Return to Larkinland was the second of AN Wilson’s intimate portraits of poets, following his similar excursion to “Betjemanland” last year. His very particular form of exploration of the biographical genre results in a selectively detailed portrait seen through the eyes of an admitted admirer, a sense of character created through a pronounced feel for Larkin’s times, caught in redolent black and white archive, as well as in the attention he pays to the places and spaces of the poet’s life.

Wilson knew Larkin well, but wasn’t reluctant to confront the darker issues that have been associated with him after the posthumous publication of his letters and Andrew Motion’s biography, most notably his misogyny and racism. “Sour, two-faced, two-timing,” were among the charges that Wilson got in at the very beginning, making no attempt to excuse such attitudes; the fact that they were raised by a friend did, however, help us appreciate the full range of contradictions in Larkin’s character.

Jazz sung out gloriously through much of Wilson’s film

There were many. In the same scene as Wilson posited that “Larkinland was not a place to be enjoyed”, we had the presenter swinging his shoulders to the poet’s jazz records in an old pub haunt, and a remembered account from another friend of him dancing with joy to jazz at home in his flat, a full glass of gin in one hand, the other catching the beat of the music. Jazz sung out gloriously through much of Wilson’s film, a necessary corrective to our more usual image of the lugubrious Eeyore-like poet who resisted emotional closeness and dreaded death.

What a convoluted web his series of overlapping relationships were. It’s hard to quarrel much with the verdict of “iron selfishness” cast by his most enduring partner, Monica Jones, whom he met in 1946 in Leicester. The pair must have been quite a contrast: Monica, loud and fun, described as somewhere between a duchess and a pantomime dame, whose first thought on seeing him was, “he looks like a snorer”. That became a triangle when Larkin’s closeness to his Hull library colleague, Maeve Brennan, developed, with Maeve the romantic counterpoint to Monica. Then he took up with his secretary, too. Wilson remembered a meeting late in Larkin’s life, the poet complaining about the usual things – being fat, and deaf – then revealing that Monica, unwell herself, was threatening to come and live with him, so he’d have to look after her. Then he smiled a strange, revealing smile: “But we both want it, we’re both so lonely.”

The details of biography were revealed in their own unpredictable order, just like the discoveries of the archive in Hull where objects relating to Larkin’s personal life are kept: his spectacles, the champagne corks meticulously labelled to commemorate past celebrations; a toy statue of Hitler even, a souvenir of Larkin’s two visits to Germany in the 1930s with his order-loving father. No more “abroad” after that, just annual visits to the seaside with either his widowed mother or Monica, the “little Englandism” that was as much a sentimental bond to landscape and architecture as an attitude.

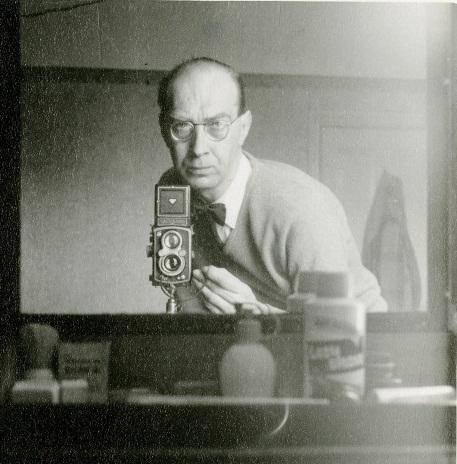

There were surprising revelations, too: an early gay crush on his Oxford room-mate, and the girls’ school stories highly tinged with lesbianism that were his first prose works, evidence of the “passionately sentimental spinster” that lurked in him; how even in his first published schoolboy poem there were the words “high attic windows” that would ring through his later work. We were reminded that the Brynmor Jones library at Hull was as much Larkin’s creation as any of his poems: he oversaw the building’s construction over 15 years, and presided there from a desk he claimed was larger than that of the American president. Rather than anything more intimate its incongruous adornments (Wilson at Larkin’s desk, pictured above) were a photograph of Guy the Gorilla, complete with quotation from Oscar Wilde “the only possible society is oneself”, and a toad figure – actually a frog, Wilson meticulously corrected us – as homage to his two “Toads” poems.

There were surprising revelations, too: an early gay crush on his Oxford room-mate, and the girls’ school stories highly tinged with lesbianism that were his first prose works, evidence of the “passionately sentimental spinster” that lurked in him; how even in his first published schoolboy poem there were the words “high attic windows” that would ring through his later work. We were reminded that the Brynmor Jones library at Hull was as much Larkin’s creation as any of his poems: he oversaw the building’s construction over 15 years, and presided there from a desk he claimed was larger than that of the American president. Rather than anything more intimate its incongruous adornments (Wilson at Larkin’s desk, pictured above) were a photograph of Guy the Gorilla, complete with quotation from Oscar Wilde “the only possible society is oneself”, and a toad figure – actually a frog, Wilson meticulously corrected us – as homage to his two “Toads” poems.

Larkin was Britain’s poet of everyday work, Wilson insisted, and his close reading of “Whitsun Weddings” from Larkin’s notebooks took us through the almost three-year process of that poem's composition, the effort of the couple of hours’ work, post-library, a night that came to seem more attractive for Larkin than the longer-term possibilities and demands of fiction. Wilson was excellent on the sheer process of how writing happens, as he was about faith: how for Larkin, who typically described himself as an “Anglican atheist”, there was no final consolation, unlike Wilson’s own convictions of belief. Which will prove no contradiction, of course, when the memorial in Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey appears on December 2 to mark the 30th anniversary of Larkin’s death.

Director Alastair Laurence has stayed with Wilson from Betjemanland, and their style is very nicely honed. It was built on images gathered from archive (more often, black and white), readings from Larkin’s verse, and the querulous tone of Wilson’s own voice which echoes the poet’s own. “He never showed off,” Kingsley Amis said in the address he gave at his friend’s funeral, saluting an “honesty more total than in any other I have even known”. Or as Wilson put it, he touched out hearts by showing his own.

Add comment