ingenious use of video projections, ran in a line from Fiona Shaw’s double bill of Sibelius’s Luonnotar and Vaughan Williams’s Riders to the Sea to the musically questionable Saariaho L’amour de loin, the stunning Fura dels Baus Ligeti Le Grand Macabre and now Rupert Goold’s radical but justifiable new Turandot. Let’s not forget, though, that even in times of trouble the artists could be relied upon to deliver the goods. Much as I hated aspects of Phyllida Lloyd’s Ring cycle, I thought her Twilight of the Gods was easily the best I’ve ever seen, superbly moulded the night I went by young conductor Dominic Wheeler and featuring an incandescent performance by Kathleen Broderick.

Strong new operas are always thin on the ground. Interesting, but not wholly satisfying from the vocal point of view, have been Turnage’s The Silver Tassie, Ades’s surprisingly conservative The Tempest and Birtwistle’s grippingly produced and performed The Minotaur. Oddly, I enjoyed Barry’s screamily, queenily confrontational The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant more than any of those. The one that left me reeling, though, was James MacMillan’s The Sacrifice when Welsh National Opera brought Katie Mitchell’s searing production to London’s Sadler’s Wells. A surely ideal cast handled a score that proved singable without compromise. This is the one that deserves to last.

Antonio Pappano is only one among many inspirational musical leaders of the decade. Since, however, he’s had to run the biggest ship, and decided to cover everything from Mozart (Figaro from the harpsichord, wonderful) to Birtwistle, making more of The Minotaur intelligible than anyone thought possible, he has to take the laurels. I’m not sure he has the length and breadth of Wagner sorted yet, and I guess his Don Carlo was disappointing because he had to help several singers in trouble. But like Ed Gardner at ENO, he’s knocked the chorus and orchestra into top-notch shape. My memory for the earlier part of the decade has been failing me, so let’s settle for the auspicious date in September 2002 when he took up the reins with a glittering Strauss Ariadne auf Naxos. He’s stayed faithful to the radical director, Christof Loy, ever since.

A footnote: help! I’ve reached 10 and not singled out any singers, instrumentalists or chamber groups. Here’s just a little list of 10 more, picked off the top of my head and probably all too recent:

- the Jerusalem Quartet for making every work a miracle of communication

- Alban Gerhardt for the breadth of cello repertoire he’s revealed

- Anja Harteros, ideal Verdian soprano as Amelia in Simon Boccanegra and opulent Straussian, too

- audacious clarinettist Kari Kriikku for selling the contemporary so well

- Toby Spence for proving that the English tenor can move beyond the wet and weedy (no names here)

- the Rasumovsky Ensemble’s eight-strong Vivaldi Four Seasons, which I hadn’t been looking forward to

- Sarah Connolly for plumbing the Mahlerian and Purcellian depths as well as hitting the heights at the Last Night of the Proms, after a decade of great performances

- James Ehnes and Sir Andrew Davis for the perfect concerto partnership in a Philharmonia performance of Elgar’s Violin Concerto

- Alexander Melnikov and Rustem Hayroudinoff among pianists, only because they’re the two among many extraordinary young Russian-trained soloists who seem to have had the least recognition.

David Nice's Lows

I’m going to sound Pollyannaish and claim that the good has been infinitely more memorable than the bad – which, of course, is not the same as mediocre - so I’m not stumping up a list. We all know who the bad singers on the fringes of the serious-music world are, or were; what more can I say than that listening to them might just encourage newcomers to explore the repertoire a little further?

The worst thing to happen to so-called "classical music" this decade was its increasing marginalisation in the serious papers, so hoorah for The Arts Desk and what’s good about the blogosphere. Nothing much, it seems, can be done about its perception on telly; despite the advent of BBC Four, coverage outside Proms season is dismal and documentaries usually end up being patronising in the extreme. As for Late Review, or whatever they call that slot on BBC Two’s Newsnight, what does it take to get something featured alongside the films, the exhibitions and the plays? The last time I tuned in was when there was no-one to speak up for The Minotaur, and one of the pundits infamously declared something along the lines of "if you think classical music is dead, go along to Covent Garden and view the corpse". Well, the corpse is alive and kicking.

Igor Toronyi-Lalic's Highs

Simon Rattle and Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Festival Hall, October 2002

Simon Rattle and Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Festival Hall, October 2002

In the summer of 2002, Simon Rattle became the first Briton to head the world’s greatest orchestra. We awaited his first visit to London with his new band with pant-wetting nervousness. My only thought was that if he cocked it up, the Berliners would surely never go British ever again. Thankfully the two South Bank performances, which included of Mahler’s Fifth and Bruckner’s Ninth, blew the audiences away.

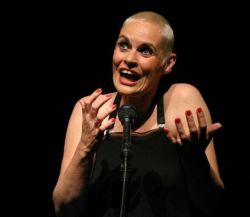

Louis Andriessen and Greetje Bijma, Queen Elizabeth Hall, October 2002

Louis Andriessen and Greetje Bijma, Queen Elizabeth Hall, October 2002

It was one of the strangest and most invigorating musical encounters of my life. Minimalist compositional giant Louis Andriessen was at the piano, fingers poised, eyes bending round the piano body, watching flexi-singer Greetje Bijma's every move as she shrieked, crooned and twittered her way through parodies of everything from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, to bebop and Berio, while chasing herself round on stage. Madness, for sure, but also curiously majestic.

Handel's Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno, Emmanuelle Haim, Le Concert d'Astree, Barbican, March 2005

If it wasn’t for this astonishing performance five years ago I would have thought by now that it was nigh on impossible to pull off a decent Handel opera all the way through. Something always goes wrong. But not this time. What made this so good was not just the near perfection in casting (including Veronica Cangemi, Ann Hallenberg, Pavol Breslik and Sonia Prina), or the fact of having Haim as conductor, it was the rapport. One got the sense that there was a friendly rivalry bubbling up among these singers that spurred them on to greater and greater technical and emotional depths. As an oratorio, it needed only the lightest of dramatic touches to set it going, and what a firecracker it proved to be once it was set off.

Gerald Barry’s The Bitter of Petra von Kant, English National Opera, September 2005

I've never craved a new work like I have The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant after my first experience of it at the ENO, or wanted to hunt down a CD so quickly. Every second of this work fizzes with a deafening excitement and tension. The music is uncompromising, the singing fiendish and the dramatics a hurtling ball of 1970s melodramatic gaseous material. And I’ve never seen a more beautifully designed set in my life.

Andrei Gavrilov’s Goldberg Variations, St John's, Smith Square, May 2006

Andrei Gavrilov’s Goldberg Variations, St John's, Smith Square, May 2006

Never has a concert gone so wrong so right. Gavrilov's recorded Goldbergs are among the finest ever set to disc but personal troubles soon put paid to this bright Gouldian star. He reappeared in Westminster in 2006, a shadow of himself, nervous and sweaty, shuffling on to the stage. The Aria went well. The first variation had a mistake near the end, the second two, three, four, the third a fistful. It was terrifying for him - and for us too. Yet, it was also a miracle. A sublime glimpse to a tradition that has almost completely vanished: the tradition of the genius fumbler. Cortot and Schnabel were never clean but always great. And so too, this night, was Gavrilov.

Ivan Fischer and Budapest Festival Orchestra, Usher Hall, August 2006

Ivan Fischer is a rare thing among conductors: an academic and romantic, a man of ideas and raw passion, Willem Mengelberg and Nikolaus Harnoncourt rolled into one. His visits to Britain with the Budapest Festival Orchestra – the greatest Hungary has had since the time of the Esterhazy’s - have all been unmissibale but one towers above the others: his folkified Rite of Spring at Edinburgh in 2006, both a revelatory and roof-raising experience.

Stefano Landi’s Il Sant’Alessio, William Christie, Les Arts Florissants, Barbican, October 2007

Stefano Landi’s Il Sant’Alessio, William Christie, Les Arts Florissants, Barbican, October 2007

Christie's idea to replicate the all-male first cast of this 17th-century contemplatory oratorio with eight counter-tenors sounded horrifyingly, vaingloriously nuts. In fact it was a stroke of genius, though, to this day, I have no idea how it worked or who was the true genius behind it (though Philippe Jaroussky's ravishing turn in the first act was pretty special). Whatever the case, the third act was a thing of haunting magic.

Messiaen’s Vingts Regards sur L’Enfants Jesus, Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Queen Elizabeth Hall, February 2008

Musically or visually, there are few more awesome sights in the world than Aimard in full sonic flow, his lick of black hair become water, splashing his face this way and that as he slams down another exotic, erotic Messaien squash chord on the grand.

Harrison Birtwistle’s The Minotaur, Royal Opera House, April 2008

It was only with The Minotaur that I realised how beautiful Birtwistle’s music could be, with its oceanic bass hazes and, above, lyrical lines of true wonder. The opera had its moments of bloodied violence of course, its acts of dizzying terror when John Tomlinson and his terrific lunging bull’s head came to horror-filled life. But I will also never forget the serenity of Ariadne (Christine Rice) on Alison Chitty's moonlit beach.

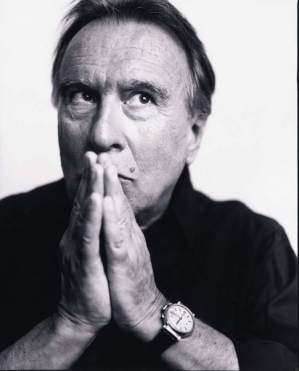

Pierre Boulez, Ensemble InterContemporain, Royal Festival Hall, December 2008

Pierre Boulez, Ensemble InterContemporain, Royal Festival Hall, December 2008

The modernists are still in the lead. Boulez's deliciously complex, delightfully frenetic Derive II (1988-2006) and sur Incises (1996-98), in which the most ravishing French sounds this side of Debussy get sent on a roller-coaster ride for half an hour, still blow all late 20th-century compositional competition out of the water. Their performance last year in Boulez's hands was jaw-dropping, heart-racing stuff.

Riccardo Chailly and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Royal Albert Hall, August 2009

Riccardo Chailly is on fire at the moment. His recent visits with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra over the past two years have been electrifying. I pick out three: a stupendous account of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony last year, a glorious St Matthew Passion in spring 2009 and a Proms visit in the late summer, where we heard Deryck Cooke’s version of Mahler’s unfinished Tenth, which had me reeling.

Igor Toronyi-Lalic's Lows

Andreas Scholl: The Renaissance Muse, Barbican, February 2005

Dunk a counter-tenor in an ill-fitting browny jerkin, scatter frilly pillows on the Barbican stage, add similarly attired lutenist to singer's side and throw soft leaf-patterned green lighting onto their faces, and what you get is the Chernobyl of classical music, a epoch-making aesthetic, moral, philosophical and musical catastrophe so great it is thought that many turned from God as a result.

Anton Safarov's completion of Schubert's unfinished Eighth, Vladimir Jurowski, OAE, Royal Festival Hall, Nov 2007

My, oh, my. Even the composer looked embarrassed by this one. This was a car crash of an idea, and in the car was one of the finest works of Western art music and Safarov had removed this fine passenger's seatbelt and shoved its face through the windscreen.

Simon Rattle, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, 2003+

After the initial hurrah, there hasn't been much to celebrate from what is meant to be the world's greatest musical partnership. Critics in London still hold out a hand of friendship, but in Germany the knives have been out for a few years. I haven't heard one concert by them that has been better than average and many have been far below. Now the only real interest in their output is their recorded legacy, which is, qualitatively, still holding out.

Fiona Shaw’s debut at ENO with Vaughan Williams's Riders to the Sea, November 2008

Two big mistakes here: Fiona Shaw and Vaughan Williams. Shaw's ability to overact and sometimes even over-overact makes most opera singers appear like they're playing poker. So, best keep her away from opera direction, I'd say. Beyond this there's the matter of Vaughan Williams's musical howler: an opera that stank so badly I could barely see the orchestra through the fumes.

Osvaldo Golijov’s Ainadamar, Barbican, April 2008

Ainadamar was a two-and-a-half-hour wail for the death of Communism, told through a cack-handed Lorca poem. I half expected them to offer us free lentil soup and CND badges in the interval. The opera's awfulness is a memento mori for all middle-aged adults, never to presume they know what's going down with the kids, and to remember above all that Marx went out of fashion 30 years ago.

Mikhail Pletnev, Barbican, June 2006

It was obvious something was up when the Barbican doors didn't open. When they did, half an hour after the concert was meant to start, we sat down, then waited a further 10 minutes for the hang-dog Pletnev to walk out onto the stage like a suicidal. He splashed his way through Tchaikovsky's Seasons and Schumann's Kreisleriana like a first-grader and received a standing ovation.

Pekka Kuusisto, Britten Sinfonia, Queen Elizabeth Hall, February 2007

Find me a more irritating violinist than the frolicky Finn Pekka Kuusisto and I will find you a liar. He gurns and scowls and grins and lurches more enthusiastically than your average panto dame. But as with most common criminality, it's not his fault; society is to blame, the musical society that nurtures and encourages this sort of unseemly hyperactivity because it thinks that to ram the place with children, you need children's TV presenters.

Igor and Valery Oistrakh, Barbican, May 2004

"The worst performance of the Bach Double Concerto in D minor I have ever heard outside of school." The words of a very reliable usher.

Mark Padmore’s St John Passion, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Queen Elizabeth Hall, February 2008

In one or two dud concerts in 2008 the invincible shine of the period propagandists suddenly vanished for me. Padmore was attempting to recreate a more authentic conductorless approach to the Bach Passion by shedding a dominating force, sending the soloists (including him) to the back of the orchestra to sing the choruses and chorales together and introducing a cooperative way of getting to the heart of the work. All very nice in principle but pretty appalling in practice. The result was as faltering as Jesus's steps.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment