Goya: Visions of Flesh and Blood | reviews, news & interviews

Goya: Visions of Flesh and Blood

Goya: Visions of Flesh and Blood

Behind the artistic life of the great Spanish painter, and the National Gallery exhibition

"Exhibition on Screen" is a logical extension of the recent phenomenon of screenings of live performances of opera and theatre. Initiated with the Leonardo exhibition of 2012 at London’s National Gallery, this is its third season, and the format remains unchanged: a specific show provides the pretext for a bespoke film that goes beyond the gallery walls.

The hook for David Bickerstaff’s film is the unprecedented, one-off exhibition of portraits by the Spanish painter Francisco de Goya (1746-1828) at the National Gallery, London. The viewer both visits the exhibition, and Spain itself, witnessing the geographical settings for Goya’s life and art; eloquent art-historians provide commentary, with copious quotations from Goya’s own letters, too.

His complete deafness after a mysterious illness was devastating

It’s a difficult assignment, as Goya is both very direct and also allusive and elusive. He’s claimed, here and elsewhere, as the first modern artist for his extraordinary sense of the individual, yet is so firmly set in his own social and political time: the Bourbons in Spain, the revolution in France, the Napoleonic wars, the Inquisition – turbulence as the new normality.

Gabriele Finaldi, fresh from Madrid’s Prado to direct the National Gallery, and himself British of Italian heritage, here looks very Spanish – his eyebrows are replicated in many a Goya portrait – and is suitably forthright. He sets the scene by simply stating that Goya’s great curiosity was combined with a piercing intelligence; that he never stopped, never repeated himself. The implication is that this produced portraits of great psychological acuity.

The viewer is led gently through the exhibition – the great familial set-pieces, the aristocrats, his friends, the portraits of his family, and his self-portraits – but it is far more than a guided tour. Scholarly enthusiasts include the exhibition’s curator Xavier Bray, Juliet Wilson-Bareau, and the curators of the Prado and the Spanish royal palaces. We visit a conservator, Joanna Dunn, at the National Gallery in Washington to be told about (and shown) Goya’s orange priming, his glazes, his brushstrokes, his painting wet paint on to wet paint.

The viewer is led gently through the exhibition – the great familial set-pieces, the aristocrats, his friends, the portraits of his family, and his self-portraits – but it is far more than a guided tour. Scholarly enthusiasts include the exhibition’s curator Xavier Bray, Juliet Wilson-Bareau, and the curators of the Prado and the Spanish royal palaces. We visit a conservator, Joanna Dunn, at the National Gallery in Washington to be told about (and shown) Goya’s orange priming, his glazes, his brushstrokes, his painting wet paint on to wet paint.

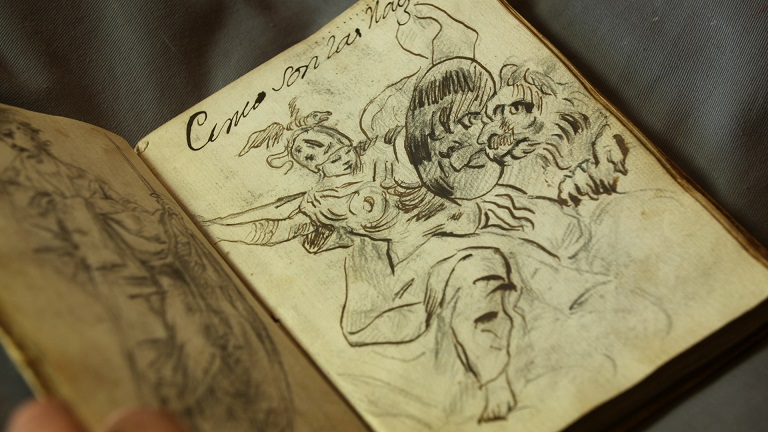

Goya’s 1771 Italian notebook was rediscovered in 1993, and due to its fragility can never be exhibited, but here the Prado’s curator of prints and drawings turns its pages, showing us Goya’s attractive disorder (pictured above). He makes lists of all kinds, including the reigns of the Popes, what implements to use for painting and drawing, bank shares he has bought, the fountains of Rome; he records his wedding date, keeps accounts, notes ideas, and above all sketches from paintings and sculptures and animals from the life that he has observed, fragments to be used in later work, all in a wonderfully untidy tangle exhibiting an omnivorous curiosity and zest. It is a chaos of fact ordered by Goya’s own observations and imagination, the effect as though we were looking over his shoulder.

The chronology is subtle, the biography intertwined with the paintings. We start with the landscape of Aragon, his birthplace in northern Spain, his adolescence spent in Zaragoza, then move with Goya to Madrid. We watch the slow trajectory of his career from designer for the Royal Tapestry Factory making the large-scale paintings of life and leisure which were translated into the great wall hangings, on through his travels to Italy. On his return, his first aristocratic and royal commissions arrived, to decorate cathedrals and chapels with frescoes and paintings (which we see) – and to paint portraits. Goya, perhaps still best known in the Anglophone world as the painter and printmaker of the horrors of war and the Inquisition, was to become the first Court Painter (Madrid's Royal Palace, pictured below right). Over a third of his total oeuvre is portraiture: Goya, we are told, was an intense admirer of Velazquez, and that Spanish genius informed his work.

The whole narrative is unified by the occasional appearance of an astonishing lookalike actor, in simple 18th century dress, over whose ambulatory image – walking, painting and so on – a voice-over in a Spanish accent reads Goya’s own words. The artist was a prolific letter-writer, in particular to his school friend Martin Zapater, for whom he had a passionately loyal affection; his idea of perfection would have been to go hunting with Zapater (Goya was a keen hunter, and profoundly attached to his dogs) and then to drink chocolate.

The whole narrative is unified by the occasional appearance of an astonishing lookalike actor, in simple 18th century dress, over whose ambulatory image – walking, painting and so on – a voice-over in a Spanish accent reads Goya’s own words. The artist was a prolific letter-writer, in particular to his school friend Martin Zapater, for whom he had a passionately loyal affection; his idea of perfection would have been to go hunting with Zapater (Goya was a keen hunter, and profoundly attached to his dogs) and then to drink chocolate.

Goya, we learn, was outgoing, gregarious, and loved music – the film’s background music by Asa Bennett is properly atmospheric – and his complete deafness after a mysterious illness, perhaps caused by lead poisoning from the lead white used in painting, was devastating, although in a way it freed him to do his own work. He was a royalist and a man of the Enlightenment, a man of great friendships and contradictory impulses, who got on wonderfully with the greatest aristocrats of the day, here exemplified by his mesmerising full-length portrait of the Duchess of Alba; she wears two rings, one saying Goya, one Alba, and points to the artist’s name scratched in the earth at her feet.

Whatever debt he may have owed his grandest patrons was repaid beyond imagining for it is through Goya that they are seen and remembered: the Duke of Wellington, almost blank-faced with exhaustion after battle, wearing all his decorations (Goya even added them into the portrait as they continued to be offered); Charles III in hunting mode; Charles IV and his Queen; and the familial portraits of the family and staff of the Infante Don Luis de Borbon, with his wife 32 years his junior, and replete with maid and hairdresser as well as children. Here Goya included himself at his canvas, surely an echo of Velazquez’s self-portrait in his Las Meninas.

Whatever debt he may have owed his grandest patrons was repaid beyond imagining for it is through Goya that they are seen and remembered: the Duke of Wellington, almost blank-faced with exhaustion after battle, wearing all his decorations (Goya even added them into the portrait as they continued to be offered); Charles III in hunting mode; Charles IV and his Queen; and the familial portraits of the family and staff of the Infante Don Luis de Borbon, with his wife 32 years his junior, and replete with maid and hairdresser as well as children. Here Goya included himself at his canvas, surely an echo of Velazquez’s self-portrait in his Las Meninas.

A wealth of information is painlessly imparted: all Goya’s portraits, someone observes, are also self-portraits, the results of conversations even without words, the interactions between a huge spectrum of sitters (and those standing, too) from royals to intellectuals, to friends and family. No-one seems flattered, and all seems convincing. Visions of Flesh and Blood is like the grandest but grandest of television films – with benefits.

- Goya - Visions of Flesh and Blood is released in cinemas nationwide December 1

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment