China: Treasures of the Jade Empire, Channel 4 | reviews, news & interviews

China: Treasures of the Jade Empire, Channel 4

China: Treasures of the Jade Empire, Channel 4

The Chinese imperial way of death: burial revelations from Han tombs

Here comes the President, and with him a timely reminder about what the Chinese have been digging up over the past 40 years or so to further demonstrate their exceptional imperial history over the past two millennia.

The story was told by looking at various burial sites created in the imperial attempts to achieve immortality. Modern detective work almost triumphed in its discoveries over the depredations of millennia of tomb-raiders. One of the main thrusts of the narrative was a description of the excavations of a vast network of trenches surrounding the 100-foot-high burial mound, as yet unexcavated, of the Emperor Jing. This site was not very far from the original excavations near Xi’an that startled the world just over 40 years ago, that of the terracotta warriors, six feet tall, who were created to accompany China’s first Emperor, Qin, into the afterlife.

Surrounding the burial mound of the Han Emperor Jing was a fully equipped court in the form of replicas; but the replicas were crowds of eunuchs, some 8,000 at last count, less than two feet high. The courtiers had small penises, with no testicles, and whilst naked were probably clothed in silk which has perished. One such mini-silk costume would have cost as much as the monthly salary of a soldier. These were the earliest known depictions of the court eunuchs who occupied positions of great power (naked figurines from the Han Yang Tomb Museum, pictured above.)

Surrounding the burial mound of the Han Emperor Jing was a fully equipped court in the form of replicas; but the replicas were crowds of eunuchs, some 8,000 at last count, less than two feet high. The courtiers had small penises, with no testicles, and whilst naked were probably clothed in silk which has perished. One such mini-silk costume would have cost as much as the monthly salary of a soldier. These were the earliest known depictions of the court eunuchs who occupied positions of great power (naked figurines from the Han Yang Tomb Museum, pictured above.)

The only complete man allowed into the innermost court would have been the Emperor himself. Concubines were represented too, with miniature coins for the court to spend in the afterlife, as well as miniature seals. It was a total parallel world.

The attempt at “resemblance to life” was complete. There would have been dancers too, for ritual ceremonies and to entertain the court, and hundreds of pots for the kitchen. A thousand terracotta animals too have been found so far: sheep, pigs and dogs. Dogs with their tails up were guard dogs; those with their tails down were pets, or kept for food. Thousands of workers took 30 years to finish his mausoleum. Jing was an autocrat, of course, but popular as he had reduced taxes, and limited mutilations which were a standard punishment. These figures took the place, as did the Emperor Qin’s terracotta soldiers, of what had been the earlier practice of human sacrifice, the ruler’s court dying with him. We assume the populace was grateful.

Xi’an, the capital, we were told, had one million inhabitants, an almost unimaginably huge city. In spite of his wealth, Emperor Jing’s tomb and its ancillary burials of the replicas of the creatures of the court would have come at an almost inconceivable cost. Presumably securing a comfortable afterlife was beyond price: 21st century archaeologists can only be grateful.

Xi’an, the capital, we were told, had one million inhabitants, an almost unimaginably huge city. In spite of his wealth, Emperor Jing’s tomb and its ancillary burials of the replicas of the creatures of the court would have come at an almost inconceivable cost. Presumably securing a comfortable afterlife was beyond price: 21st century archaeologists can only be grateful.

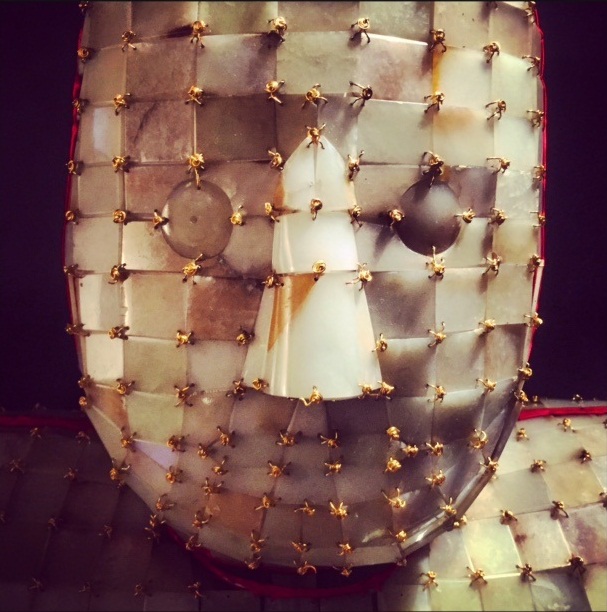

The wealth of the Han Empire – China’s Golden Age – which existed for about 400 years was closely related to silk: there was extraordinary land-based trade with the West as far as the Roman Empire along the fabled Silk Road. Jade was also immensely precious because it was also thought to be a magical material, conducive to immortality, and exclusive to Emperors, buried in suits of plaques of jade, secured with golden nails (jade mummy portrait, pictured above). The excavation of the mausoleum of the King of Chou, a regional ruler during the period of the Eastern Han, indicated that some thousands of pieces of jade would have been attached to the lacquered surface of his burial coffin (main picture). Moreover pieces of precious jade were used to prevent, it was thought, vital essences escaping the body: all orifices of the aristocratic corpse would be so plugged.

The search for ancient China has intensified since those massed crowds of the Emperor Qin’s terracotta warriors turned up in 1974. The palaces have long since disappeared, but the emperors’ and surrogate kings’ determination to live as well in the afterlife as on earth resulted in burial sites which are still in the process of being excavated. The programme suggested that there was one long living legacy, a kind of immortality: the dominance of Han Chinese and the foundation of what is China today. Evidently 90% of China’s current population think of themselves as Han, regarding that dynasty as having formed China’s social and cultural identity.

The last time we saw the Xi’an tombs on television was in Andrew Graham-Dixon’s acclaimed Art of China, when he came within touching-distance of them. Richard Max’s film, though less immediate, was narrated by Paul McGann with subtle drama. Contributions by Chinese and Western archaeologists were interwoven with visual explorations of various sites and brief pantomime re-enactments of Emperors and courtiers in full costume, seasoned by the occasional glimpses into picturesque armies engaged in inevitable warfare. However, the subtitle of the programme, “Secret History”, proved all too apt as so much still remains both mysterious and inexplicable. A few captions to help the viewer visualise the names of emperors and cities, more maps and an occasional time-line would have been very helpful. At times this viewer was baffled as much as enlightened.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Add comment