It can be given to few commercial galleries to have sustained a relationship with the same artist for over 130 years, but such is the link between The Fine Art Society and James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903).

The FAS was founded in 1876, and is still in its purpose-built original home in New Bond Street. The frontage was designed by EW Godwin, who also designed Whistler’s White House in Chelsea. It has many firsts to its credit, including commissioning Whistler to produce his superbly atmospheric etchings of Venice, which were published by the gallery in 1880. In 1883 Whistler’s monographic print show on the ground floor of the FAS gallery was designed by the artist himself. His etchings, framed and mounted in white, were spaciously hung in a single line against white walls, with yellow furnishings and paintwork. Compared to the conventions then of hanging artwork four or five deep, and strikingly complicated and ornate framing, this was revolutionary, initiated a sensational controversy, and has become the model ever since for solo shows.

He sought to transcend literal renderings in favour of emotional states and moods

Whistler was born in America, spent his childhood in St Petersburg where he studied at the city's Academy of Arts, but lived exclusively in Europe – primarily London and Paris – from the age of 21, from 1855.

He is increasingly understood as one of the most original and greatest artists of the period. Just in the past several decades there has been a plethora of major exhibitions, complete catalogues and biographies. His wit, determination and fearless opinions are memorialised in his The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1890). His character, too, was tantalisingly contradictory: very hard working, a flamboyant dandy, combative, even litigious (the famous lawsuit against John Ruskin, the leading critic of the day who criticised Whistler as a coxcomb), loyal to his mistresses, and finally, after marrying in 1888, an adoring husband: his wife Beatrice, herself an artist, was a former pupil and EW Godwin’s widow. “Whistler’s Mother”, 1871, actually titled Arrangement in Grey and Black No 1, is one of the best-known of all 19th century paintings, has even been a postage stamp in America, although it is actually owned by and shown at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Whistler maintained that no one should care about the identity of the portrait, or indeed of any of his portraits, perhaps an extreme example of art for art’s sake. (Pictured below, The Music Room, 1859.) Hindsight embeds Whistler in his time, yet he was also so far ahead of his historic period. As he wrote, anticipating not only art for art’s sake but some of the rationale for abstraction, “art should be independent of all clap-trap – should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like. All these have no concert with it; and this is why I insist on calling my works ‘arrangements’ and ‘harmonies’.” Yet we do, unavoidably, care about what is portrayed, as well as how. The combative artist signed his prints, drawings and paintings with a butterfly; he was just as much a gadfly. The work and the man are invariably contradictory, which makes his appeal all the more piquant.

Hindsight embeds Whistler in his time, yet he was also so far ahead of his historic period. As he wrote, anticipating not only art for art’s sake but some of the rationale for abstraction, “art should be independent of all clap-trap – should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like. All these have no concert with it; and this is why I insist on calling my works ‘arrangements’ and ‘harmonies’.” Yet we do, unavoidably, care about what is portrayed, as well as how. The combative artist signed his prints, drawings and paintings with a butterfly; he was just as much a gadfly. The work and the man are invariably contradictory, which makes his appeal all the more piquant.

Some 500 etchings, and well over 150 lithographs were produced by this prolific and dedicated artist. They too exemplify his passionate attachment to the new ideas of art for art’s sake. He sought to transcend literal renderings in favour of emotional states and moods, however rooted in their visualisation to his acute observation and superb skill. Subtle as his art was, Whistler was verbally pugnacious and forthright, but paradoxically what is on view here shows his passion for realism as well as for atmosphere, and, contradicting his own complex positions, for emotion. Thus, everything in this marvellous anthology – some fourscore prints from his immense output – is recognisable, and the emphasis is on Whistler’s attachment to the aesthetic possibilities of the varying atmospheres of light, especially that of sky and water at all times of day and night, and how the scenes he focused on were illuminated. He was exceptionally adept at suggesting the intricacies of architecture, particularly elaborately worked façades, and skylines seen across vistas of water.

Some 500 etchings, and well over 150 lithographs were produced by this prolific and dedicated artist. They too exemplify his passionate attachment to the new ideas of art for art’s sake. He sought to transcend literal renderings in favour of emotional states and moods, however rooted in their visualisation to his acute observation and superb skill. Subtle as his art was, Whistler was verbally pugnacious and forthright, but paradoxically what is on view here shows his passion for realism as well as for atmosphere, and, contradicting his own complex positions, for emotion. Thus, everything in this marvellous anthology – some fourscore prints from his immense output – is recognisable, and the emphasis is on Whistler’s attachment to the aesthetic possibilities of the varying atmospheres of light, especially that of sky and water at all times of day and night, and how the scenes he focused on were illuminated. He was exceptionally adept at suggesting the intricacies of architecture, particularly elaborately worked façades, and skylines seen across vistas of water.

His earliest etchings from 1858 shown here are of a journey he made to Paris, the French countryside and the Rhine, published as Twelve Etchings from Nature: here is a dog atop its kennel; a street in Saverne, a town in Alsace, at night, the first of his so-called Nocturnes; a humble kitchen in Alsace, plates on the wall, tiny stove, a peasant woman with her back to us, looking out the window; a very old lady, a rag-picker, seen in profile framed in the doorway of the small room of her workplace, one of several scenes observed in one of the poorest quarters of Paris.

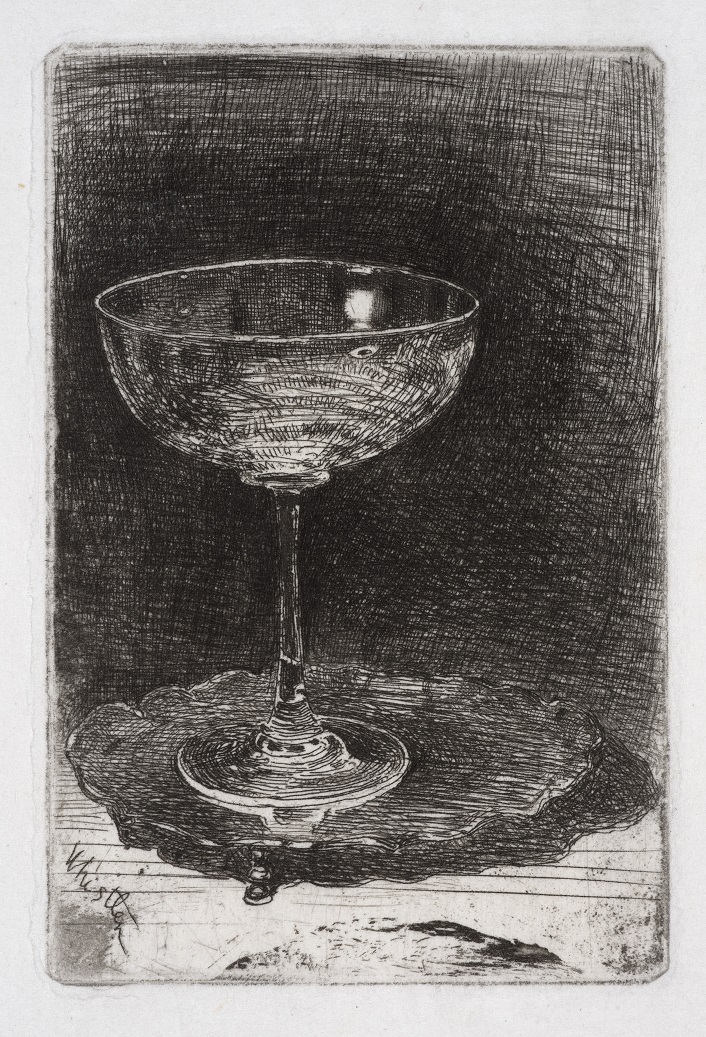

Whistler only made one still-life etching, The Wine Glass (1859, pictured right), a marvel of observation, luminous yet dense, the translucent glass gleaming and reflective against a background of elaborately hatched lines. London and the Thames was a subject he then turned to intermittently for a decade and more, from prints of silvery cloud and water to detailed waterfront scenes, punctuated by boats of all kinds and the buildings on the riverside. The Storm, though, is a scene from the upper Thames, the ferocity of the wind indicated by a figure walking sideways into the pouring rain. There is a clutch of prints of the women in his life, with sensitive portraits of his sister, models, mistresses and wife; and then Venice in all its intricate architecture, winding canals, graceful bridges and the glistening sheets of water separating the great islands. And then in the 1880s on to Amsterdam, its quotidian life, canals and bridges, a poetry extracted from the mundanities of daily life in another beautiful city (Bridge, Amsterdam, 1889, pictured above left).

Whistler only made one still-life etching, The Wine Glass (1859, pictured right), a marvel of observation, luminous yet dense, the translucent glass gleaming and reflective against a background of elaborately hatched lines. London and the Thames was a subject he then turned to intermittently for a decade and more, from prints of silvery cloud and water to detailed waterfront scenes, punctuated by boats of all kinds and the buildings on the riverside. The Storm, though, is a scene from the upper Thames, the ferocity of the wind indicated by a figure walking sideways into the pouring rain. There is a clutch of prints of the women in his life, with sensitive portraits of his sister, models, mistresses and wife; and then Venice in all its intricate architecture, winding canals, graceful bridges and the glistening sheets of water separating the great islands. And then in the 1880s on to Amsterdam, its quotidian life, canals and bridges, a poetry extracted from the mundanities of daily life in another beautiful city (Bridge, Amsterdam, 1889, pictured above left).

The pleasure too of viewing such a fine group of prints is seeing how, on the one hand, with just a handful of lines, as though seizing part of a spider’s web, he can suggest a whole view; and on the other, with intense blocks of ink of varying density, create an atmosphere so palpable we can almost feel it. Sometimes it is one visual idiom or the other, and in some prints both at once, a whisper of lines, an airy drawing, which resolves into a detailed depiction, and inky patches conjuring up the solidity of stone, of buildings and bridges.

Gallery: click on thumb-nails to begin

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment