Sci-Fi Week: Scoring the Impossible | reviews, news & interviews

Sci-Fi Week: Scoring the Impossible

Sci-Fi Week: Scoring the Impossible

How can music express the unimaginable?

Classical composers have always enjoyed depicting the implausible. Operas based on mythological subjects abound, creating near-impossible staging demands. Musical works based on science fiction are far rarer. Haydn's plodding opera Life on the Moon isn't one of his most scintillating works.

In terms of instrumental music, Gustav Holst's The Planets was actually inspired by astrology, not science fiction. This underrated, overplayed work is far smarter and more original than its detractors would claim, and many of Holst's imaginative touches have been filched by film composers. Play Mars to the average nine-year-old and they'll probably think it's come from John Williams' Star Wars score; it's thanks to Holst that thunderous low brass and repetitive drum beats have become synonymous with galactic catastrophe. When The Planets is loud, it's incredibly loud, though much of Holst's seven-movement suite is refined, delicate and restrained. Alas, many film composers mistake high volume for gravitas, Hans Zimmer's bombastic score for Christopher Nolan's Interstellar being a prime example. Williams' space opera soundtracks do still sound terrific despite their obvious borrowings, fizzing with more wit and colour than the increasingly leaden films which they accompany.

Developments in electronics were crucial to the success of two key 1950s soundtracks. The great Bernard Herrmann considered himself a serious concert-hall composer above all else, though only his film work brought him lasting recognition. He scored Robert Wise's The Day The Earth Stood Still in 1951, and his theremin-drenched music retains its eerie power, the instrument's spooky wail cheekily reused by Danny Elfman 40 years later for Tim Burton's Mars Attacks!

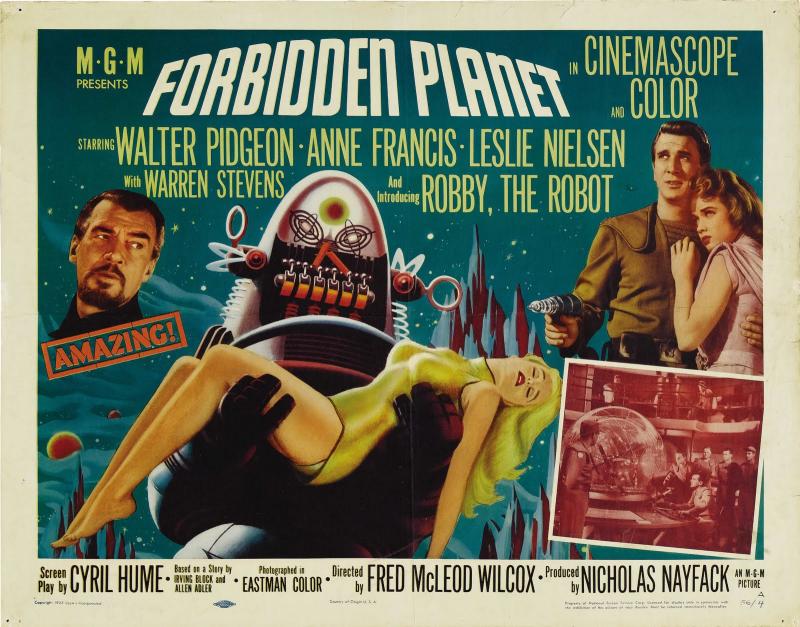

One wishes that Olivier Messiaen had turned his skills to sci-fi; his idiomatic use of a swooning Ondes Martenot making large chunks of his vast Turangalila-Symphonie sound like music from another planet. The most original and endearing sci-fi soundtrack remains the one assembled by husband and wife team Louis and Bebe Barron for MGM's 1954 update of The Tempest, Forbidden Planet. Initially recruited to provide electronic sound effects, the pair were subsequently asked to score the entire film. Due to difficulties with the Musicians Union, the Barrons were credited merely for "electronic tonalities" and were thus ineligible to be considered for an Oscar. Forbidden Planet still sounds fresh, and the realisation that it was achieved through the crudest of means only adds to its charm; Louis generated the sounds by overloading electrical circuits, his wife playing a key role in manipulating and organising the hours of tape.

The most enduring marriage of classical music with science fiction came with Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. Alex North had written the score to Kubrick's Spartacus in 1960 and was an obvious choice when work began on 2001. To North's crushing disappointment, his music was rejected in favour of the temporary classical soundtrack which Kubrick had been using as a stop-gap. Sections of North's score still sound effective, but it's hard not to agree with the director when he later remarked that "however good our best film composers may be, they are not a Beethoven, a Mozart or a Brahms. Why use music which is less good when there is such a multitude of great orchestral music available from the past and from our own time?" North's accompaniment to Kubrick's sunrise can't hold a candle to the opening of Strauss's Also Sprach Zarathustra, and the Hungarian avant-garde composer György Ligeti achieved global fame through Kubrick's dazzling use of his Lux Aeterna. More haunting than either of these is the chilly Adagio drawn from Khachaturian's ballet Gayané, originally written to accompany scenes of carpet-weaving on a Soviet collective farm.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment