Cézanne and The Modern, Ashmolean Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Cézanne and The Modern, Ashmolean Museum

Cézanne and The Modern, Ashmolean Museum

French modernist paintings from an exceptional American collection

Has any artist ever painted an apple that gets as close to the essence of appleness as Cézanne? I don’t think so. Cézanne’s apples are the equivalent of William Carlos Williams’s cold, sweet plums. Not only can you almost taste Cézanne’s apples but you can sense their weight, their density. And in your mind, you touch their smooth, waxy skins.

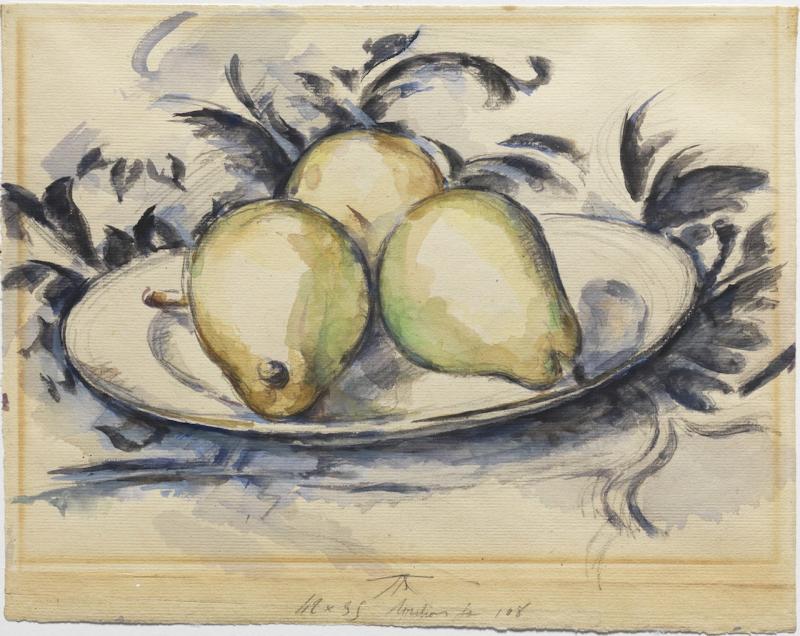

Cézanne’s still-life oil paintings are a thing apart. Those simple table-top arrangements are, for me, the most seductive of anything he ever painted. But of watercolour, that other medium he painted them in, he thought very little. His sketchy watercolour still lifes have, however, their own unsurpassed brilliance. Painted with translucent layers, the objects laid out appear to shimmer and tremble. As he does with his late oils, Cézanne leaves large areas of paper unmarked, making light glow from creamy white surfaces.

A certain claustrophobic, voyeuristic charge gives the painting its arresting power

Sixteen watercolours by Cézanne, as well as oil paintings including those of Mont Sainte-Victoire, the majestic mountain that dominated the artist’s view from his window in Aix-en-Provence and which became an almost obsessive focus for him, are shown together with paintings and sculptures by other, mostly French Post-Impressionist, artists. These works, 49 in total, formed part of the impressive private collection of American businessman Henry Pearlman, who died in 1974. This is the first time the collection has travelled from Princeton University Art Museum – where the works have been on long-term loan since 1976 – to Europe.

Making his fortune from a cold storage company he founded when he was 24, Pearlman became an intermittent collector of minor Italian, French and American realist paintings. Then, rather suddenly, at the age of 50, he discovered the French avant-garde. In 1945, he walked past a Chaim Soutine landscape in the window of a New York auction house, and promptly decided to bid for it. View of Céret, 1921-22, is a wild, rearing landscape, thickly painted – the heavy slabs “slashed on as if by a trowel” as Pearlman later noted – in rich, brooding hues. He went on to buy further Soutine landscapes, the artist’s self-portrait and a rather whimsical portrait of a choir boy, as well as a painting of a hanging chicken carcass, which, with its bottom-up viewpoint, rather reminds one of Degas’ painting of the dangling trapeze artist Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando (National Gallery, London), and with a similar colour scheme too.

The award for most magnificently awkward figure painting must, in fact, go to Degas, whose single presence here is of a nude – the large After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, 1890s – bent over in so improbable a fashion that it’s unclear whether her torso is being supported by a surface or if she’s about to topple head first to the ground. Floating indeterminedly, she could be a cardboard cut-out of slotted-together body parts. Nonetheless, a certain claustrophobic, voyeuristic charge gives the painting its arresting power.

Then there are the two Gauguins – a strikingly ugly wood relief and a rather lovely, tiny terracotta nude; the two Modiglianis; a terrific head portrait by Courbet of his sister; a quietly but deliciously seductive basket of apples and pears by Pissarro, complementing the dish of pears next to it by Cézanne (main picture); a terrifically punchy bronze, Theseus and Minotaur, by Lipchitz; and Van Gogh’s Tarascon Stage Coach, 1888 (pictured above), a gaily colourful but rather rickety stage coach languishing under the merciless glare of a midday sun.

Then there are the two Gauguins – a strikingly ugly wood relief and a rather lovely, tiny terracotta nude; the two Modiglianis; a terrific head portrait by Courbet of his sister; a quietly but deliciously seductive basket of apples and pears by Pissarro, complementing the dish of pears next to it by Cézanne (main picture); a terrifically punchy bronze, Theseus and Minotaur, by Lipchitz; and Van Gogh’s Tarascon Stage Coach, 1888 (pictured above), a gaily colourful but rather rickety stage coach languishing under the merciless glare of a midday sun.

The Van Gogh provides one of the display’s indisputable highlights. But one notes there are no Picassos (and no Cubism) and no Matisses – though Pearlman did buy Matisse’s epic Bathers by a River, 1909, but hastily gave it to a museum in exchange for a more conveniently sized Toulouse-Lautrec, realising he’d be hard-pushed to hang a 13ft by 6ft canvas in either his house or office.

Pearlman’s tastes were modern but conservative-modern. Recognisable genre subjects – still lifes, landscapes, portraits – pleased him best. He’d even painted over the pudenda of one of Gauguin’s relief nudes because it offended him, and was only persuaded to reverse the change by Lipchitz, who claimed it unbalanced the composition. Reading his reminiscences, which are published in the exhibition catalogue, Pearlman doesn’t strike one as a particularly sophisticated connoisseur; more of an enthusiast who relished the excitement of closing a deal on a great work of art. This, then, is a very personal take on "The Modern", but one that is certainly worth taking the time to closely survey. And thank heavens he was that self-proclaimed "Cézanne-worshipper".

- Cézanne and The Modern: Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection at the Ashmolean Museum until 22 June

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment