Seven sides of Alan Rickman | reviews, news & interviews

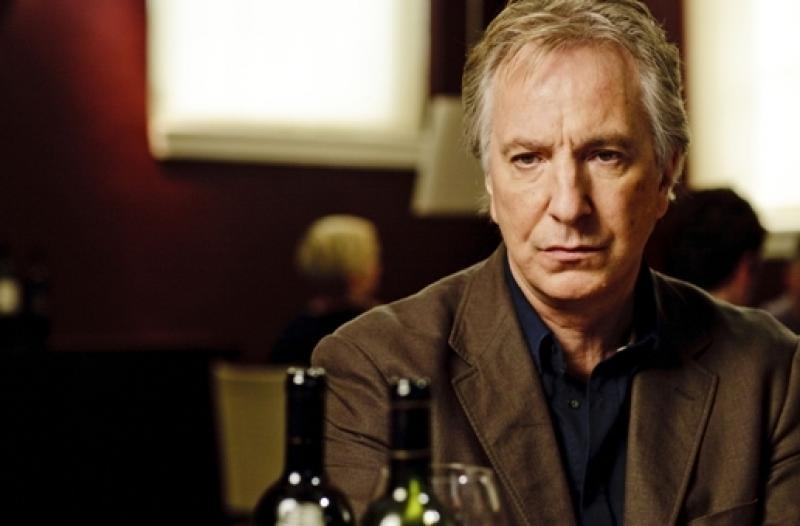

Seven sides of Alan Rickman

Seven sides of Alan Rickman

He was much more than one of the great British villains, as these clips demonstrate

When sorrows come they come not in single spies. It is a bad week to be 69. Hard on the heels of David Bowie's death from cancer comes Alan Rickman's. He was an actor who radiated a sinful allure that first gave theatregoers the hot flushes back in 1985 when he played the Vicomte de Valmont in Christopher Hampton's Les Liaisons Dangereues.

He had a late start as a star. His Hamlet came at the age of 47, followed by an Antony opposite Helen Mirren's Cleopatra at the National which was a rare misfire. But while theatre was his first home, he made the screen his main residence (and, 17 years apart, directed two films himself: The Winter Guest and A Little Chaos). In this video biography we take a look at seven sides of Alan Rickman that fascinated directors and seduced audiences.

Rickman seemed born for a life in the eye of the camera from the moment he embodied the frocked Trollopian hypocrite Rev. Obadiah Slope in The Barchester Chronicles (1982), "the most thoroughly bestial creature". The hooded serpentine eyes, the ripsnorting quiver of the nostrils, the contempt in that lower rack of teeth, they were already all on display here in the pulpit.

In the 1980s British actors acquired a name in Hollywood for giving good villain thanks in very large part to Rickman's turn in Die Hard (1988) as Hans Gruber, a villain so shot through with thrilling dastardliness that he would pull a gun on the man attempting to save his life. His panto turn as the Sheriff of Nottingham in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991) was the comic consequence.

Anthony Mingella's Truly Madly Deeply (1991) is celebrated for Juliet Stevenson's depiction of grief. Revealing a gift for romcom, Rickman played a cellist who after death reappears as a ghost whose deliberately infuriating behaviour persuades her to move on. He's not infuriating in this clip though.

Tim Robbins's political mockumentary Bob Roberts (1992) has never lost its topicality. Robbins played the titular right-wing candidate who expressed his credo through the medium of the country song. Rickman was his sinister campaign manager Lukas Hart III, who wore tinted specs and barely spoke hence the brevity of this nonetheless eloquent quip.

Galaxy Quest (1999) was a loving spoof of sci-fi in which Sigourney Weaver and Rickman both sent themselves up beautifully: she as a ditzy blonde, he as a lapsed Shakespearean actor Alexander Dane better known for his turn as Dr Lazarus, a Spock-like alien in a long-running TV show (based ever so slightly on a certain P. Stewart). In this clip Dane has his regular breakdown as baying nerds await his entrance at a fan convention.

Rickman turned down the part of Lord Farquaad in Shrek in order to play Severus Snape in what turned out to be a long old commitment. Maggie Smith once said that by the end of Harry Potter (2001-11) they both had run out of reaction shots. It was a delicious turn in which Rickman instinctively understood what was expected of him: a pantomime villain halfway between Count Dracula and Larry Grayson.

Rickman's debut as a director was Sharman Macdonald's play The Winter Guest starring Emma Thompson. Having graced her adaptation of Sense and Sensibility (and played her faithless husband in Love, Actually) he was reunited with her in Christopher Reid's The Song of Lunch (2010) to play an old-school sot from publishing, drowning in self-disgust but buoyed up by the hope of one last romantic roll in the hay with a fragrant former flame. Rickman's rare ability to play a thought was never better deployed.

Alan Rickman, 1946-2016

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

A wonderful round-up of the