Des canyons aux étoiles, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Dudamel, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

Des canyons aux étoiles, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Dudamel, Barbican

Des canyons aux étoiles, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Dudamel, Barbican

Nature in Deborah O'Grady's photography outshines Messiaen's homage

Art can inspire music, and vice versa. When concert (as opposed to theatre or film) scores are accompanied by images, however, the effect dilutes the impact of both; above all, the imagination stops working on the visual dimension created in the mind's eye.

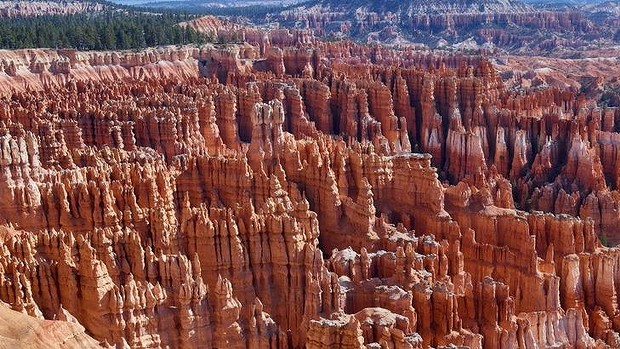

The Messiaenic sound world – and already a limitation is implied in that overused term – deserves its place among the stars: his granitic brass chords, ecstatic strings hovering around a tonic and demented birdsong on wind and piano are like nothing else in the history of music. But as Prokofiev said of Scriabin's harmonic language, they become like a millstone around his neck, preventing real dynamism and motion. When O'Grady suddenly shows us a film of Utah landscape (pictured below) from a speeding car, it's incongruous with the immobility of the music. And her universe is bigger than Messiaen's, embracing environmental ravages and tourism into an ever-expanding picture. Little of this was evident when Messiaen went a-wandering in Utah during the spring of 1972.

It's O'Grady's licence not to illustrate the music literally. Orioles do appear in the second movement, but birds don't always sing on screen when the music does. The most interminable movement, magnificently played like everything else by pianist Joanne Pearce Martin, has Messiaen's epic version of a mockingbird shrieking and plunging; O'Grady insists on perhaps her most beautiful image, a bright green tree rustling against a canyon wall – she travelled to Bryce and Zion Canyons and Cedar Breaks in April – before a slow journey alongside a verdant wood. Birds and animals in nature and in zoos flash crazily around the screen in the synthesis of "Omao, leiothrix, elepala, shama".

The best fusion of image and sound comes in the horn solo of "Interstellar Call" as accompanied by a full moon rising from behind a peak (full moon and ensemble last night pictured below by Keith Sheriff for the Barbican). Paradoxically, the most novel sound in the score actually dates back to 1971. It sounds like Messiaen's biggest step forward after Turangalîla in its extraordinary writing for this instrument, and Los Angeles Philharmonic principal horn Andrew Bain's odyssey – wolf calls, perfect intonation and warming vibrato included – was the stunner of the evening, living up to the promise of his resonant introduction. Unfortunately, his solo developed into a dialogue with a cougher in the balcony and the creaking of leather across the aisle from where I was sitting.

Gustavo Dudamel drew garish-beautiful sounds from his orchestra; as in his work on The Gospel According to the Other Mary, one was aware only of impressive artistic discipline, with none of the flash nor the extremes of tempo which can mar his readings of the great romantic symphonies. This was playing both fierce and luminous, which worked well with O'Grady's work and with Seth Reiser's lighting (singular in making the acoustic panels above the concert platform look like the work of Frank Gehry). Forgive me, though, if I go on to seek out O'Grady's images and not Messiaen's score. There has to be the prospect of her working on a cinema/theatre piece, devised as a unity from the start, with partner John Adams – a composer whose music really does fly through space as Messiaen's, for all its virtues, does not.

- Last concert in the LAP residency, of Mahler's Third Symphony, tonight (24 March - sold out). There is also an open rehearsal with young east London musicians of Copland's Appalachian Spring

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment