Crowd Out/Death Actually, Spitalfields Music Summer Festival | reviews, news & interviews

Crowd Out/Death Actually, Spitalfields Music Summer Festival

Crowd Out/Death Actually, Spitalfields Music Summer Festival

Musical street theatre for all and meditations on mortality in London's best melting pot

“I feel so alone I could cry”. As the keynote of Adam Smallbone’s Passion in the breathtaking third series of Rev, that unspoken sentiment provided a passacaglia bass line to the failure of St Saviour’s.

Arnold Circus, the heart of London’s first major housing project now graced by beautiful planting, a ping-pong table and - crucially for the performance - a bandstand in the middle (pictured below with Simon Halsey conducting on the day by James Berry), was the echoing amphitheatre for Pulitzer Prize-winning, New York Bang on a Can composer David Lang’s Crowd Out. Musically co-ordinated by choral supremo Simon Halsey and directed by Thomas Guthrie - more, much more, on him anon - It had two performances yesterday a week after Berlin threw down the gauntlet alongside Simon Rattle conducting Carmina Burana outside the Philharmonie. Crowd Out is the quintessence of what the all-inclusive Spitalfields Music Summer Festival has become all about, and it was moving to tears.

Can I be so sentimental? Yes, because here really were people of all ages, of all religions and none, talking, shouting and singing in a meticulously orchestrated piece of street theatre. It could only have led Rev Smallbone to conclude that, dwindling as the Anglican community no doubt is, the Shoreditch/Spitalfields model of secular communion is a utopian one, the kind of heaven on earth Mozart's Sarastro anticipated. A glorious Midsummer day no doubt helped. The high London plane trees added their rustling notes in the cooling winds, dogs barked, tots on bystanders’ shoulders joined in shouting “HA!” on cue, everybody smiled non-stop or gaped in wonder.

Can I be so sentimental? Yes, because here really were people of all ages, of all religions and none, talking, shouting and singing in a meticulously orchestrated piece of street theatre. It could only have led Rev Smallbone to conclude that, dwindling as the Anglican community no doubt is, the Shoreditch/Spitalfields model of secular communion is a utopian one, the kind of heaven on earth Mozart's Sarastro anticipated. A glorious Midsummer day no doubt helped. The high London plane trees added their rustling notes in the cooling winds, dogs barked, tots on bystanders’ shoulders joined in shouting “HA!” on cue, everybody smiled non-stop or gaped in wonder.

There was a point to all this. Lang, intending 1000 performers but hoping the number will go up to 50,000 to emulate the football stadium songs which were one inspiration, has taken a collection of first-person comments he found on the internet, more about isolation than joining in, and turned them into paradox in the mouths of hundreds. Four “strands” eventually converged on the bandstand from all sides of the Circus, first in normal voices, then antiphonally responding to their megaphoning leaders, taking on staggered melodic phrases set to the words “I feel like rushing into tears”, later adding four more complex patterns. “It ought to end in melody”, said a friend – one oceanic single note perhaps – but that wasn’t the message. We begin alone, we become part of a community, we melt into aloneness again.

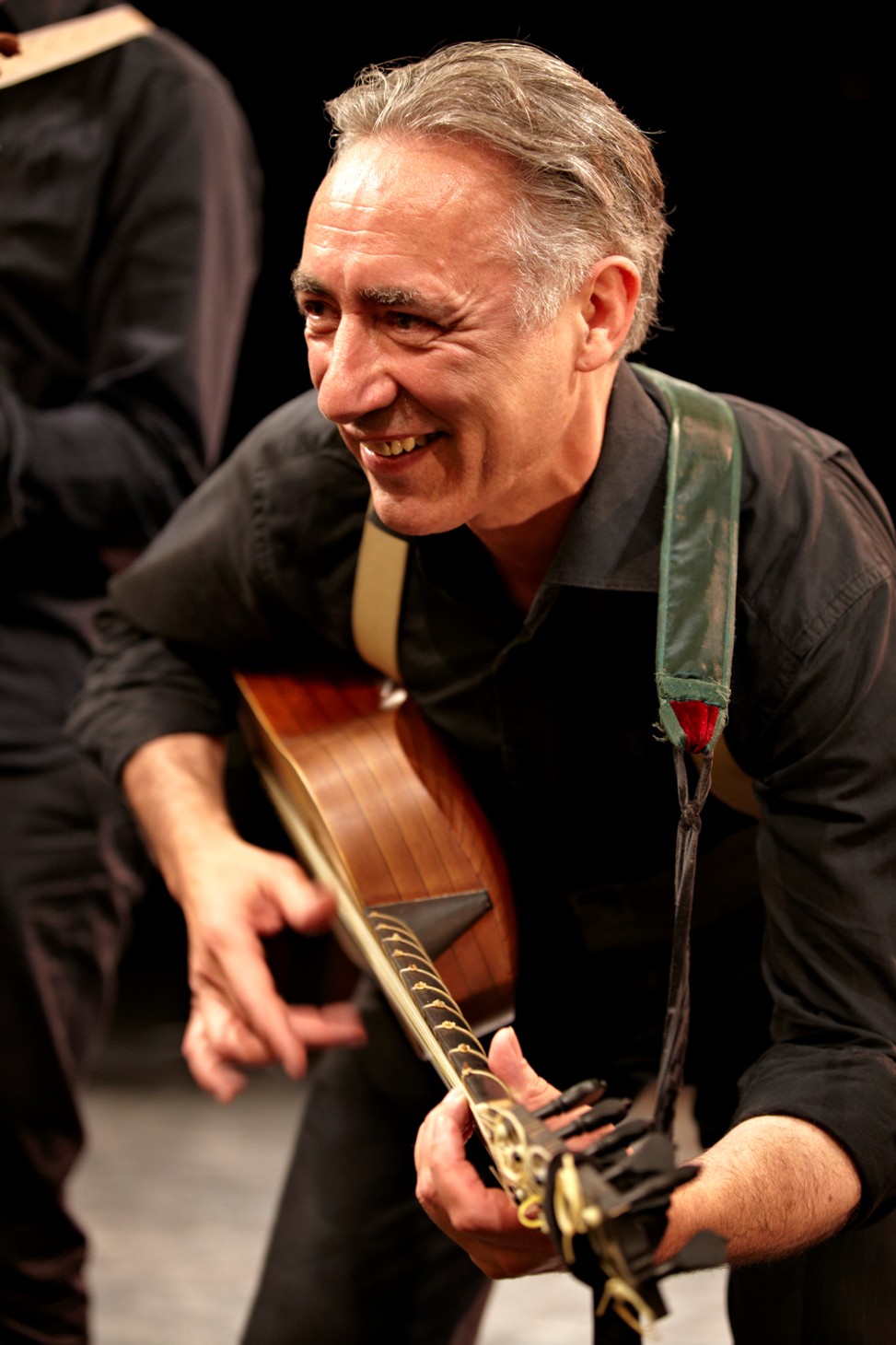

Which brings us to the dread word “death”. It's been much on the minds of those of us absorbed in Poulenc's Dialogues des Carmélites over the past two months – the fear thereof, the possibility of grace. Nothing could have felt more alive than the streets of Spitalfields on the best Midsummer afternoon. And yet that party I stumbled across in one of the historic streets, peopled among others by a splendidly-attired cast of The Wizard of Oz – prize of course to the Tin Man - turned out to be a memorial to a typical denizen, the artist and menagerie-keeper Polly Hope, who died six months ago. Read all about her in Spitalfields Life, the blog by an anonymous “Gentle Author”, which spawned a beautifully produced book and continues with its daily entries, intentionally for the next 10 years. Down at a revelatory venue, Toynbee Studios, another birthplace of social engineering, Bjarte Eike and his Barokksolistene were to wind up a three-part meditation on death with an “Alehouse Wake” (Eike pictured at the "wake" with colleague. Milos Valent. All Death Actually images by Simon Wall)

Which brings us to the dread word “death”. It's been much on the minds of those of us absorbed in Poulenc's Dialogues des Carmélites over the past two months – the fear thereof, the possibility of grace. Nothing could have felt more alive than the streets of Spitalfields on the best Midsummer afternoon. And yet that party I stumbled across in one of the historic streets, peopled among others by a splendidly-attired cast of The Wizard of Oz – prize of course to the Tin Man - turned out to be a memorial to a typical denizen, the artist and menagerie-keeper Polly Hope, who died six months ago. Read all about her in Spitalfields Life, the blog by an anonymous “Gentle Author”, which spawned a beautifully produced book and continues with its daily entries, intentionally for the next 10 years. Down at a revelatory venue, Toynbee Studios, another birthplace of social engineering, Bjarte Eike and his Barokksolistene were to wind up a three-part meditation on death with an “Alehouse Wake” (Eike pictured at the "wake" with colleague. Milos Valent. All Death Actually images by Simon Wall)

I’d not had the chance to experience one of Eike’s celebrated Alehouse raves when I heard him and his phenomenal team as the resident orchestra for Handel's Alcina in Oslo (and it turns out its brilliant star, American soprano Nicole Heaston, soon to be seen in Glyndebourne's La finta giardiniera, was sitting behind me last night). They were the reason I signed up for this final flourish of the Festival. But it was much more than a showcase for the livest-wire fiddling in the business. Renaissance man Tom Guthrie had put together a theatrical triple bill embracing a Schubert song-cycle and Bach motets done at the highest level, all death-devoted.

That dread word, “Tod”, only emerges in the 16th song of Die schöne Müllerin (The Fair Maid of the Mill), and it fairly made the spine tingle on its first appearance. But all was clearly not well from the start with tenor Robert Murray’s suitor – a manic-depressive, at least, stricken by anxiety even at his happiest. The spookiness was heightened by the puppet Murray manipulated (both pictured), more a Doppelgänger than a companion. Given a singer’s inevitably limited skill in puppetry, the figure probably moved as well as it could, though I’ve seen more lifelike headtilts and questioning looks. The main thing was that we visualized the story, the unseen girl and especially the intrusion of the huntsman on the scene as puppet and singer stared, stricken, outwards and upwards.

That dread word, “Tod”, only emerges in the 16th song of Die schöne Müllerin (The Fair Maid of the Mill), and it fairly made the spine tingle on its first appearance. But all was clearly not well from the start with tenor Robert Murray’s suitor – a manic-depressive, at least, stricken by anxiety even at his happiest. The spookiness was heightened by the puppet Murray manipulated (both pictured), more a Doppelgänger than a companion. Given a singer’s inevitably limited skill in puppetry, the figure probably moved as well as it could, though I’ve seen more lifelike headtilts and questioning looks. The main thing was that we visualized the story, the unseen girl and especially the intrusion of the huntsman on the scene as puppet and singer stared, stricken, outwards and upwards.

The real coup was to add to Murray’s infinitely expressive voice, running from slivers of introspection to a heroic vein few English choral-scholar tenors can match, an arrangement of Schubert’s piano part for two guitars, percussion and four strings. How the ensemble underlined the edge of Schubert’s dance tunes, though the majority of the songs were more selectively scored, the limelight belonging to consummate guitarist John Löfving, sometimes in haunting duet with Johannes Lundberg’s jazz/classical double bass pizzicato. The doomed miller-boy's final merge with the ever-present stream floated with supernatural beauty. The performing version, apparently made by Guthrie, who else, could not have been more sensitively or skilfully done.

It’s a golden age for young British tenors, and we heard another of astonishing musicality in the Bach, Samuel Boden. Nothing could have been more pain-easing than his part in the fugue which relieves the dark intensity of Jesu, meine Freude. The eight-part antiphonies of Komm, Jesu, komm pinged off the Toynbee wood and plaster in the hands of the best singers in the business. On the top lines were contrasting sopranos Gillian Keith and Elin Manahan Thomas, while the basses blended with impressive restraint.

It’s a golden age for young British tenors, and we heard another of astonishing musicality in the Bach, Samuel Boden. Nothing could have been more pain-easing than his part in the fugue which relieves the dark intensity of Jesu, meine Freude. The eight-part antiphonies of Komm, Jesu, komm pinged off the Toynbee wood and plaster in the hands of the best singers in the business. On the top lines were contrasting sopranos Gillian Keith and Elin Manahan Thomas, while the basses blended with impressive restraint.

Did the movement add anything, though? Not for me: the sub-Peter Sellars semaphoring and the seemingly random rushing about brought none of the images conjured by the Schubert, and spotlighting seemed fairly arbitrary, too: there was no good reason I could see why some of the singers were in the dark. Guthrie is a singular vocalist, too, but there remained just a degree of self-consciousness in what he did, which was further exposed by his fellow musicians in the wake. On this evidence his real talents are as an arranger and an animateur, a bringer-together of superb artists in a clever context.

His ubiquity in the Alehouse was good enough, though, not to curb our enthusiasm. We’d been invited to take our drinks and move around, but a tart sitter told us to go to the back of the hall if we wanted to jig about. I invited her to stand, but in the end we sat, and wished there were space to dance. The format offers plenty of freedom but has a superbly orchestrated framework guided by the ever-likeable Eike. Among the many improvised touches, those of his wacky colleague Milos Valent were surreally funny.

His ubiquity in the Alehouse was good enough, though, not to curb our enthusiasm. We’d been invited to take our drinks and move around, but a tart sitter told us to go to the back of the hall if we wanted to jig about. I invited her to stand, but in the end we sat, and wished there were space to dance. The format offers plenty of freedom but has a superbly orchestrated framework guided by the ever-likeable Eike. Among the many improvised touches, those of his wacky colleague Milos Valent were surreally funny.

The star turn, apart from Eike's ineffable and never attention seeking violinistic wizardry, was Steve Player (pictured). He did a kind of hybrid routine to Fredrik Bock’s brilliant flamenco guitar, Iberiana laced into baroque fantasia – “Juan Kelly”, quipped my friend – and later sang and danced, with the kind of liberating hand movements which remind us there's more to Irish folk choreography than arms-straight Riverdance, to the tune of blind Irish tippler harpist, composer and singer Turlogh O'Carolan.

Did the Purcell-pop crossover work? Absolutely, because of the joy and humour with which it was done. We need much more of the Barokksolistene in this country, and there was just a hint that Spitalfields may in future be the place to hear them at greater length. Just one thing - after the wild multicultiness of Shout Out, it was all exclusively northern European blokey: are you telling me there aren't any equally vibrant women fiddlers around to leaven the tasty pudding?

Next page: two short films of the Crowd Out and Alehouse experiences

Henrique Paiva's short takes on the Crowd Out event

An Alehouse trailer from Barokksolistene

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment