Steve McQueen: Ashes, Thomas Dane Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Steve McQueen: Ashes, Thomas Dane Gallery

Steve McQueen: Ashes, Thomas Dane Gallery

A film and a broken column pay tribute to a young innocent with limited horizons

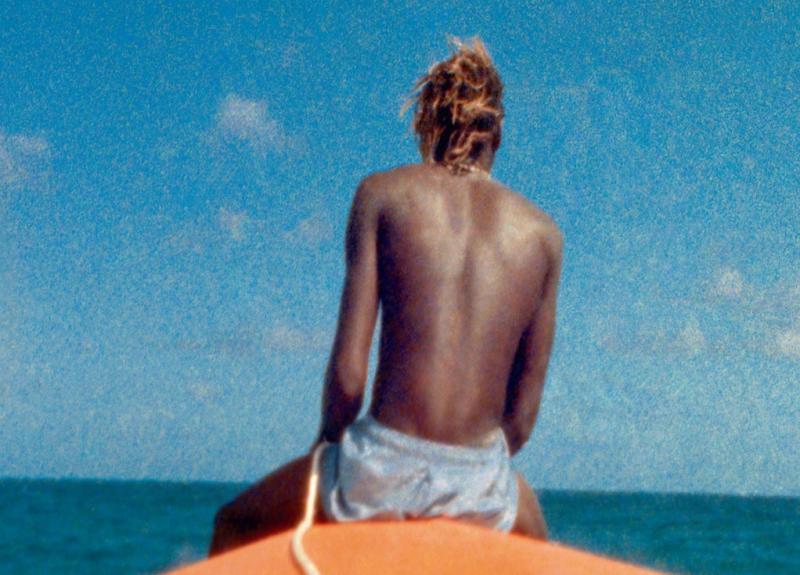

Ashes is a two-part exhibition. The darkened gallery at 3 Duke Street, St James’s is filled with the onscreen image of a young black man sitting on the prow of a small boat with his back to us (main picture). He turns occasionally to smile to camera; he stands up and balances precariously as the boat bobs up and down on the swell; he falls overboard, climbs back on and stands silhouetted against the blue sky, grinning down at us.

With his lithe young body, bleached dreadlocks and disarming smile he seems very amiable and laid back; it's impossible to imagine him in any sort of trouble. And with the bright blue sky, gentle breeze and sound of the waves pounding on the beach, the setting is like paradise, a place where life is easy and time drifts happily by.

But the soundtrack tells a different story. A man recounts how, while out fishing, his friend Ashes found a stash of drugs on the beach of a nearby island and decided to snaffle them. Inevitably, the dealers come looking for him and gun him down; end of story.

Why is this simple tale so arresting? The answer lies in the contrast between, on the one hand, the idyllic setting and the beauty and apparent innocence of the main protagonist (supposedly Ashes, but probably an actor) and, on the other, the brutal reality of the murder. Shot in Grenada, the film juxtaposes the holiday brochure image of the Caribbean as a tourist haven for fun-loving Americans and the view from other side – a lack of opportunity and the fatalism engendered by limited horizons.

Broken Column (pictured) stands resplendent in the gallery at No. 11. Like the many broken columns gracing monuments and Victorian cemeteries, it symbolises a life cut short; rather than being carved from white marble, though, it is cut from black Zimbabwean granite and polished to a high sheen. Instead of a stone plinth, it stands on a wooden pallet, as though it has just been shipped in and will soon be moving on – a mobile memorial to a descendent of someone ripped from their African homeland for transport into slavery.

Broken Column (pictured) stands resplendent in the gallery at No. 11. Like the many broken columns gracing monuments and Victorian cemeteries, it symbolises a life cut short; rather than being carved from white marble, though, it is cut from black Zimbabwean granite and polished to a high sheen. Instead of a stone plinth, it stands on a wooden pallet, as though it has just been shipped in and will soon be moving on – a mobile memorial to a descendent of someone ripped from their African homeland for transport into slavery.

To modern eyes, Victorian gravestones seem irredeemably kitsch; and there’s something fundamentally ridiculous about erecting a marble tombstone to a feckless opportunist, no matter how charming. So is McQueen’s memorial ironic? The answer I suspect is both "yes" and "no". The absurdity of this pompous prick is exactly the point. On the one hand, it is a (serious) memorial to all those whose lives are blighted by poor prospects while, on the other, it asks us to question whom we deem worthy of commemoration and why.

As someone who has been showered with honours – McQueen is the recipient of an OBE and a CBE, not to mention the awards his films Hunger, Shame and 12 Years a Slave have won – it would not be surprising if questions like these were on his mind.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment