Connolly, West, BBCSO, Davis, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

Connolly, West, BBCSO, Davis, Barbican

Connolly, West, BBCSO, Davis, Barbican

Masterful Berlioz and the valuable revival of a war requiem. No, not that one...

From the strings’ first entry, sweet and mysterious, conveying at once the erotic charge between Berlioz's Dido and Aeneas, its long-suppressed unfolding and also its transience, the BBC Symphony Orchestra played like a dream for their conductor laureate Sir Andrew Davis.

There followed the death scene for another African queen, Le mort de Cléopâtre, allowing us to hear what Berlioz took from his failed competition entry for the Prix de Rome in 1829 – especially the pulse of the interlude before the final scene, regal and solemn yet burning with regret and shame – and refashioned for Dido’s farewell three decades later. Sarah Connolly made the attempt to give noble form and dignity to Cleopatra’s outpourings of fury at her dishonour, contained at the outset and singing through the line without alighting on each invitation for the kind of proto-Expressionist disruption offered by Berlioz’s word-painting, an attempt compromised more by composer than performer. The language of the piece sits unclassifiably between recitative and arioso, evading a harmonic centre or destination as the set text circles repetitively around the theme of “mes grandeurs opprimés” – my crushed majesty – into which the young Berlioz could already pour embittered heart and soul: I am right, but no one will know it until I am gone.

As much as Berlioz has been a running thread through Davis’s career, so has advocacy of the English choral tradition from Purcell to Colin Matthews and Julian Anderson. Morning Heroes is a now-neglected corner of that tradition, but as he demonstrated in a performance fired with the necessary conviction, well worthy of occasional revival. Sir Arthur Bliss wrote it in 1930 in memory of his brother who fought (as he had) and died at the Somme, “and all other comrades killed in battle”. In the cumulative effect of its texts chosen by the composer as “common to all ages and all times”, the piece might have become a War Requiem, were it not for… War Requiem, Britten's, which elbowed Bliss’s own commission (a setting of The Beatitudes) for the consecration of Coventry Cathedral in 1961 out of the new building and into a nearby theatre.

Morning Heroes is similarly overshadowed, and yet hardly more reliant on the tropes of its time than Britten was on the examples of Mozart and Verdi. Long sections from "Drum-Taps" are trapped into hasty declamation and resort to a pale but shouty imitation of Vaughan Williams setting Whitman in A Sea Symphony. Between them, the long, introverted melodies and sumptuous orchestration of his Li Po setting are worthy of Rachmaninov, even Elgar’s Gerontian musings, but now seem out of proportion to the poem’s embroidery of a blood-stained silk cushion.

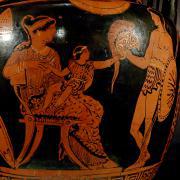

Most personal and affecting were the work’s prologue and epilogue, calling upon Sam West with subtly scored orations of Hector’s Farewell to Andromache (pictured left on an Apulian red-figure column-crater, ca. 370–360 BC), in the patrician tones of Walter Leaf’s translation which Bliss would have known as a schoolboy, and Owen’s Spring Offensive. Owen closes with a rhetorical accusation – “Why speak they not of comrades that went under?” – of such caustic finality that no answer seems possible, yet Bliss supplies it with a choral setting of Robert Nichols’a Dawn on the Somme that, like the excerpt from Chapman’s Homer describing Achilles set fair for war in all his glory, pays ambivalent tribute to the heroism as well as the waste of those thousands who had died around him. The BBC Symphony Chorus excelled themselves in clarity of diction and singing of unflagging vigour. Now batonless but working with a smile like Pierre Boulez, a predecessor of his tenure at the BBCSO, Davis conducted with the understated authority of a man in charge and at home.

Most personal and affecting were the work’s prologue and epilogue, calling upon Sam West with subtly scored orations of Hector’s Farewell to Andromache (pictured left on an Apulian red-figure column-crater, ca. 370–360 BC), in the patrician tones of Walter Leaf’s translation which Bliss would have known as a schoolboy, and Owen’s Spring Offensive. Owen closes with a rhetorical accusation – “Why speak they not of comrades that went under?” – of such caustic finality that no answer seems possible, yet Bliss supplies it with a choral setting of Robert Nichols’a Dawn on the Somme that, like the excerpt from Chapman’s Homer describing Achilles set fair for war in all his glory, pays ambivalent tribute to the heroism as well as the waste of those thousands who had died around him. The BBC Symphony Chorus excelled themselves in clarity of diction and singing of unflagging vigour. Now batonless but working with a smile like Pierre Boulez, a predecessor of his tenure at the BBCSO, Davis conducted with the understated authority of a man in charge and at home.

- Listen here to the concert on the BBC iPlayer until 15 June

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Add comment