Arena: Night and Day, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Arena: Night and Day, BBC Four

Arena: Night and Day, BBC Four

Forty years of the BBC's premier arts show marked with rich compendium

Arena is the longest-running arts documentary programme for television at the BBC, and perhaps the world: as the BBC itself phrases it, this compendium celebration presented 24 hours in 90 minutes for 40 years, marking the show's latest anniversary. Conceived by the ever-creative and energetic Humphrey Burton all that while ago, Arena has made over 600 films, looking at high and low culture with equal curiosity, alacrity and even audacity.

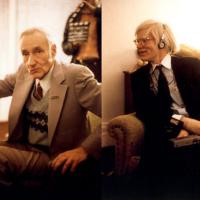

This visual anthology was a slightly queasy trip down memory lane, dizzying and provoking as we heard TS Eliot himself reading The Waste Land to visuals from England’s pub life. “Hurry up, please, it’s time” in that context was genuinely moving, an elegiac phrase which picks up more meaning every time one hears it, and now vanished from popular pub parlance. Contrast came later from New York, with a visit to Andy Warhol’s hangout at Max’s Kansas City bar, completed by the soundtrack of Lou Reed’s “Take a Walk on the Night Side”.

The Ekberg bosom, of whatever age, remained astounding

We covered the world: a cigar factory in Cuba, cue Cuban music; an aged Anita Ekberg followed by photographers, wading into the Trevi fountain, the passage of time underlined by the Ekberg-Mastroanni scene in the same fountain, in black and white, from Fellini’s La Dolce Vita. The Ekberg bosom, of whatever age, remained astounding. How old, though, do you have to be to remember? An amazingly wrinkled and made-up Bette Davis recalled working with a contract player in the 1939 film Dark Victory, an actor called Ronald Reagan. Anything, she sardonically declared, was possible in America.

The conceit was a 24-hour framework, an unacknowledged riff on Christian Marclay’s masterpiece The Clock, itself a literal 24-hour film marking the time minute by minute with film clips showing clocks and watches from hundreds of films. More obviously invoked were several melodious snippets from the great man himself, Frank – Sinatra, that is – singing “Night and Day”.

We opened with a night-time drive through a small Welsh village in the dark hours just before dawn, to Dylan Thomas speaking his poem Under Milk Wood, the little houses as blind as moles; 90 minutes later, we ended the programme in the same village, in the rain, looking out behind our windscreen, the wipers on the glass rhythmically teasing. In between we had Elvis’s cook describing how she finally learned to make fried peanut butter and banana sandwiches just to the singer’s liking; visited Pavarotti, evidently a keen footballer as a youth, watching Juventus on the television with two retired great footballers from that team, his friends; had a black and white glimpse of the Mad Hatter’s tea party from Jonathan Miller’s groundbreaking 1960s television production – to name but a few. Dizzy yet? We hardly had our feet on the ground.

There was just that inescapable whiff of BBC smugness as the very short voice-over introduction told us about acclaimed films and talented directors. Well, yes, but no need to point it out – methinks, you do protest too much – as we were also informed of 9 BAFTAS, and 25 nominations.

There was just that inescapable whiff of BBC smugness as the very short voice-over introduction told us about acclaimed films and talented directors. Well, yes, but no need to point it out – methinks, you do protest too much – as we were also informed of 9 BAFTAS, and 25 nominations.

The range really was huge. There was an early clip of Kenneth Tynan talking to Laurence Olivier about Lilian Baylis, with the great thespian insouciantly quirking his eyebrow as he described Baylis cutting her own salary to help the Old Vic, and subsisting, he thought, on a diet of sausages and sardines. The tone of disdainful astonishment was stupendous. We had several glimpses of Jeffery Bernard, sardonically hilarious in Soho, typing out his column with one finger, after 6 am cigarettes and toast, and later glorifying the thrill of opening-time and lunch, after his mid-morning tumblers of whisky in his flat. Drink lubricates the typewriter, he said, and he probably had only six spasms of job satisfaction a year; he hated what he did.

Woody Guthrie and his folk laments were potent, and he sang his “I Ain’t Got No Home”, as we were shown vintage clips of hundreds, perhaps thousands of homeless Americans living under railway bridges. Poly Styrene, heavily-braced teeth her most prominent feature, told us she had chosen her nom de guerre as pop was a light and disposable product. We followed the Beatles into a fish and chip shop on a magical mystery tour, they and entourage stopping briefly in Taunton, Somerset, with the general populace nearly fainting with amazement. The mesmerising George Melly showed us that Surrealists were almost a fifth column, respectably bourgeois in appearance so that the attackers looked like the attacked.

Roy Plomley figured large, telling us of the Eureka! moment on a cold November evening in 1941 in his digs in Hertfordshire when he thought up Desert Island Discs, and we witnessed some of the interview of its 1,063rd instalment which happened to be with the very handsome young Paul McCartney, being quizzed on whether he was ever lonely. (No, was the answer, he was happy on his own, and anyway he was never short of company.)

Roy Plomley figured large, telling us of the Eureka! moment on a cold November evening in 1941 in his digs in Hertfordshire when he thought up Desert Island Discs, and we witnessed some of the interview of its 1,063rd instalment which happened to be with the very handsome young Paul McCartney, being quizzed on whether he was ever lonely. (No, was the answer, he was happy on his own, and anyway he was never short of company.)

Here were the Rolling Stones, Mick Jagger in particular, being excessively polite to an indigenous Moroccan band, all in gold turbans, with whom the Stones were recording in Tangier, celebrating their 25th anniversary. Those scriptwriters of genius, Alan Simpson and Ray Galton, showed us the kind of prose poetry painfully arrived at for such lines as “that’s very nearly an armful” as Tony Hancock, in the classic “The Blood Donor”, claimed that a prick in the finger was sufficient, and the proposed pint of blood from the arm inconceivable.

Francis Bacon offered us tea or other refreshment in his chaotic studio, Eric Sykes wrapped up his computer in plastic after another long day in the office, and we paid a visit to one of the three conventions per year of the George Formby Society in Blackpool, watching masses of men of all ages plucking the banjo under a screen of vintage film of George Formby plucking the banjo. Jack Nicholson appeared in his dressing-room while making The Shining, and informed us that he always brushed his teeth before work to make it easier on his fellow actors. Peter Blake welcomed a masked and utterly silent Japanese wrestler into his home to pose, and Sister Wendy defined humanity as people who prayed. (Message in a bottle: the Arena logo, above.)

Bewildering, perhaps, but rather wonderful. Trying to make something coherent out of Arena’s omnivorous inclusivity made for a whirligig merry-go-round of a programme in which no cultural pattern was imposed on the past four decades. Still, any 90 minutes which could include TS Eliot and Tony Hancock, Holly Woodlawn and Harold Pinter, Gerald Scarfe and Orson Welles provided subtle lobbying support for the rich eclecticism of the BBC, to be meddled with at your (our) peril.

Arena Gallery: click on first image to begin

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

Add comment