Marlene Dumas: The Image as Burden, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Marlene Dumas: The Image as Burden, Tate Modern

Marlene Dumas: The Image as Burden, Tate Modern

A living painter who can compete with Manet and make images relevant to today

"My fatherland is South Africa, my mother tongue is Afrikaans, my surname is French, I don’t speak French. My mother always wanted me to go to Paris. She thought art was French because of Picasso. I thought art was American because of Artforum... I live in Amsterdam and have a Dutch passport. Sometimes I think I’m not a real artist because I’m too half-hearted and I never quite know where I am." (Marlene Dumas)

Marlene Dumas is an artist alright; one of the best. If her paintings weren’t so exceptionally beautiful, this mid-career retrospective would feel overwhelmingly melancholic. This is partly due to the selection. For some reason, the curators have left out her paintings of pregnant women, birth and infants, so shifting the emphasis towards the darker side of life – to alienated sex, power, violence and death.

And let's not forget abuse. In a way, all her pictures are about abuse and the invasion of privacy by the media – the way photographs and film create a false sense of intimacy by bringing strangers close while, at the same time, reducing them to items available for scrutiny.

And let's not forget abuse. In a way, all her pictures are about abuse and the invasion of privacy by the media – the way photographs and film create a false sense of intimacy by bringing strangers close while, at the same time, reducing them to items available for scrutiny.

Dumas works from pictures found in newspapers, magazines, books, postcards and online, and occasionally from photos of herself, her daughter and friends. Whether Africans treated as exotic specimens by Victorian anthropologists, models chosen to exemplify beauty, porn stars inviting you to wank or patients with interesting medical conditions, her subjects have been reduced to cyphers by the prying eye of the lens.

By reconfiguring them in ink on paper or oil on canvas, Dumas doesn’t confer dignity on her subjects or save them from anonymity; instead she investigates the psychological states induced by feeling alienated, displaced, overlooked, misjudged, disregarded or exploited – of not quite knowing who or where you are, or feeling that you belong. It allows one to see her people, to a greater or lesser extent, as self-portraits.

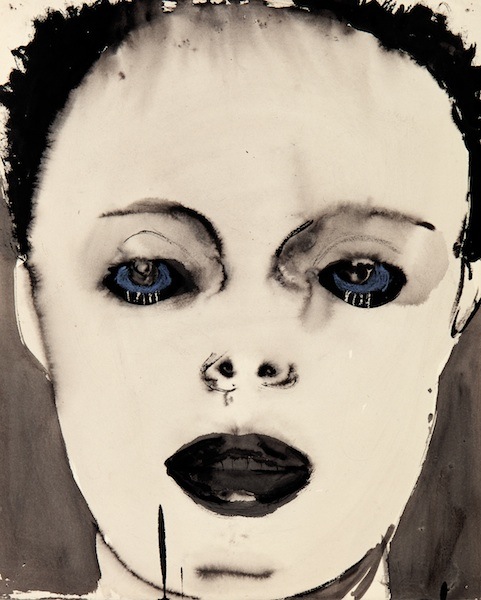

A wall of unsmiling faces confronts you as you enter the gallery; they emerge from the pools, swathes, washes, dabs and veils of watery black ink that give them life, as if gradually coming into focus. Titled Rejects, 1994 (detail pictured above right), they appear to be social misfits – depressed, depraved or suffering deep trauma. Some have been attacked with scissors; eyes and mouths have been scratched or cut away to reveal other features hidden beneath. The faces are masks, actual or metaphoric – protection against real or anticipated violations.

As is so often the case with Dumas’ work, though, the title refers not to the status of her subjects but to the images. Rejected from other projects, the drawings were brought together as an antidote to Models, 1994, portraits of people chosen for their good looks.

A nearby showcase contains a book run over by a car and reduced to pulp; it dates from 1975, the year Dumas graduated from Cape Town University. This poignant object seems emblematic of everything that was to come – evocative images of people battered and bruised by life.

A nearby showcase contains a book run over by a car and reduced to pulp; it dates from 1975, the year Dumas graduated from Cape Town University. This poignant object seems emblematic of everything that was to come – evocative images of people battered and bruised by life.

Arranged chronologically, the exhibition reveals something I have never seen before, especially in an artist this mature (in both respects). Dumas appears to have emerged fully-fledged and, having discovered her subject matter from the off, seems scarcely to have deviated from her path. Her very first paintings, from 1984, are as enigmatic and hauntingly beautiful as the later ones.

One of a series of larger-than-life heads that fill the canvas, Evil Is Banal, 1984 (main picture) is a self-portrait aglow with orange lights. The title doesn’t seem to match the image, though. The only sinister details are the glint in the artist’s eyes and the smudgy grey shadows besmirching her cheeks and right hand, whose foregrounding suggests that Dumas feels guilty about expropriating images of people whose consent was never sought. As she explained at the time: “My people were all shot by a camera, framed, before I painted them. They didn’t know that I’d do this to them. They didn’t know what names I’d call them.”

The White Disease, 1985 captures the pallid face of a patient suffering from a skin complaint. Painted in thin washes of pale green, pink, blue and white, the features appear drained of all vitality. The intimacy of this close encounter with a face we are invited to scrutinise is contradicted by the emotional distance of the sitter who withdraws from the intrusion. The title makes ironic reference to the political unrest frequently referred to in South Africa as “the black problem”.

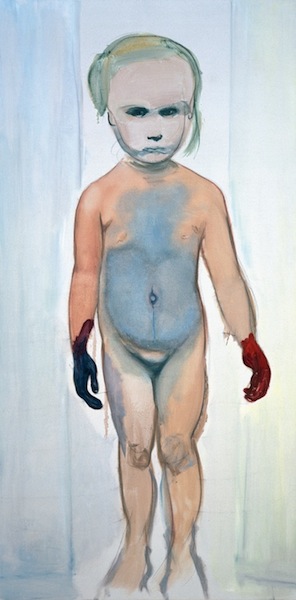

The subject of The Painter, 1994 (pictured above left) similarly meets our gaze with a blank stare, tinged with wary defiance. A naked girl stands in a doorway, her face and stomach smudged with blue, her hands coloured bright magenta and dark purple respectively. She looks sullen, even murderous, but her only crime is to engage wholeheartedly in the act of painting. Her punishment is to be banished from the active to the passive side of the creative act – from artist to model. This glorious picture is a raw yet subtle evocation of the moment Dumas’ young daughter was caught on camera covered in paint; but it is also an allegory of painting itself and the limited role offered women throughout its history.

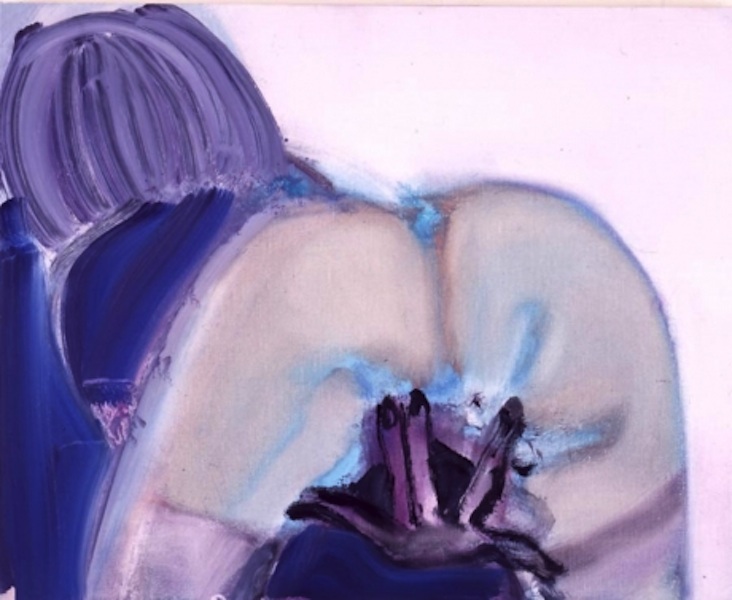

Because the images are culled from porn magazines, sex in Dumas’ paintings is stripped of its erotic charge (pictured left: Fingers, 1999). Death, on the other hand, offers unbridled erotic potential. Her most sublime paintings are close-ups of dead women. Based on a still from the film Psycho of Janet Leigh’s face hitting the floor after she has been stabbed, The Kiss, 2003 looks like a close-up from a love scene. Painted in soft pinks, the lips caress the tiles with a tenderness more suggestive of sexual transport than oblivion. The pose of Lucy, 2004 is based on Caravaggio’s painting The Burial of St Lucy, who was a Sicilian martyr stabbed to death for her faith. Dumas’ heroine throws back her head orgasmically, while the erotic intensity of her abandon is heightened by the hot red paint outlining her nostrils, parted lips and knife wound.

Because the images are culled from porn magazines, sex in Dumas’ paintings is stripped of its erotic charge (pictured left: Fingers, 1999). Death, on the other hand, offers unbridled erotic potential. Her most sublime paintings are close-ups of dead women. Based on a still from the film Psycho of Janet Leigh’s face hitting the floor after she has been stabbed, The Kiss, 2003 looks like a close-up from a love scene. Painted in soft pinks, the lips caress the tiles with a tenderness more suggestive of sexual transport than oblivion. The pose of Lucy, 2004 is based on Caravaggio’s painting The Burial of St Lucy, who was a Sicilian martyr stabbed to death for her faith. Dumas’ heroine throws back her head orgasmically, while the erotic intensity of her abandon is heightened by the hot red paint outlining her nostrils, parted lips and knife wound.

Dead Girl, 2002 (pictured below) is the most shockingly violent painting on display. Based on a magazine clipping from the 1970s of a young terrorist killed while attempting to hijack a plane, this dramatic image is a shameless testimony to the power and beauty of paint and its ability to conjure an image with the utmost economy. An unruly mop of black hair frames the lifeless face, while dark blood congeals around the mouth and nose. Blazes of bright red flow across the dead woman’s blouse like pools of fresh blood, while a heavy band of black anchors the image with a strong vertical.

Dumas’ pictures are as much about conjuring an image from paint or ink as they are about the people they portray; this canvas seems to throw down the gauntlet to Manet and his flamboyant use of black in paintings such as The Dead Toreador, from 1864, and to survive the comparison.

Dumas’ pictures are as much about conjuring an image from paint or ink as they are about the people they portray; this canvas seems to throw down the gauntlet to Manet and his flamboyant use of black in paintings such as The Dead Toreador, from 1864, and to survive the comparison.

Edouard Manet and Marlene Dumas; what a great exhibition that would be. In the meantime, though, revel in this opportunity to see a contemporary painter who, as well as competing with art history, can conjure memorable images that address the present with fluency, subtlety and apparent ease.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Add comment