Pasolini | reviews, news & interviews

Pasolini

Pasolini

Abel Ferrara’s elliptical take on the last days of the great Italian director

It’s somehow unsettling that, while the physical resemblance between Willem Dafoe and Italian writer and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini is remarkable to the point of being almost uncanny, Abel Ferrara’s Pasolini almost consciously avoids elucidating the character of its hero in any traditional sense.

This is as far away from the usual biopic format as can be. Ferrara’s previous film Welcome to New York may also have hedged certain details on its (purported) subject, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, but that was for completely different reasons. If the French financier-politician and the influential Italian public intellectual may seem an unlikely duo, Ferrara has pointed out that both were risk-takers: Pasolini in his general militancy and the artistic directions he took – we see him here preparing to fight censorship of his last film Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom – as well as in a personal life that led up to his being killed on a beach at Ostia outside Rome on the night of 2 November 1975.

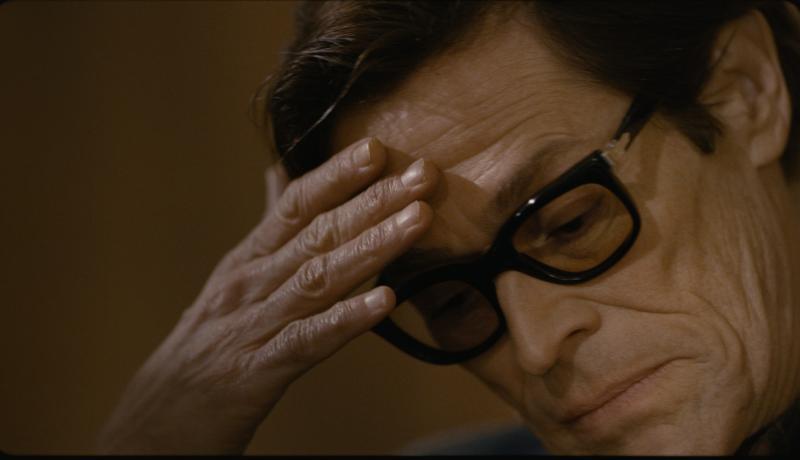

Dafoe even wears a pair of the director’s own heavy glasses

The controversy surrounding that murder remains actual in Italy today, namely whether Pasolini died at the hands of the pick-up he’d brought there for sex, or whether his death was connected to some wider political conspiracy. (The beginning of that final journey, pictured below.) Ferrara has since retracted an earlier comment in which he said that he knew exactly who had killed Pasolini – the director said he was misquoted – and provides his own version of the events of that final night, one which, however, doesn’t significantly expand on or alter previous assumptions.

We get an elliptical presentation of the last days of Pasolini’s life, especially its final hours. Ferrara and his screenwriter Maurizio Braucci obviously researched their subject in great detail, speaking to many who knew him, and received the full collaboration of surviving family and friends. In this often cerebral film, Dafoe gives a very finely tooled performance and even wears a pair of the director’s own heavy glasses (main picture), while some of Pasolini’s actors star in Ferrara's film.

The details of this everyday life are closely charted, from the apartment Pasolini shared with his mother Susanna (Adriana Asti, from his early film Accattone, a subtle presence here until a final-scene outpouring of grief), to his interaction with his cousin Graziella, who acted as his secretary, and friends like Salo actress Laura Betti (Maria de Medeiros), who drops in for a family meal in which professional issues inevitably also arise.

The details of this everyday life are closely charted, from the apartment Pasolini shared with his mother Susanna (Adriana Asti, from his early film Accattone, a subtle presence here until a final-scene outpouring of grief), to his interaction with his cousin Graziella, who acted as his secretary, and friends like Salo actress Laura Betti (Maria de Medeiros), who drops in for a family meal in which professional issues inevitably also arise.

Pasolini’s final interview is here too, with a correspondent from La Stampa, in which he rearticulated his attacks on the values of his times, complacency prime among them: it was titled “We’re All in Danger”. The fact that both sides speak in English in that conversation (when neither spoke that language, apparently) is one of the more out-of-place judgments in a film in which language is rather mixed-up: Dafoe speaks largely in somewhat clipped English, with other characters sometimes communicating in Italian (not always subtitled).

Set against that grounding in the quotidian are dramatic fragments adapted from an unfinished piece of fiction Pasolini left behind (“novel” would be stretching it), Petrolio, and episodes from the draft script for what would have been his next film, Porno-Teo-Kolossal. They’re based on details known principally to scholars and aficionados of the director’s work, and we have to take them on trust. Petrolio brings together varied elements loosely drawing on Pasolini’s own life (he wrote to Alberto Moravia of its protagonist, “aside from the similarities of the story to mine, he is repugnant to me”): scenes of sexual profligacy intercut with the political and cultural salons of Rome, combined with a narrative journey into a desert unknown, with echoes of the exotic worlds into which Pasolini’s own films increasingly moved.

Set against that grounding in the quotidian are dramatic fragments adapted from an unfinished piece of fiction Pasolini left behind (“novel” would be stretching it), Petrolio, and episodes from the draft script for what would have been his next film, Porno-Teo-Kolossal. They’re based on details known principally to scholars and aficionados of the director’s work, and we have to take them on trust. Petrolio brings together varied elements loosely drawing on Pasolini’s own life (he wrote to Alberto Moravia of its protagonist, “aside from the similarities of the story to mine, he is repugnant to me”): scenes of sexual profligacy intercut with the political and cultural salons of Rome, combined with a narrative journey into a desert unknown, with echoes of the exotic worlds into which Pasolini’s own films increasingly moved.

There’s something much closer to home, though also fabular, about Porno-Teo-Kolossal, which has an old man, Epifanio, following the star (literally) to the homosexual city of Sodom, where lesbians and gays live in separate worlds, coming together only for an annual day of fertility, a bacchanal also close to other elements in Pasolini’s work (pictured above). It’s a long scene, effectively free-standing, and the personal touch is strong: Pasolini’s frequent collaborator (and former lover) Ninetto Davoli plays the aged Epifanio, escorted on his journey by Riccardo Scamarcio as the real-life, young Ninetto, with whom Pasolini has a final meeting in a Rome tavern before the final journey that takes him to his death.

Even the brief colours of that bacchanal seem rather muted, and Pasolini is generally a sombrely tinted, even dark film, shot with a kind of non-emotive precision by Stefano Falivene. “Narrative art, as you all know, is dead,” we hear Pasolini proclaim at one stage, and Ferrara has certainly taken that adage to heart, leaving his film to grow on the viewer incrementally. When, rarely, he introduces music, it takes us to a different, somehow more elemental level. There’s Bach behind some beautifully atmospheric shots of Rome early on, while the long closing scenes play out majestically to Rossini’s “Una voce poco fa”, in the rendition, of course, of Callas.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Pasolini

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Add comment